The SS-Sonderkommando Kulmhof operated the Nazi extermination camp in the village of Kulmhof (today’s Chełmno) to annihilate Jews in the Warthegau region.

Latest Posts

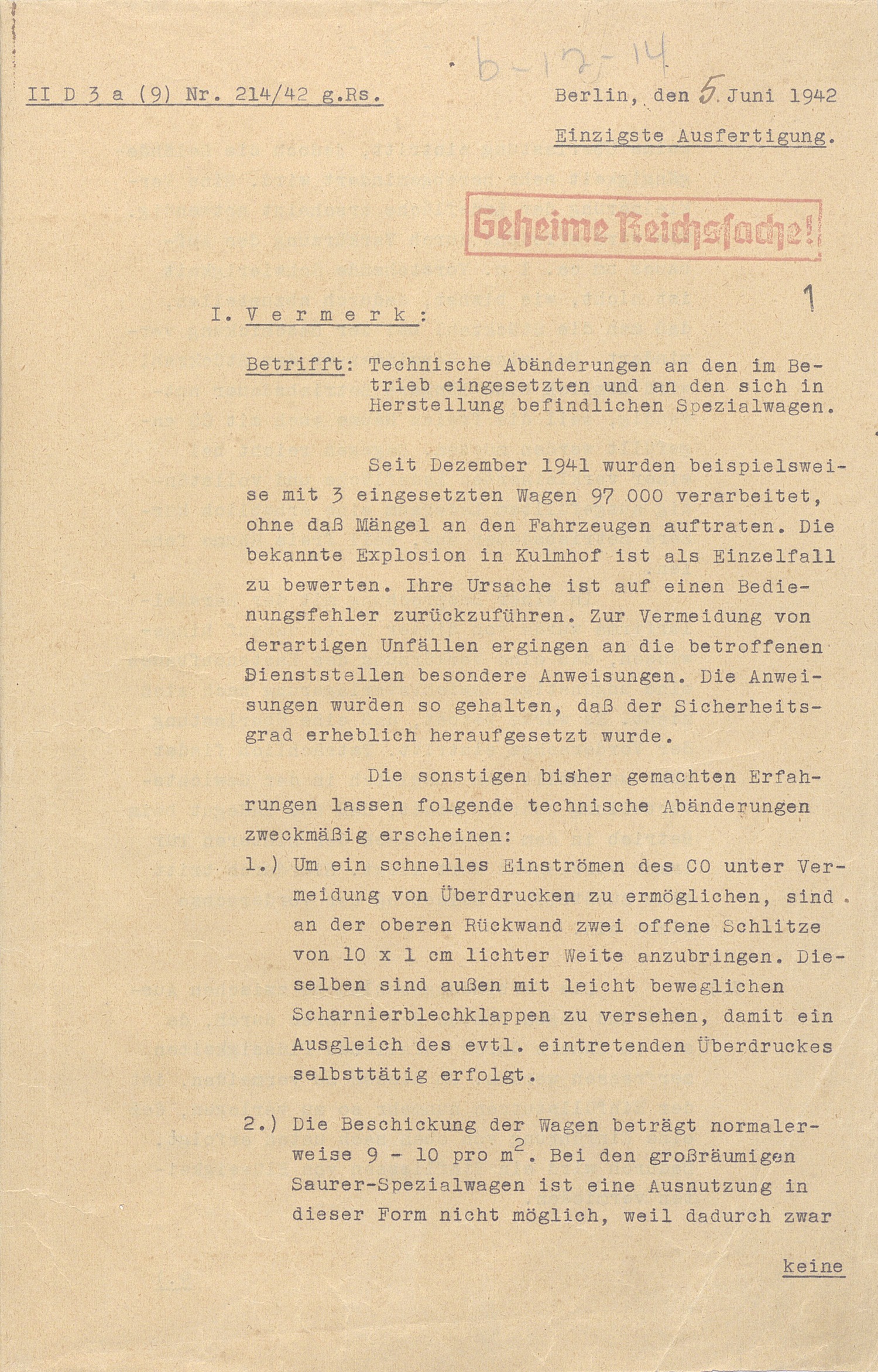

Memo dated June 5, 1942, authored by SS-Hauptsturmführer Willy Just of RSHA office II D 3 a (Motor Vehicle Department

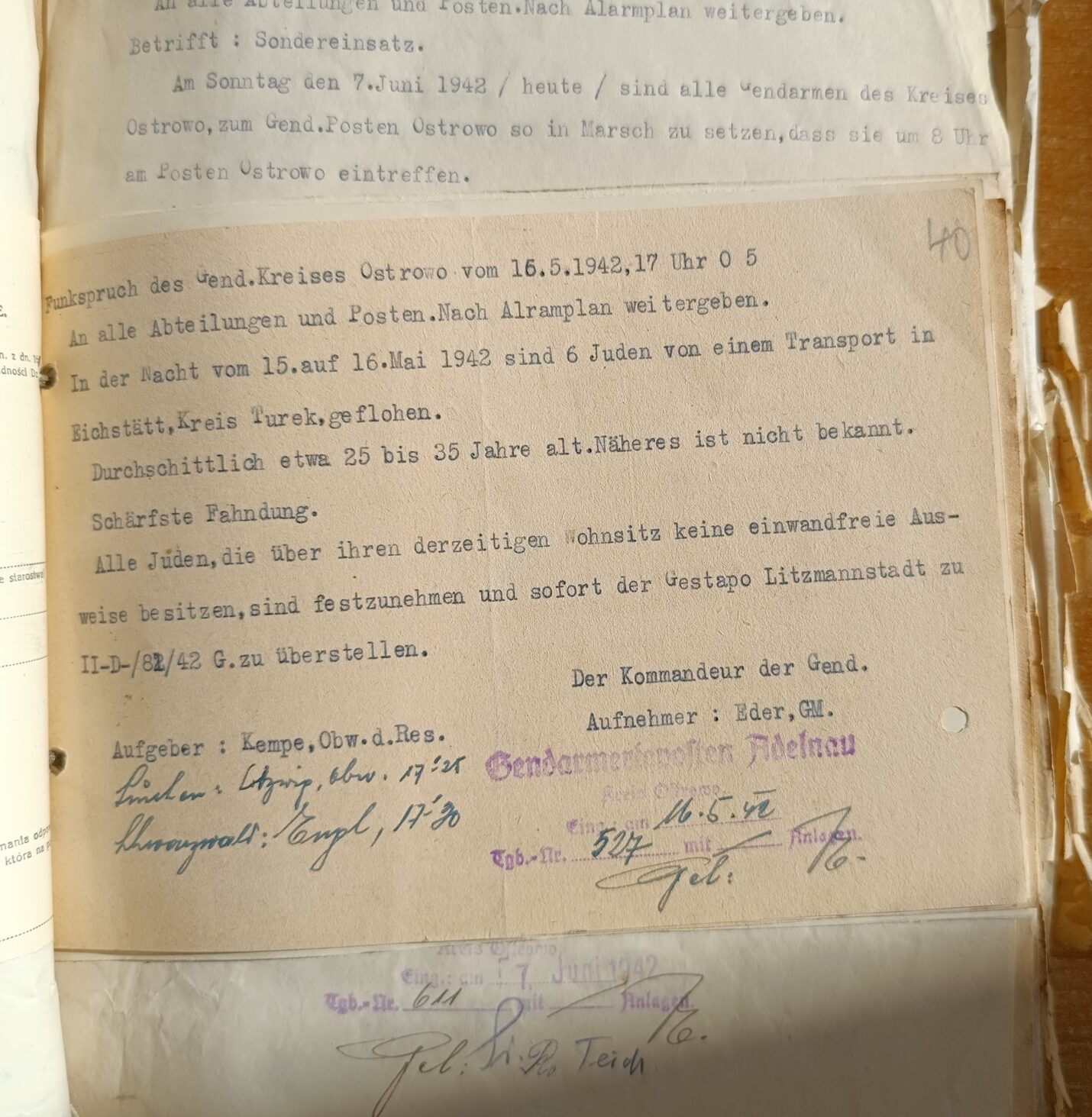

Radio message from the Gendarmerie District Ostrowo to the Gendarmerie post in Adelnau, dated May 16, 1942. The message reported

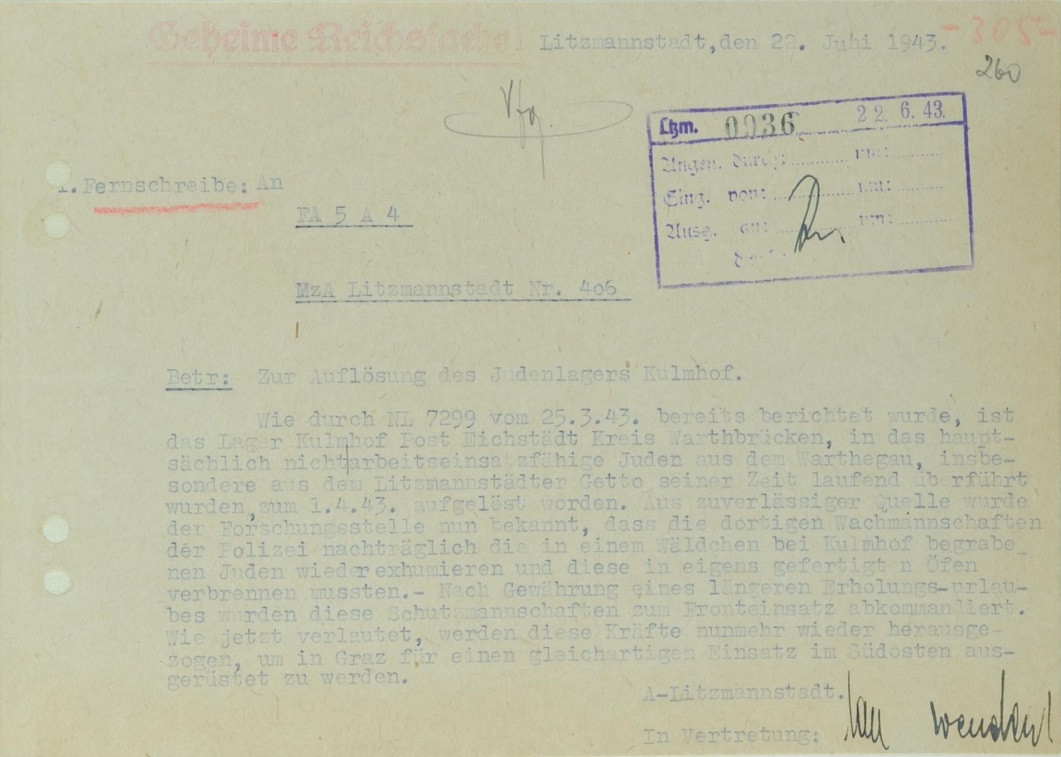

On June 22, 1943, the Forschungsstelle A Litzmannstadt – a local intelligence branch under Hermann Göring's Secret Service –

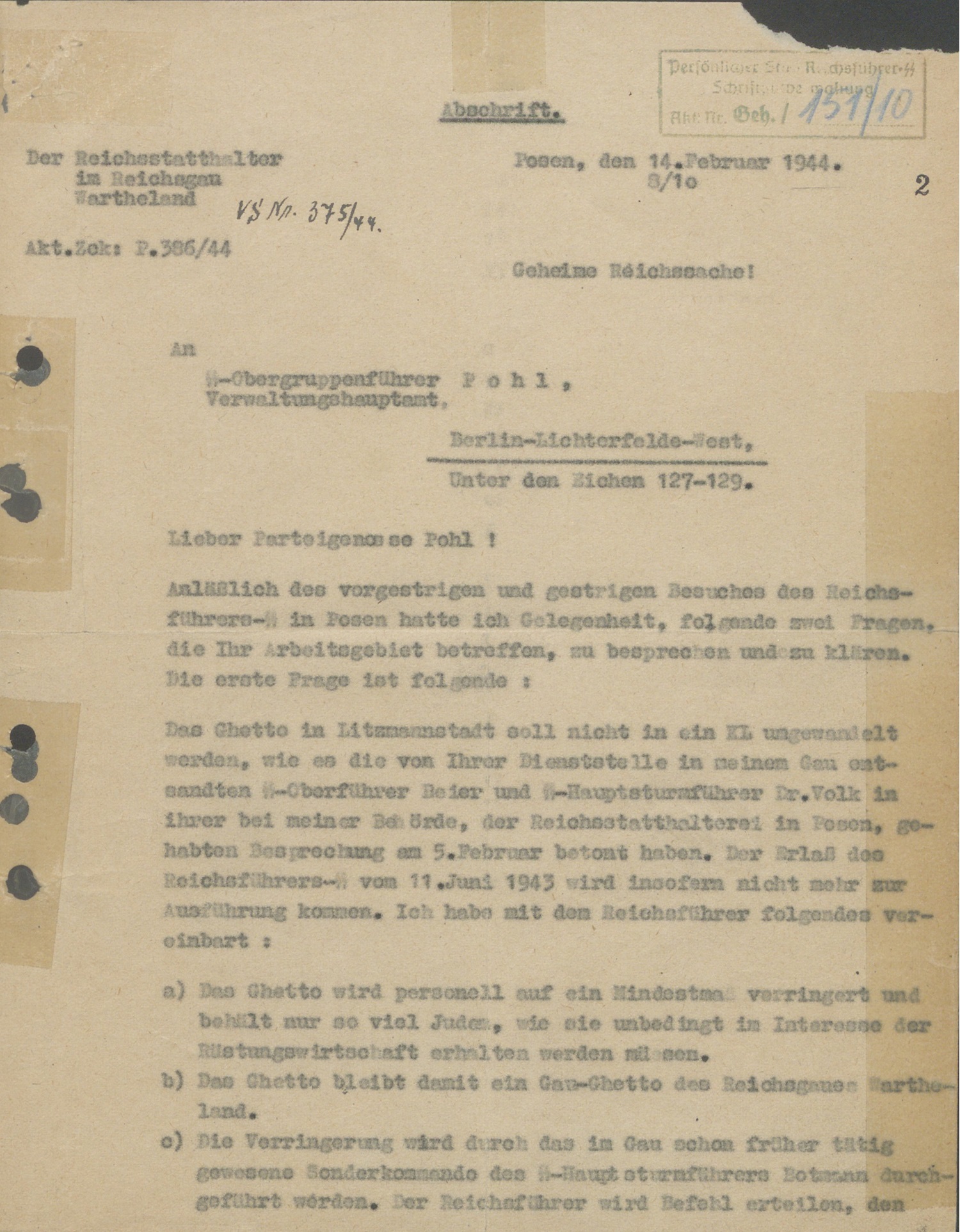

Letter dated February 14, 1944, regarding the Nazi administration's plans for the liquidation of the Litzmannstadt (Łódź) ghetto, one of

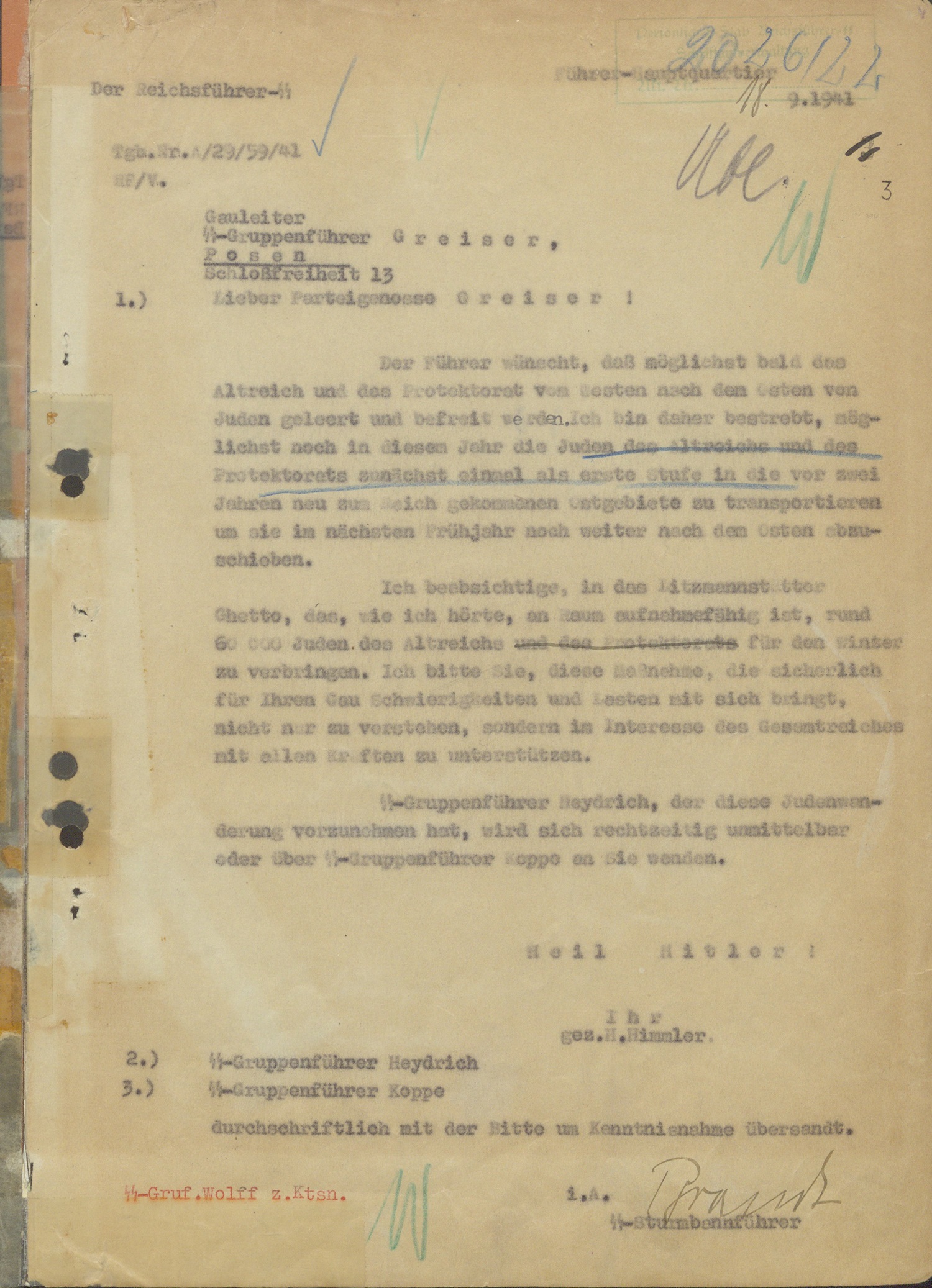

On September 18, 1941, Heinrich Himmler sent a letter to Arthur Greiser, Gauleiter of the Warthegau, conveying Hitler's request that

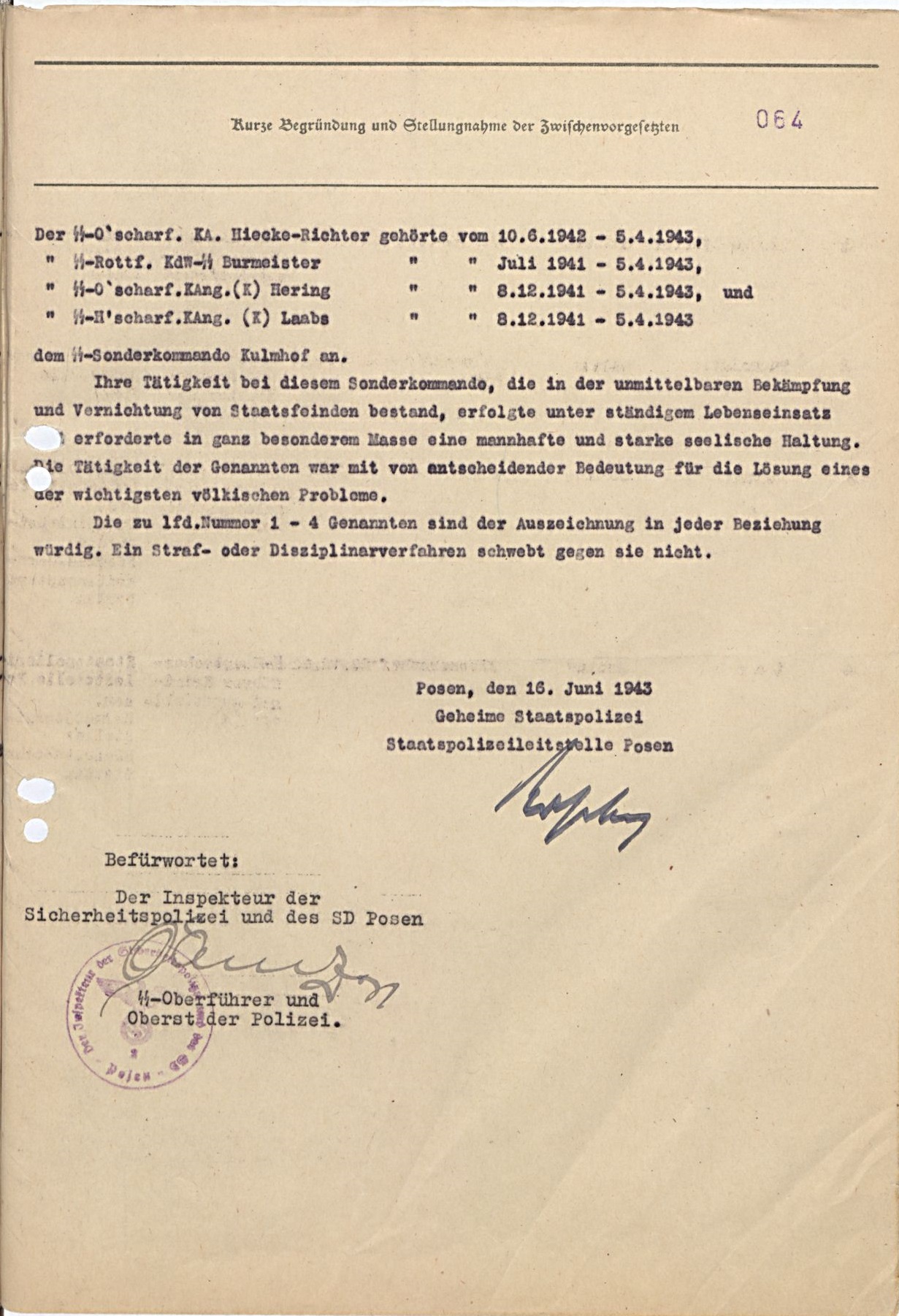

Proposal for the Award of the War Merit Cross II Class with Swords by the Gestapo Headquarters in Posen, dated

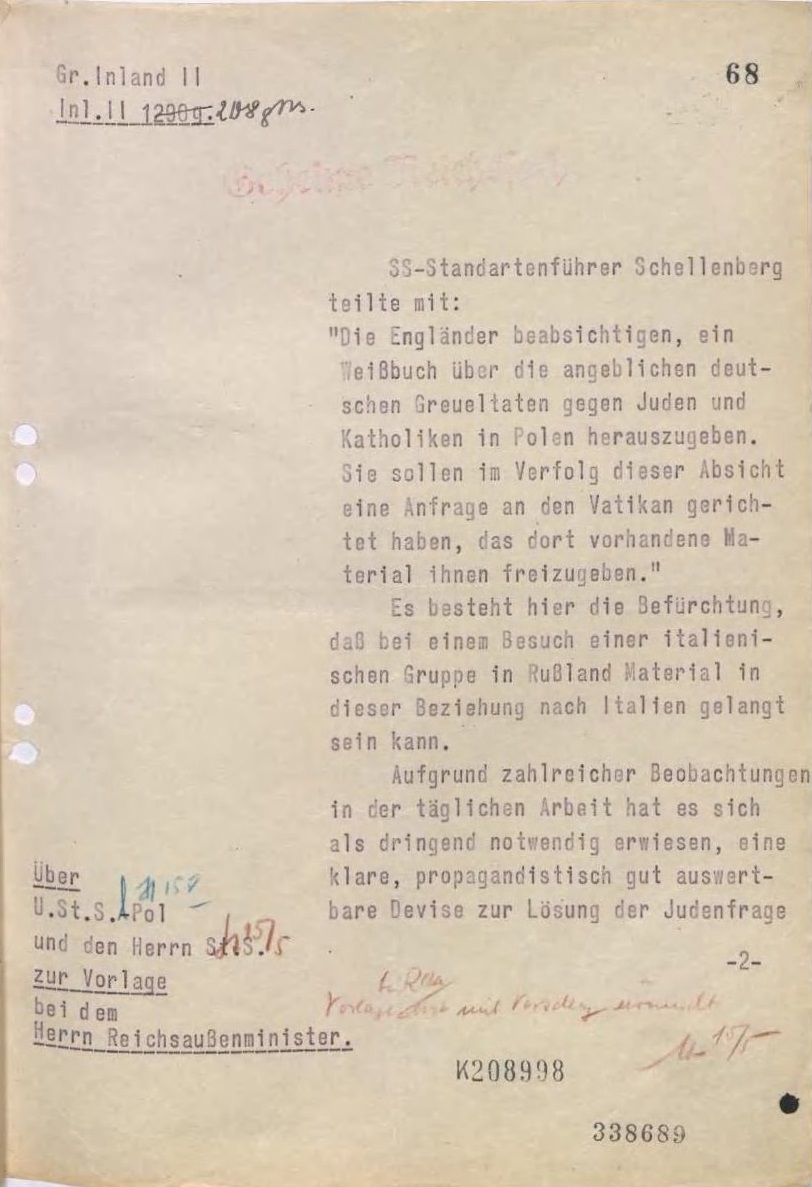

In May 1943, Walter Schellenberg, head of RSHA Office VI (Ausland – SD-Ausland), informed the German Foreign Office of Britain’s

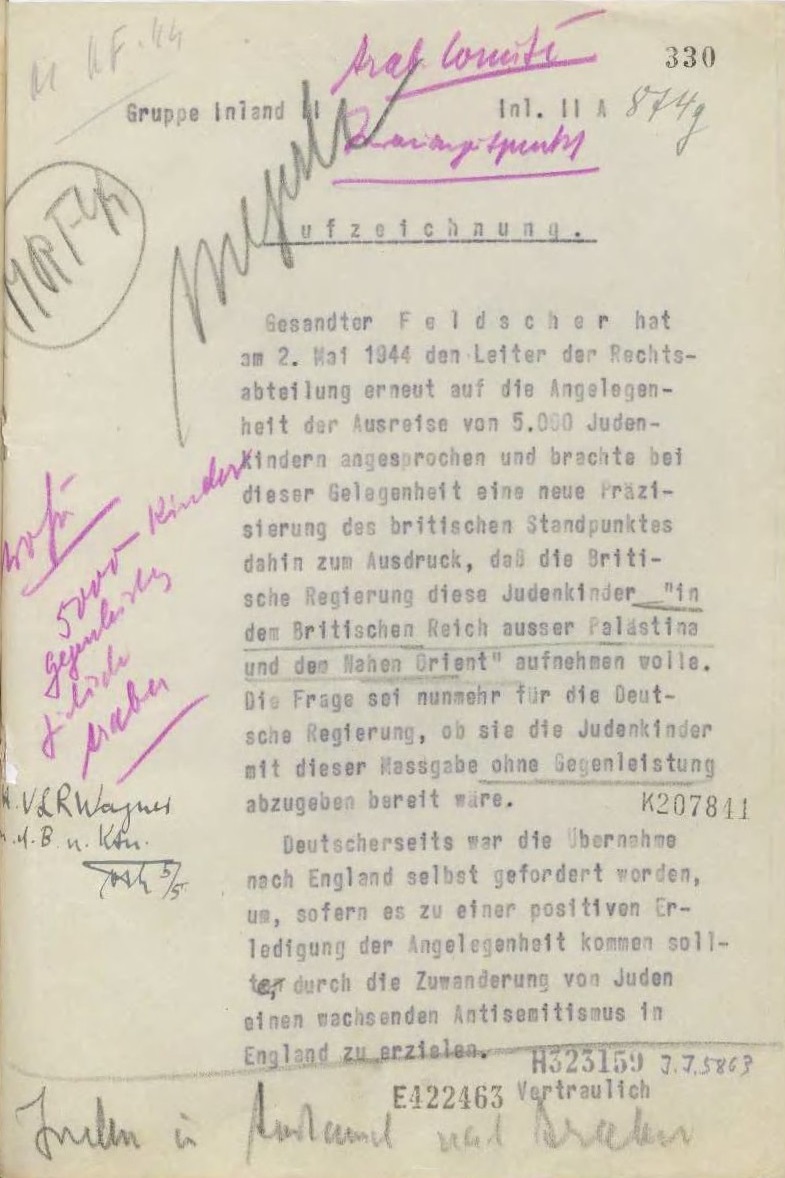

The Feldscher Aktion, named after Swiss diplomat Peter Anton Feldscher, represented a significant diplomatic effort by the British government during

On 8 July 1942, Albert Plate from the Sonderkommando Kulmhof discussed with the Ghetto Lodz Administration regarding the supply of

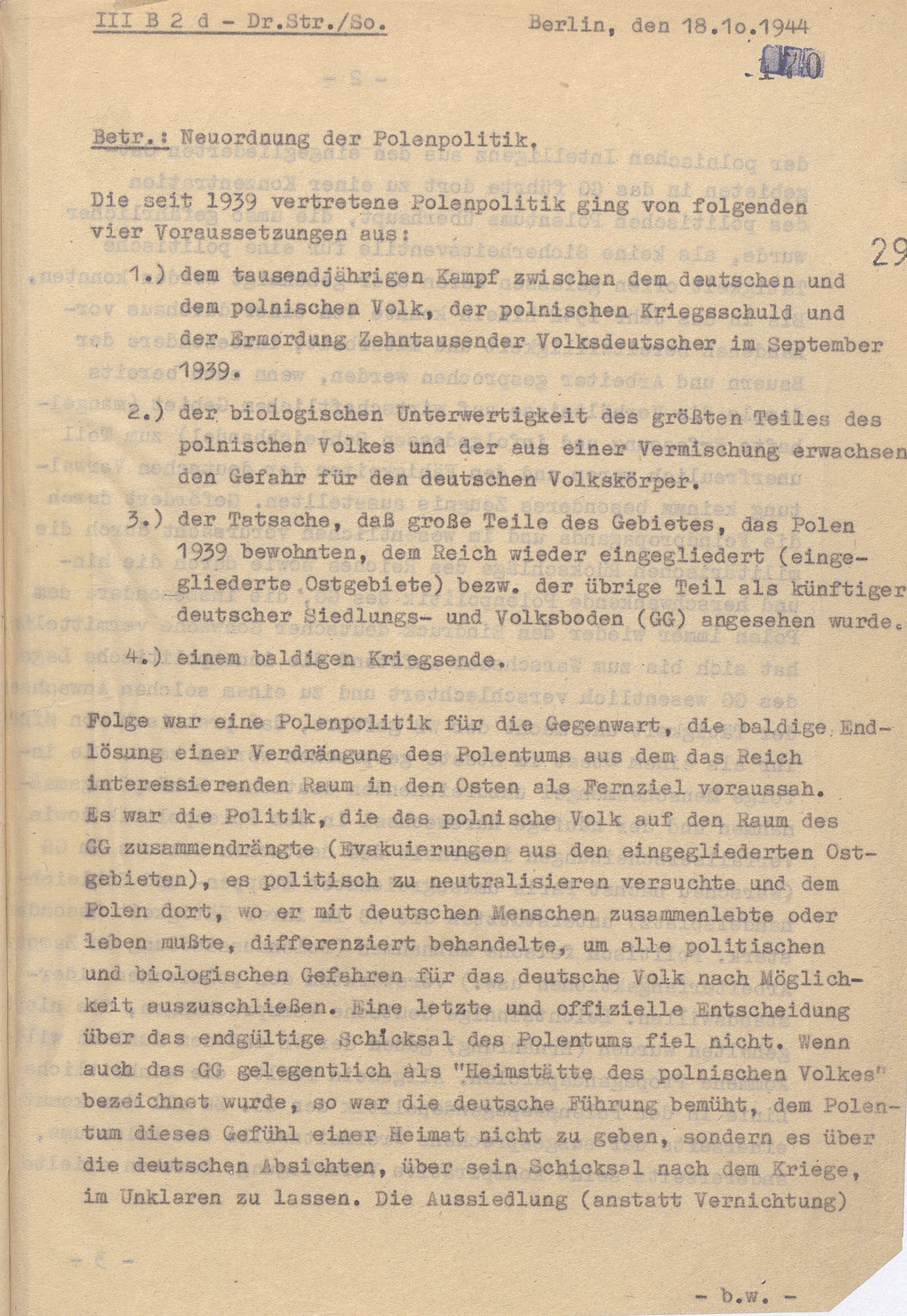

Memo by SS-Sturmbannführer Herbert Strickner, head of RSHA Department III (Volkstum, or Ethnicity), analyzing occupation policy from 1939 to 1944

On April 16, 1943, Hans Biebow, head of the Nazi's Łódź (Litzmannstadt) Ghetto Administration, penned a letter to Friedrich Ribbe

On 15 July 1942, SS-Obersturmbannführer Ernst Fick, commander of the Sennheim training camp, requested a portable flamethrower unit from the

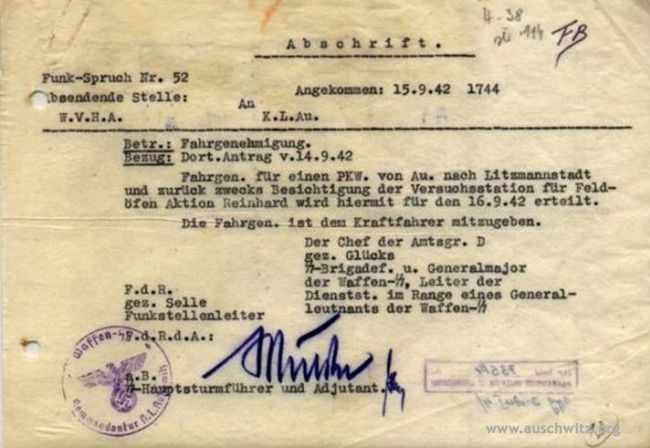

According to a radio message from September 15, 1942 and a trip report dated September 17, 1942, on 16 September

Between 1940 and 1942, Franz Heinrich Bock served as Mayor and Official Commissioner of the Polish village of Poddębice. During

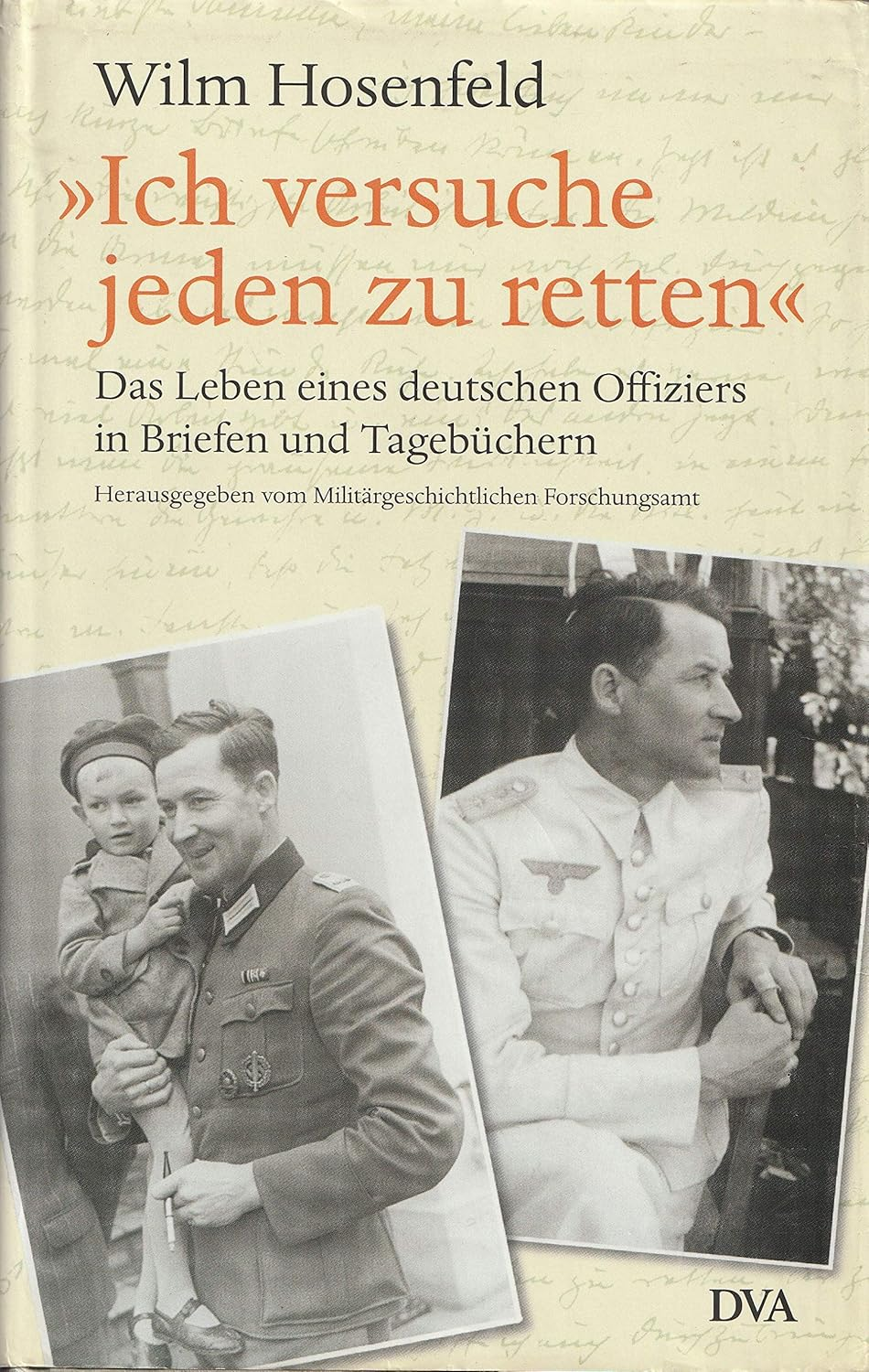

Wilm Hosenfeld, a German officer stationed in Warsaw during World War II, recounts in a diary entry of 23 July

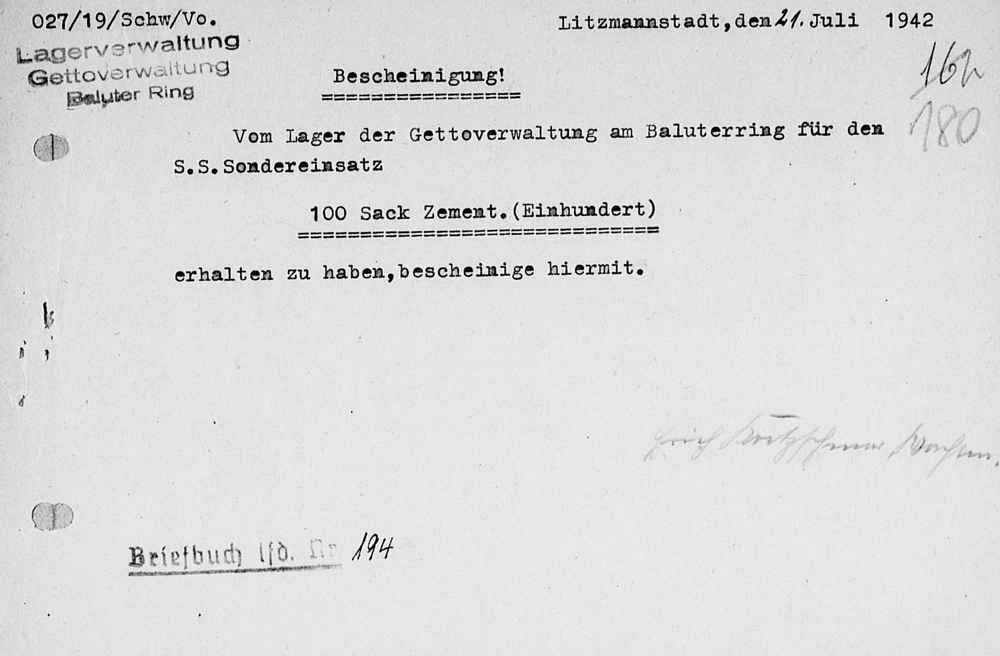

In June and July 1942, the Ghetto Łódź Administration delivered large quantities of chlorinated lime and cement to the

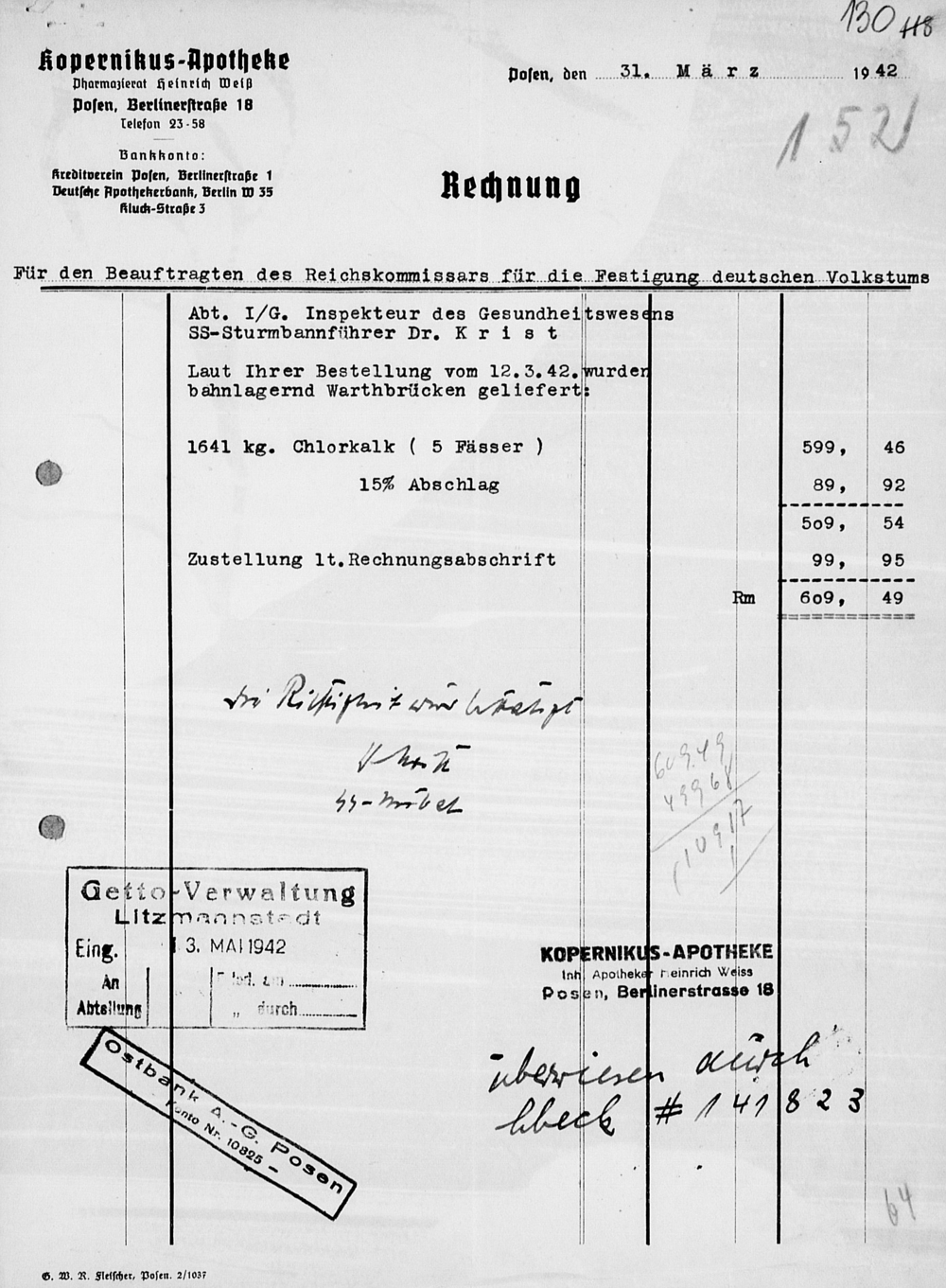

In March 1942, the Inspector of the Health Service under the Reich Commissary for the Consolidation of German Folk ordered

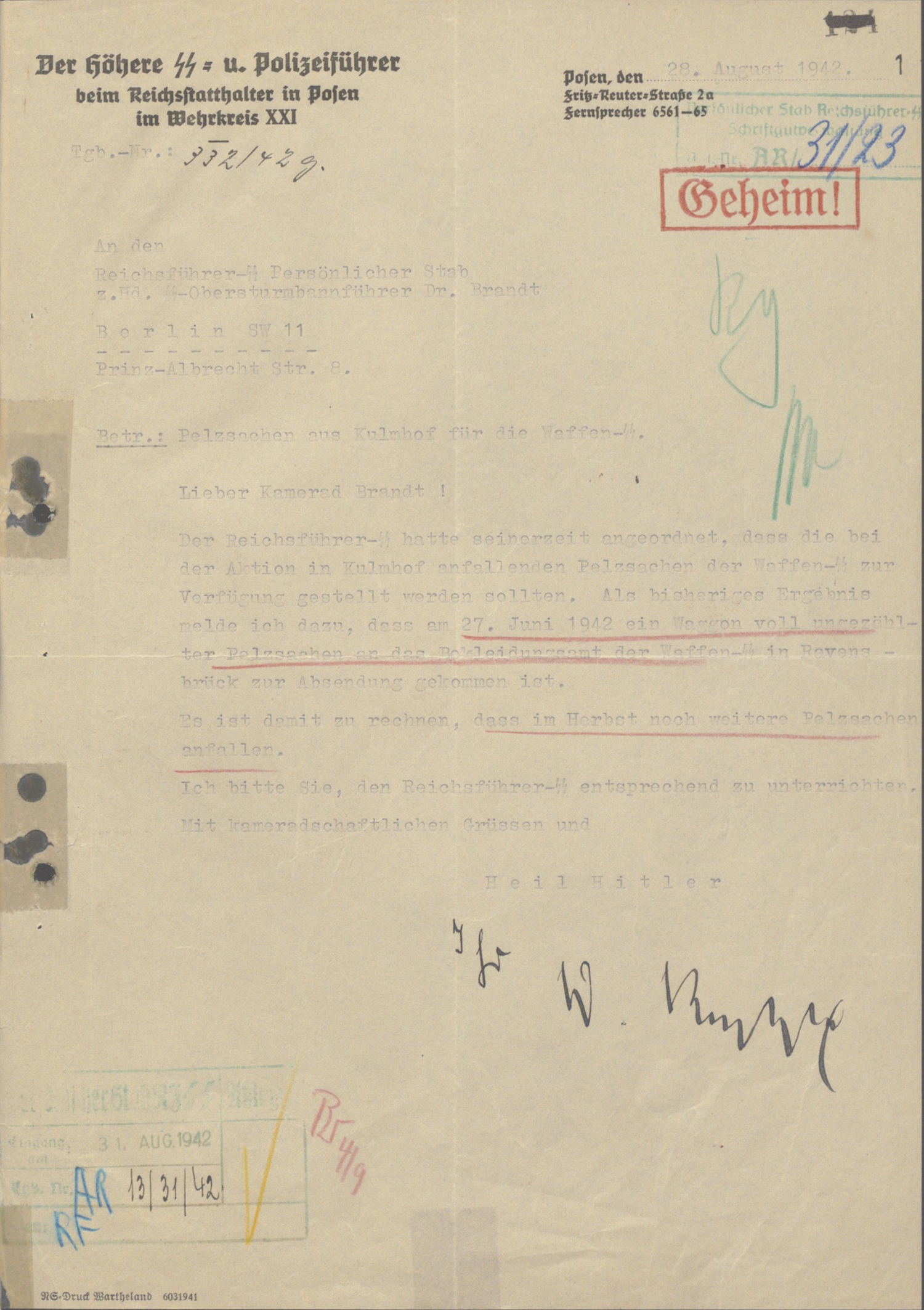

The letter dated 28 August 1942 discusses the transfer of furs confiscated from those murdered in Kulmhof (Chelmno) to the

Deposition in Yiddish in February 1942 in the Warszaw Ghetto by Szlama Winer aka Jakub Grojnowski. In his account titled

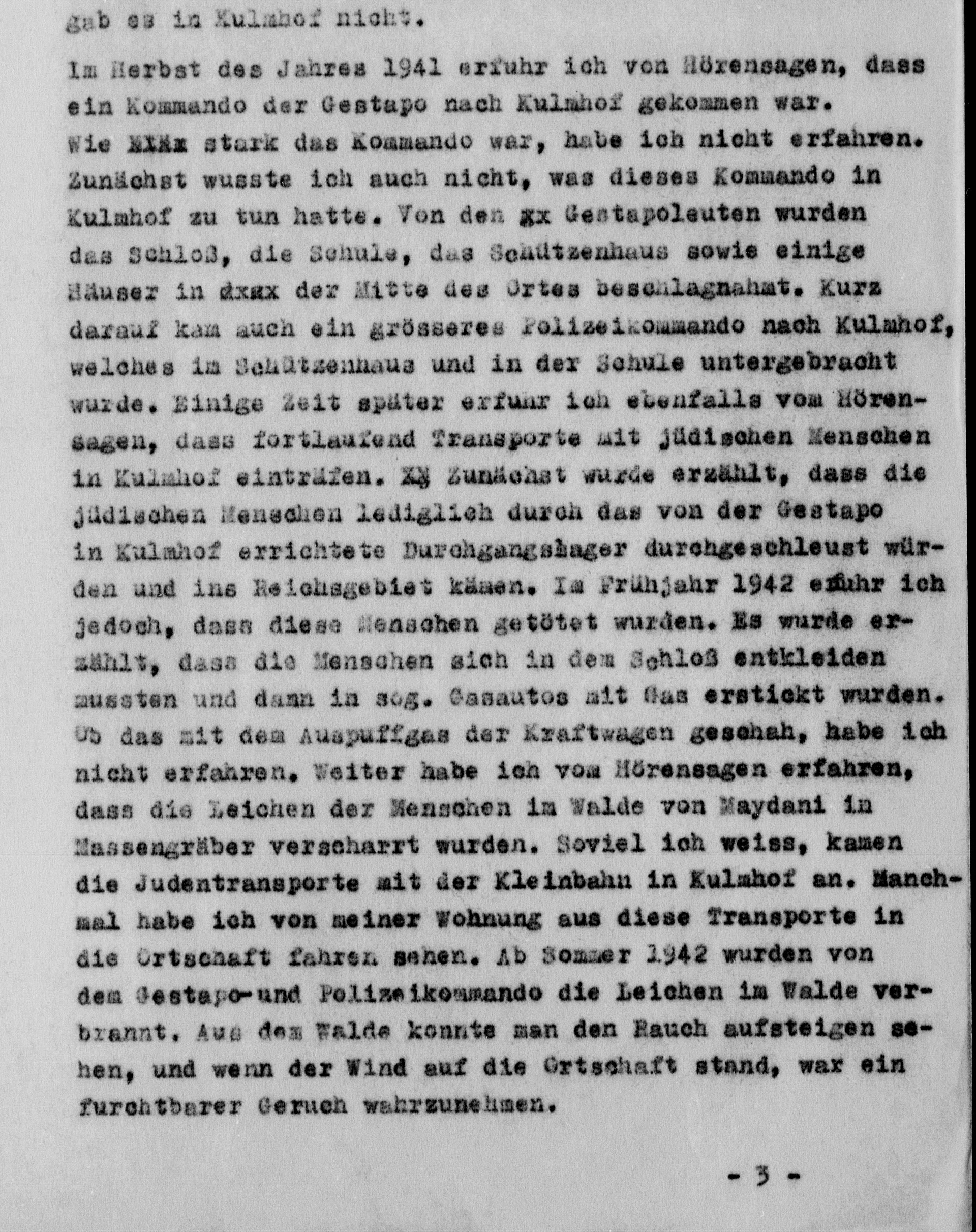

On April 16, 1962, Adele Freigang, former resident of the village Chełmno nad Nerem (Kulmhof), provided a detailed testimony to

Interrogation protocol of Josef Peham, dated December 12, 1962, on his experiences in Kulmhof (Chelmno) extermination camp.

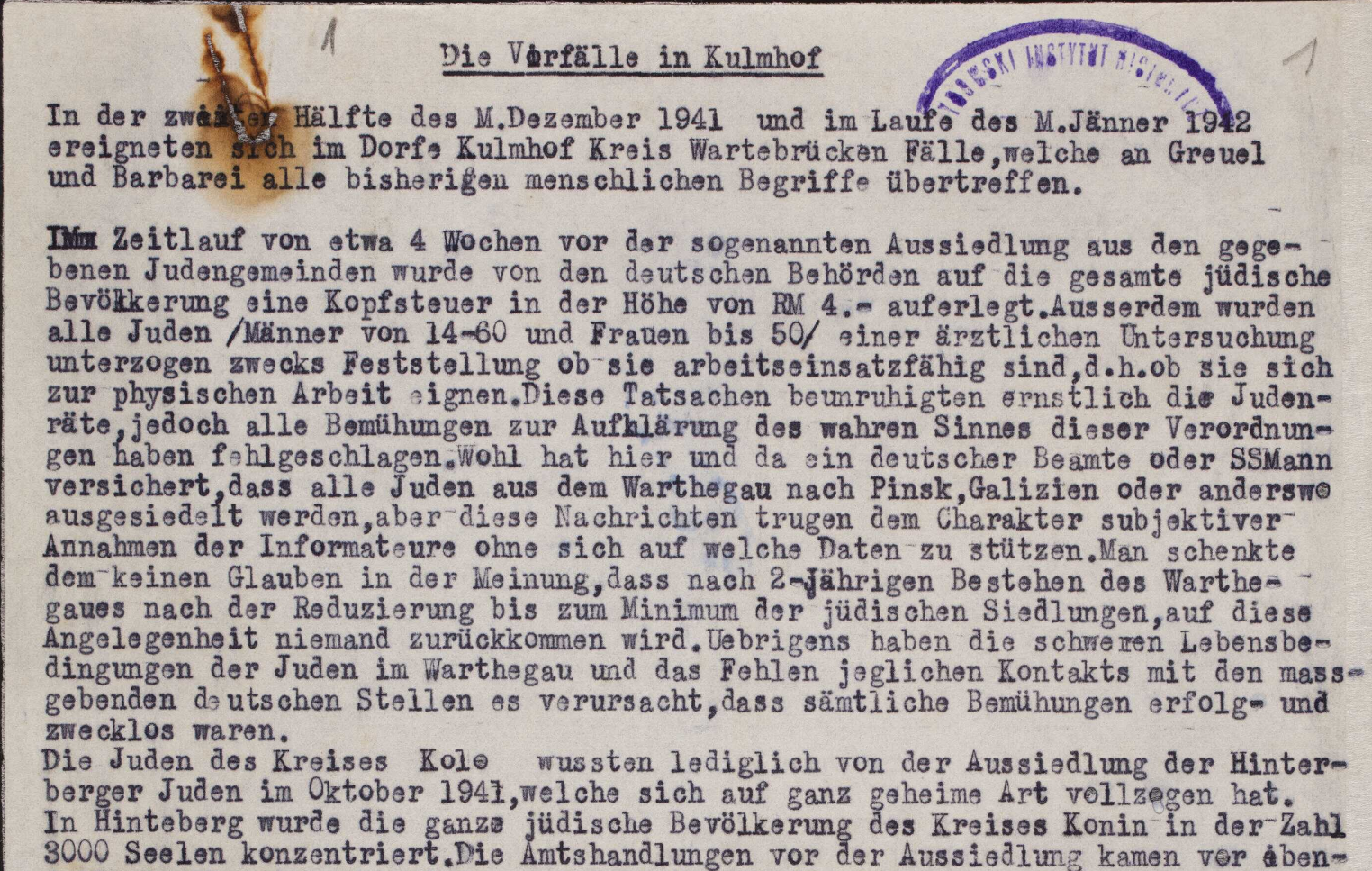

In a report titled "The Incidents in Kulmhof," Hersz Wasser, the secretary of the Warsaw Ghetto underground organisation Oneg Shabbbat,

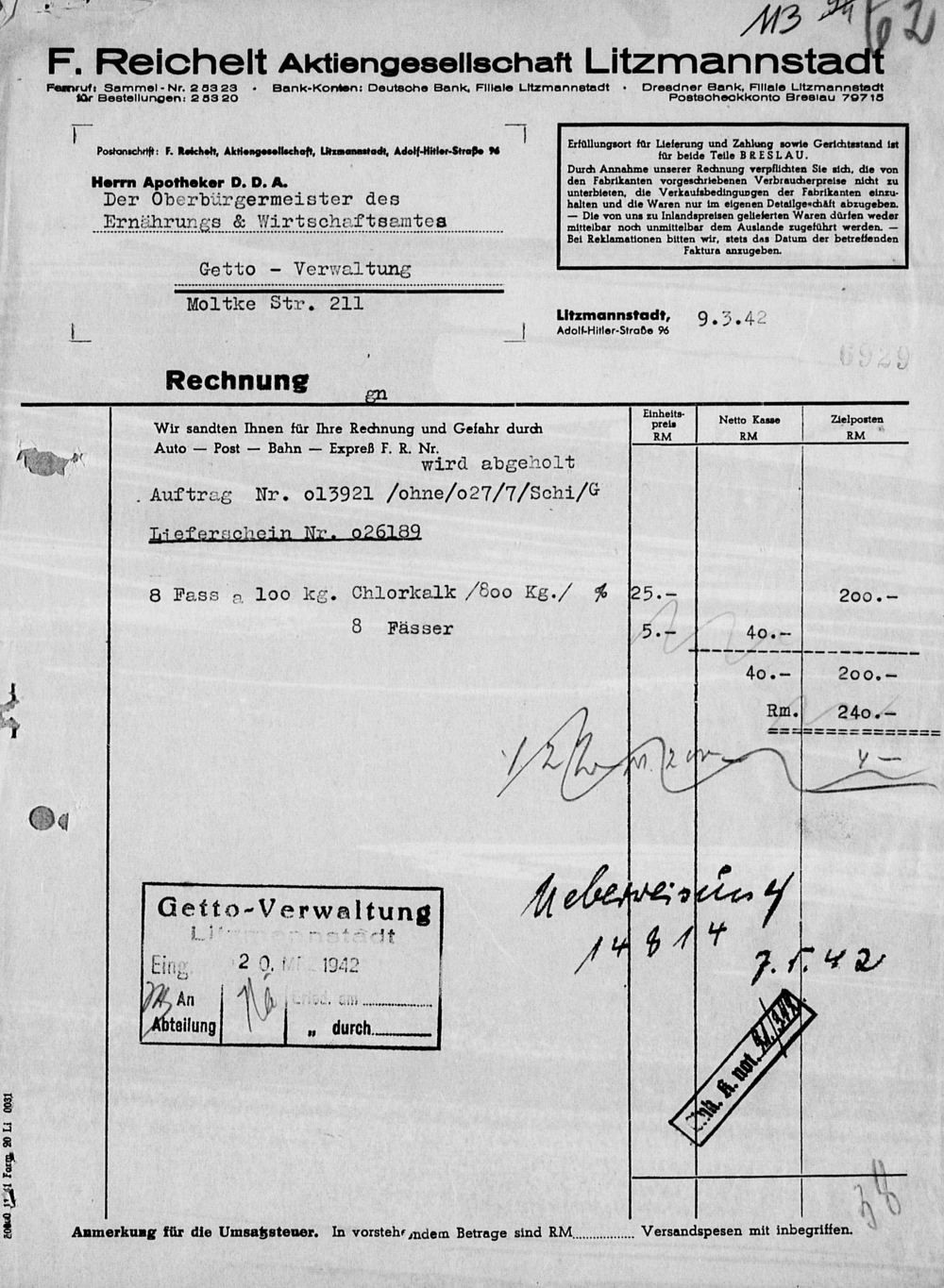

On 8 March 1942, the F. Reichelt Aktiengesellschaft Litzmannstadt, a Pharmaceutical Company, issued an invoice to the Ghetto Administration in

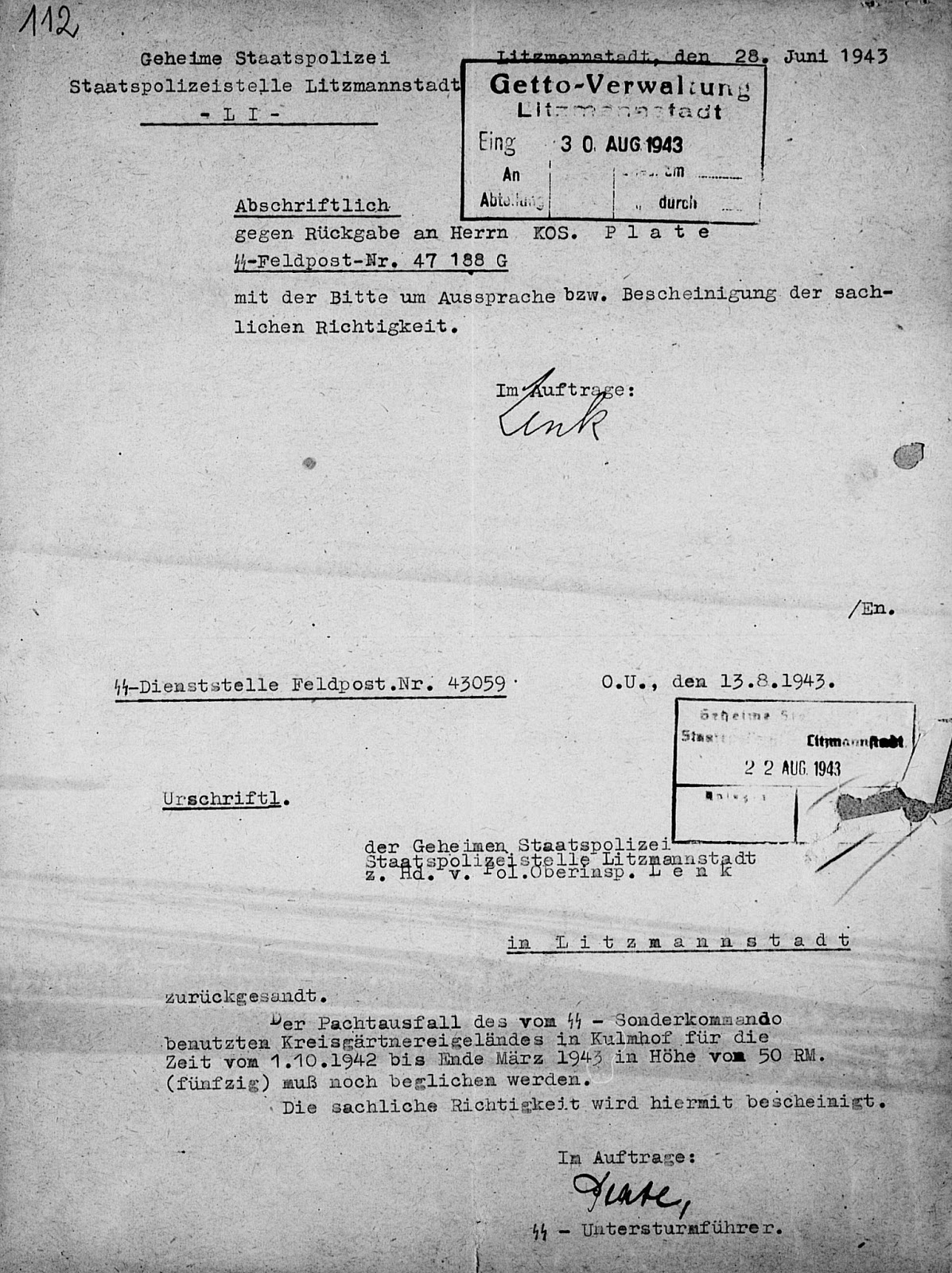

Albert Plate, deputy commander of Kulmhof extermination camp, confirmed the correctness of the claim by Walter Becht, Disctrict Administrator of

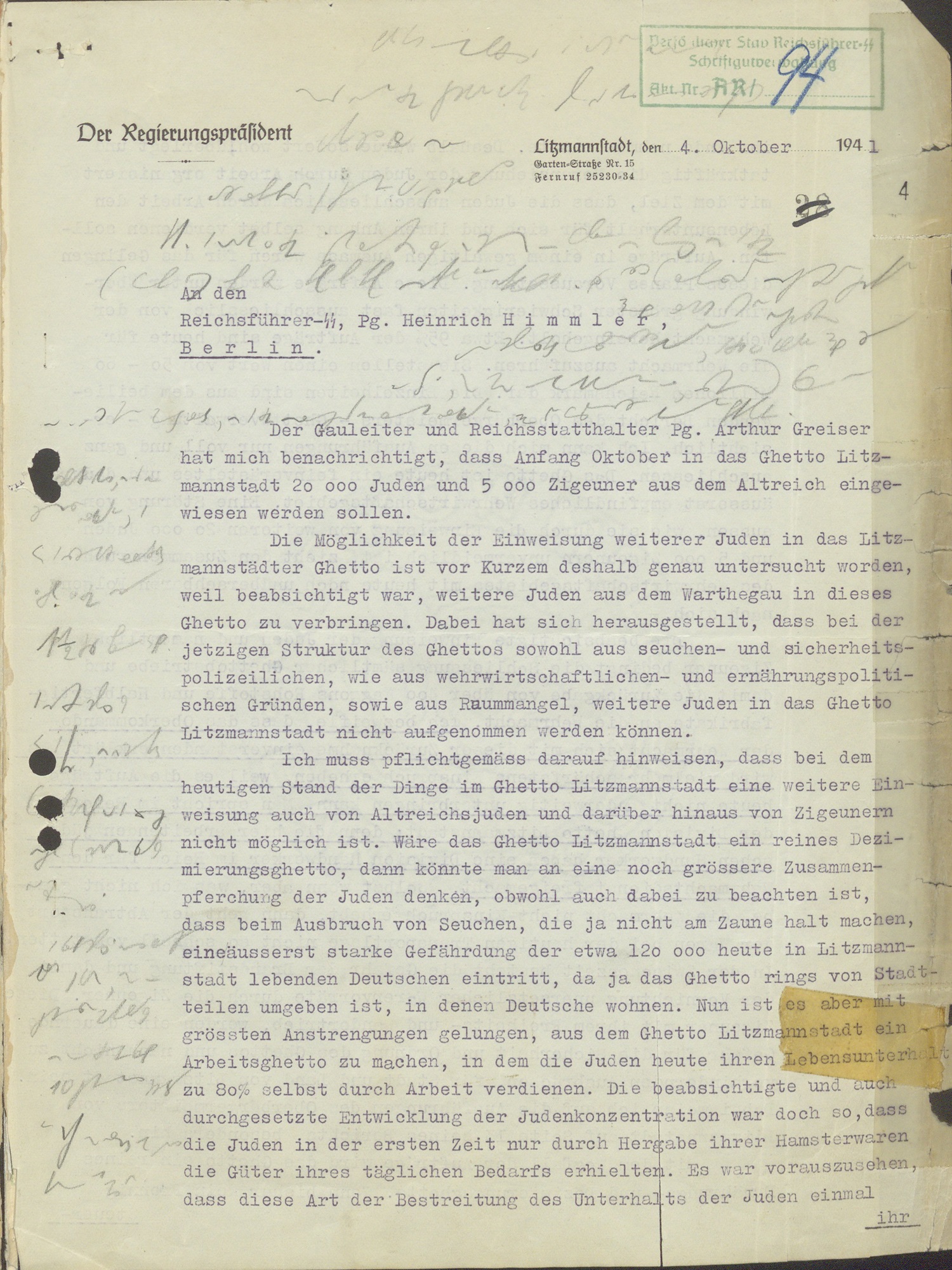

On October 4, 1941, the Government President of Litzmannstadt, Friedrich Uebelhoer, wrote to Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, addressing the planned transfer

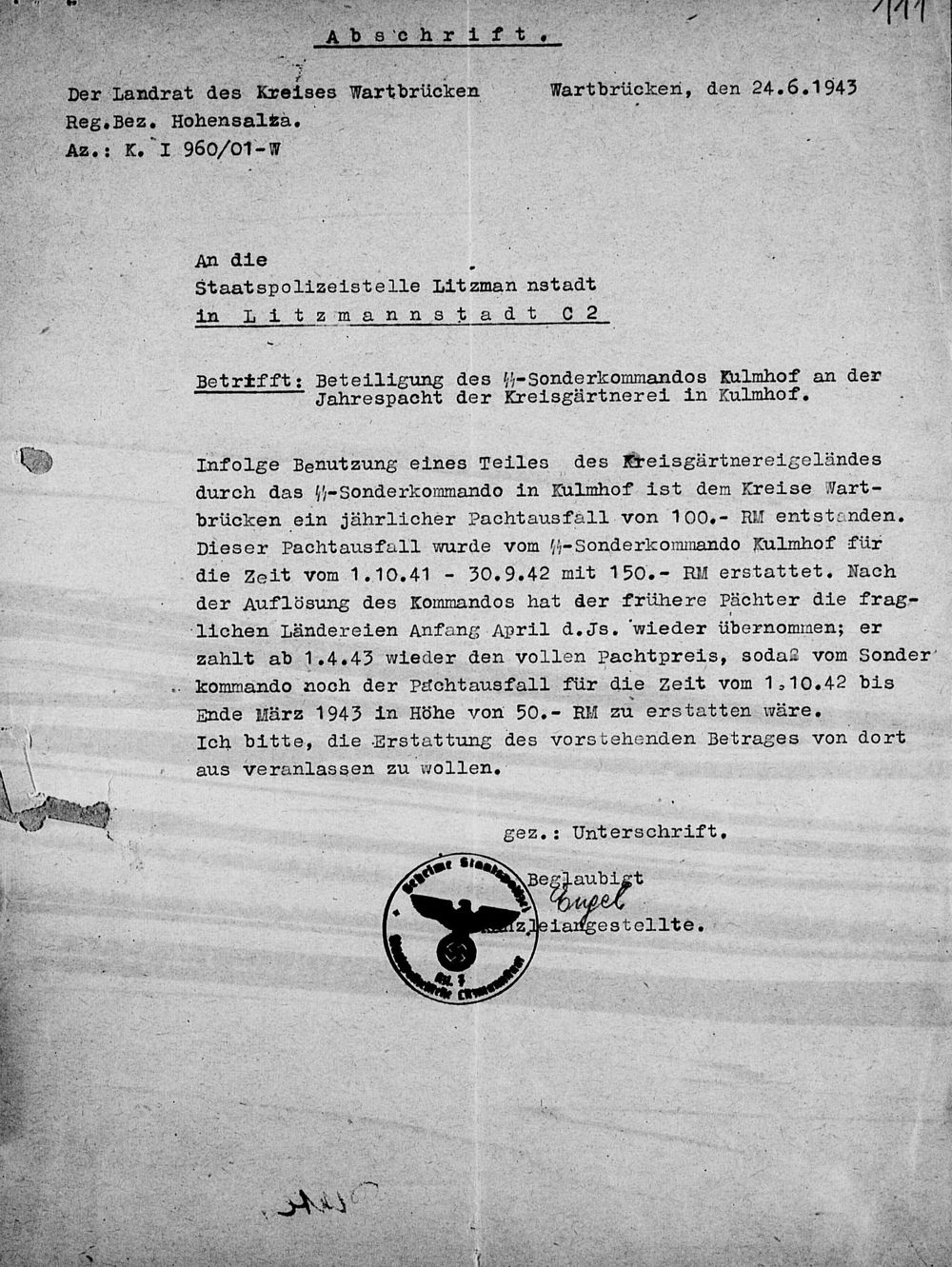

The letter dated June 24, 1943 was sent from Walter Becht, Disctrict Administrator of Warthbrücken (Kolo) to the State

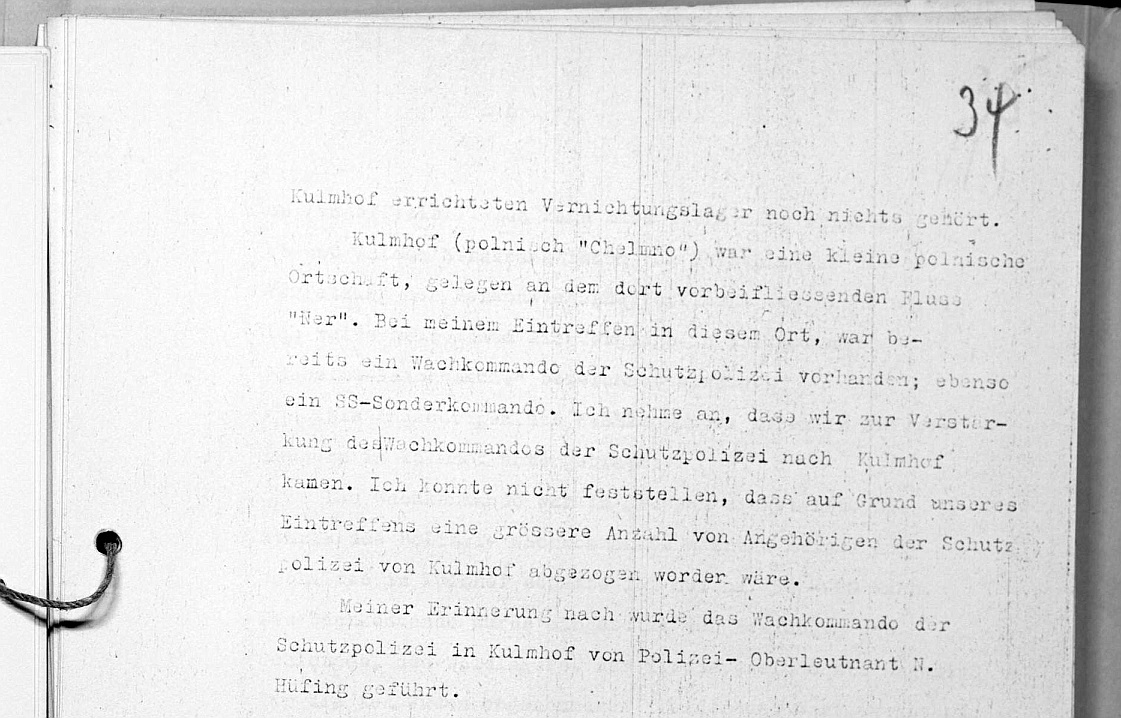

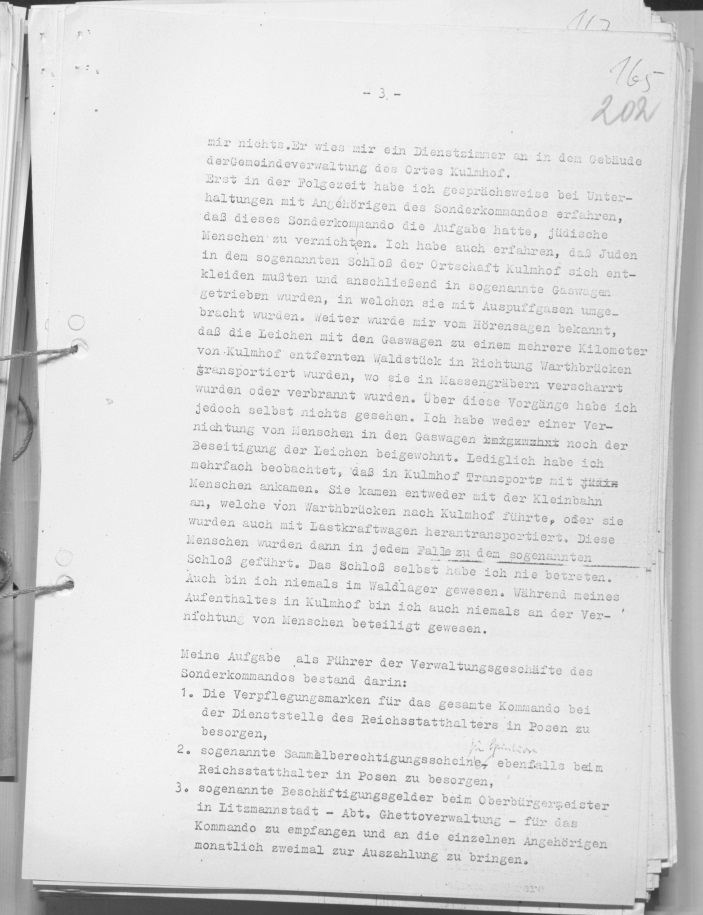

Interrogation protocol of Wilhelm Görlich, former member of the SS-Sonderkommando Kulmhof, dated 21 December 1960, recorded in Bonn on his

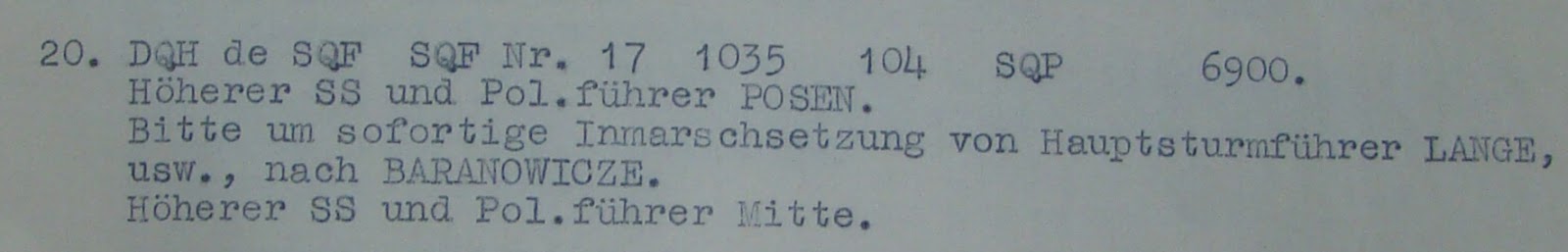

On 16 August, 1941, the British intelligence intercepted a radio message from the Higher SS and Police Leader Center, Erich

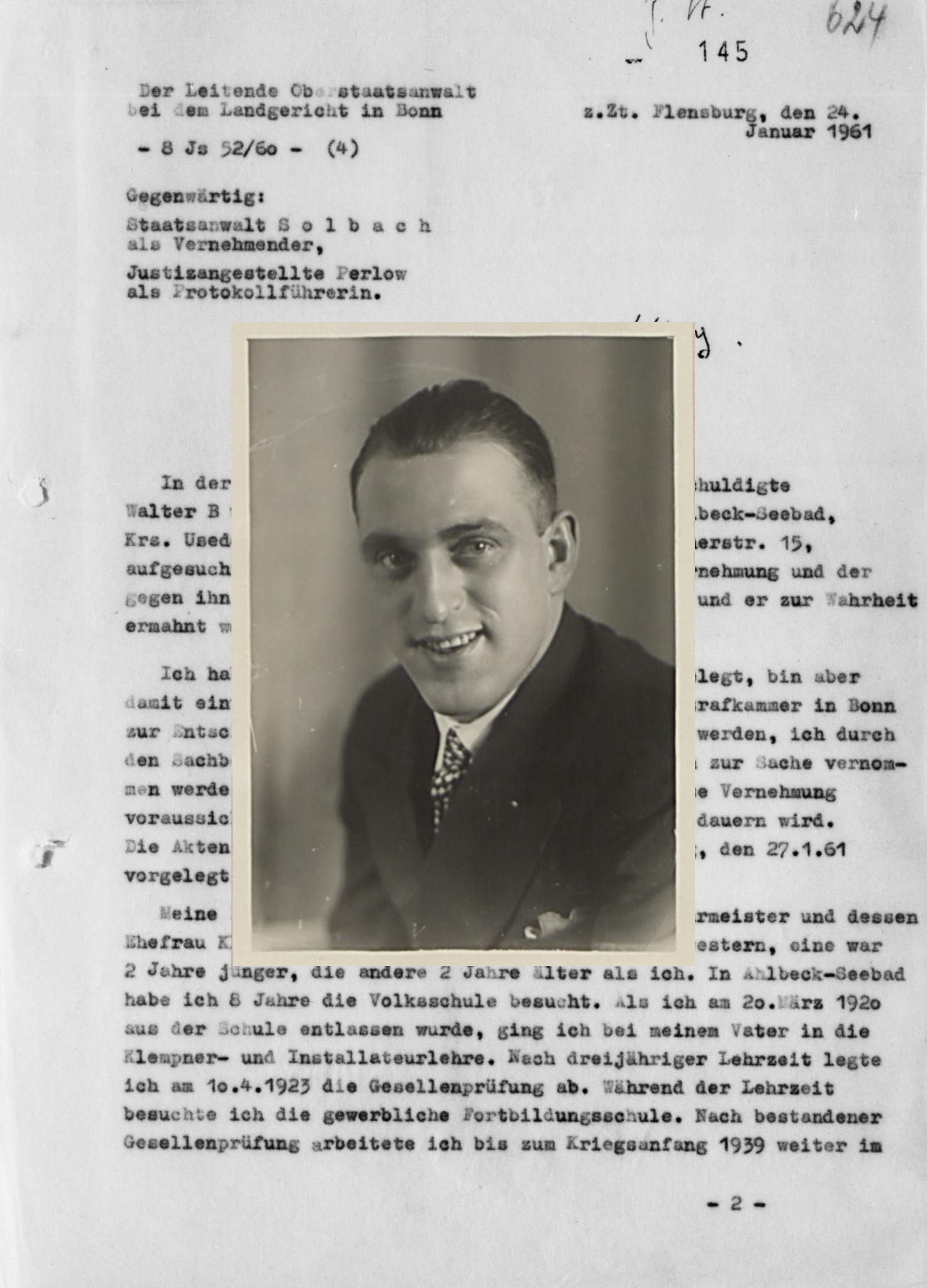

Interrogation protocol of Walter Burmeister, former member of the SS-Sonderkommando Kulmhof, dated 24 January 1961, recorded in Flensburg on his

Two days after Bach-Zelewski requested Sonderkommando Lange to come to Baranowicze, on August 18, 1941, the British intelligence intercepted another

Interrogation protocol of Fritz Ismer, former member of the SS-Sonderkommando Kulmhof, dated 9 November 1960, recorded in West-Berlin. Ismer mentions

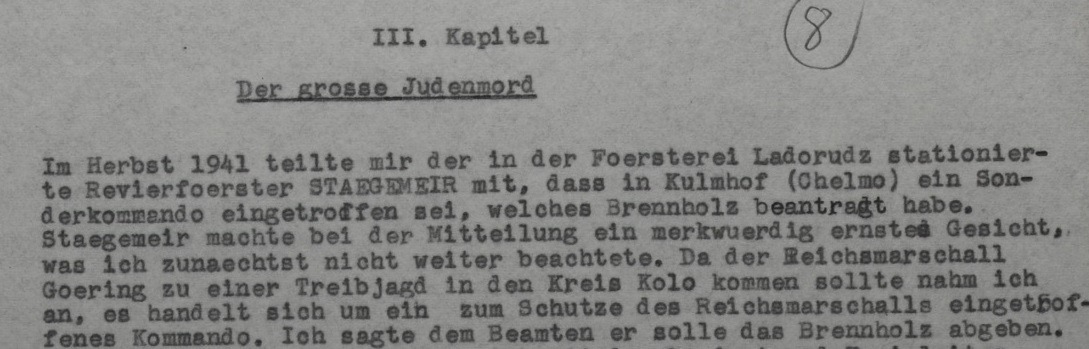

Certified copy of interrogation protocol of former forester Hans Staegemeir, dated 30 August 1961, recorded in Paderborn (West-Germany) on his

Certified copy of interrogation protocol of forestry official Heinrich May dated 13 December 1960, recorded in Bonn (West-Germany) on his

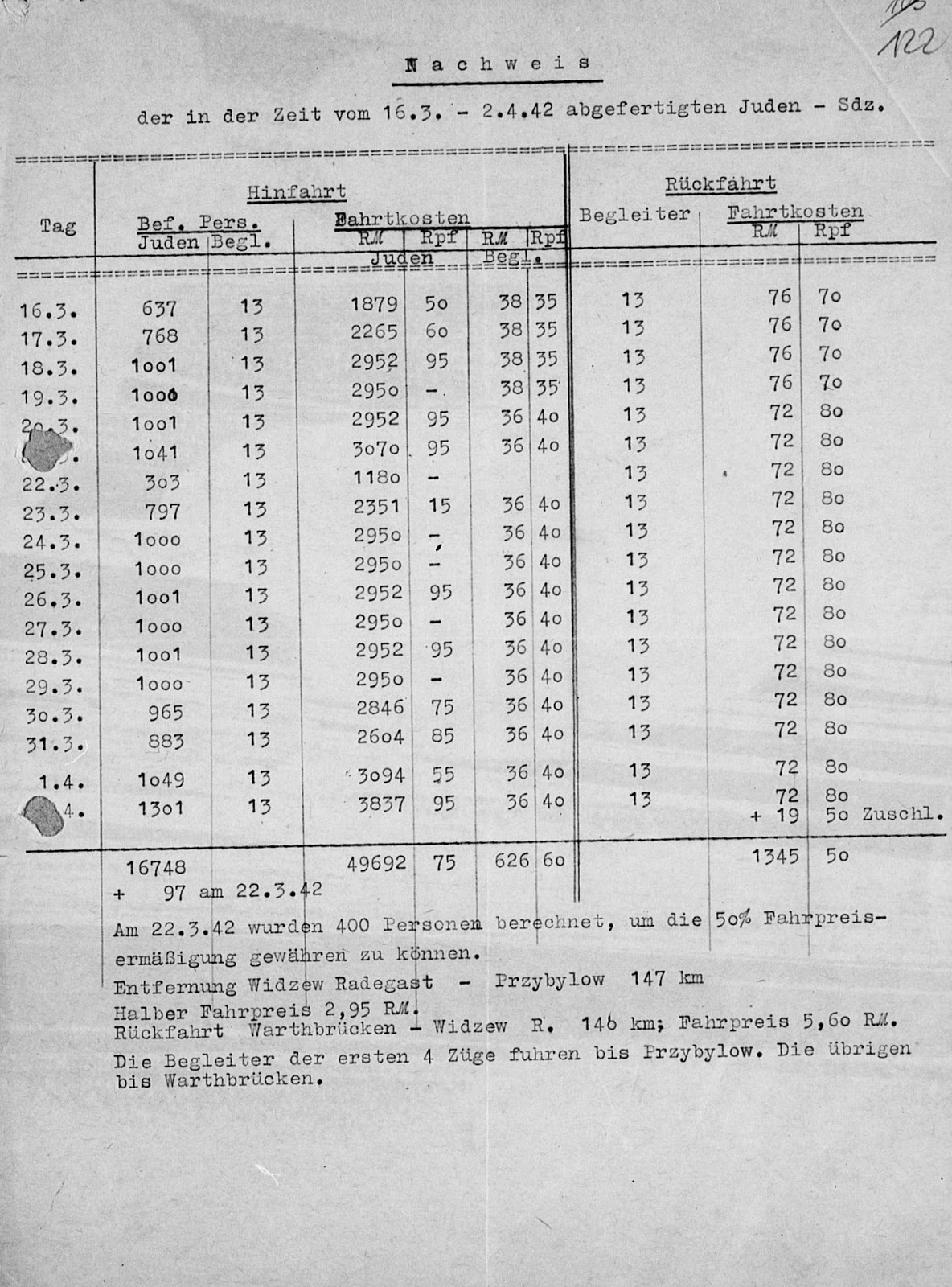

The document details a list of transports carrying 16,748 Jews from Radegast Station in the Łódź Ghetto to Przybyłów near

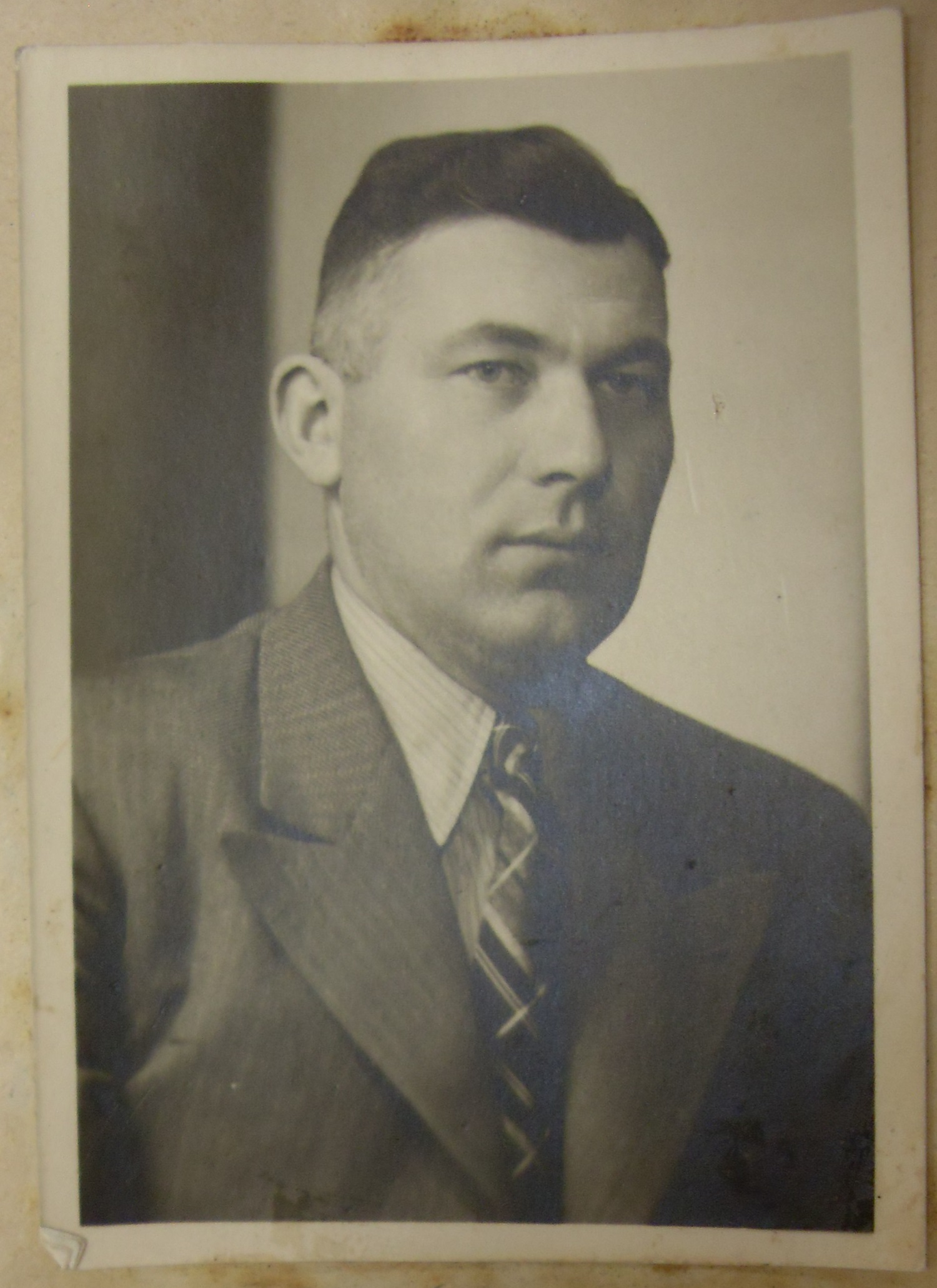

At the end of 1941, the SS-Sonderkommando leader Herbert Lange recruited Plate to the extermination camp Kulmhof. After the departure

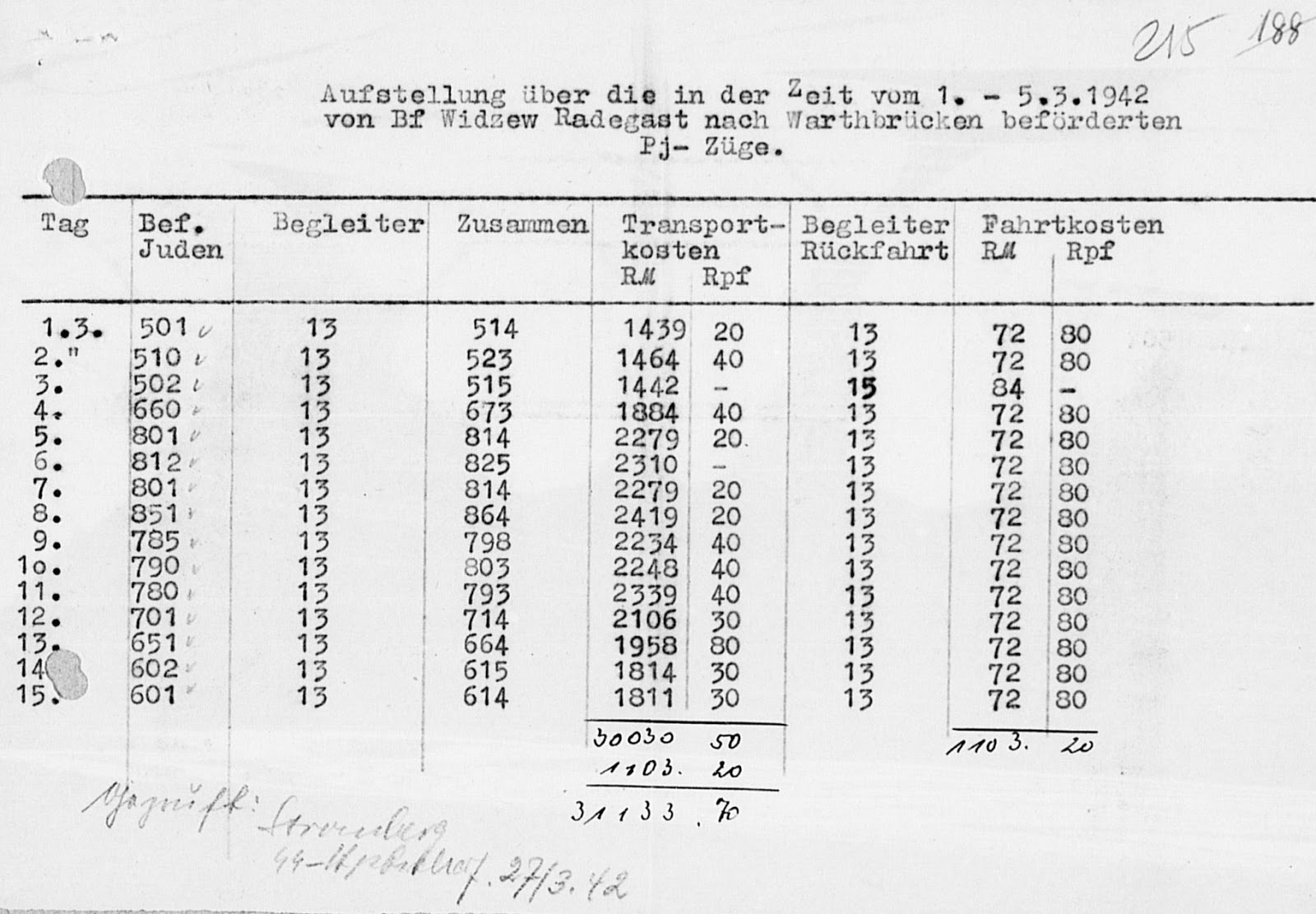

The document provides a list of transports with 10,348 Jews deported between March 1 and 15, 1942 from Radegast Station

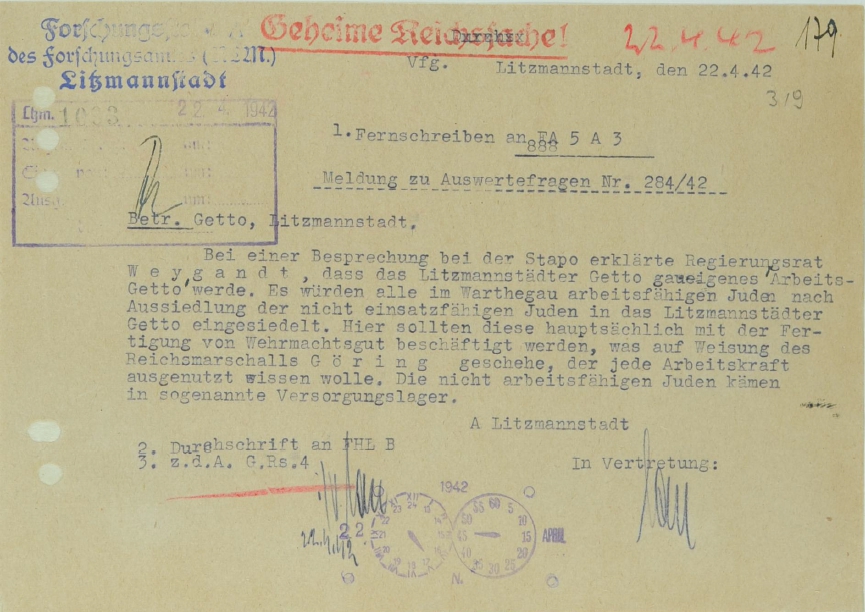

The document is dated April 22, 1942 and was written by Forschungsstelle A Litzmannstadt (Łódź), a local branch of

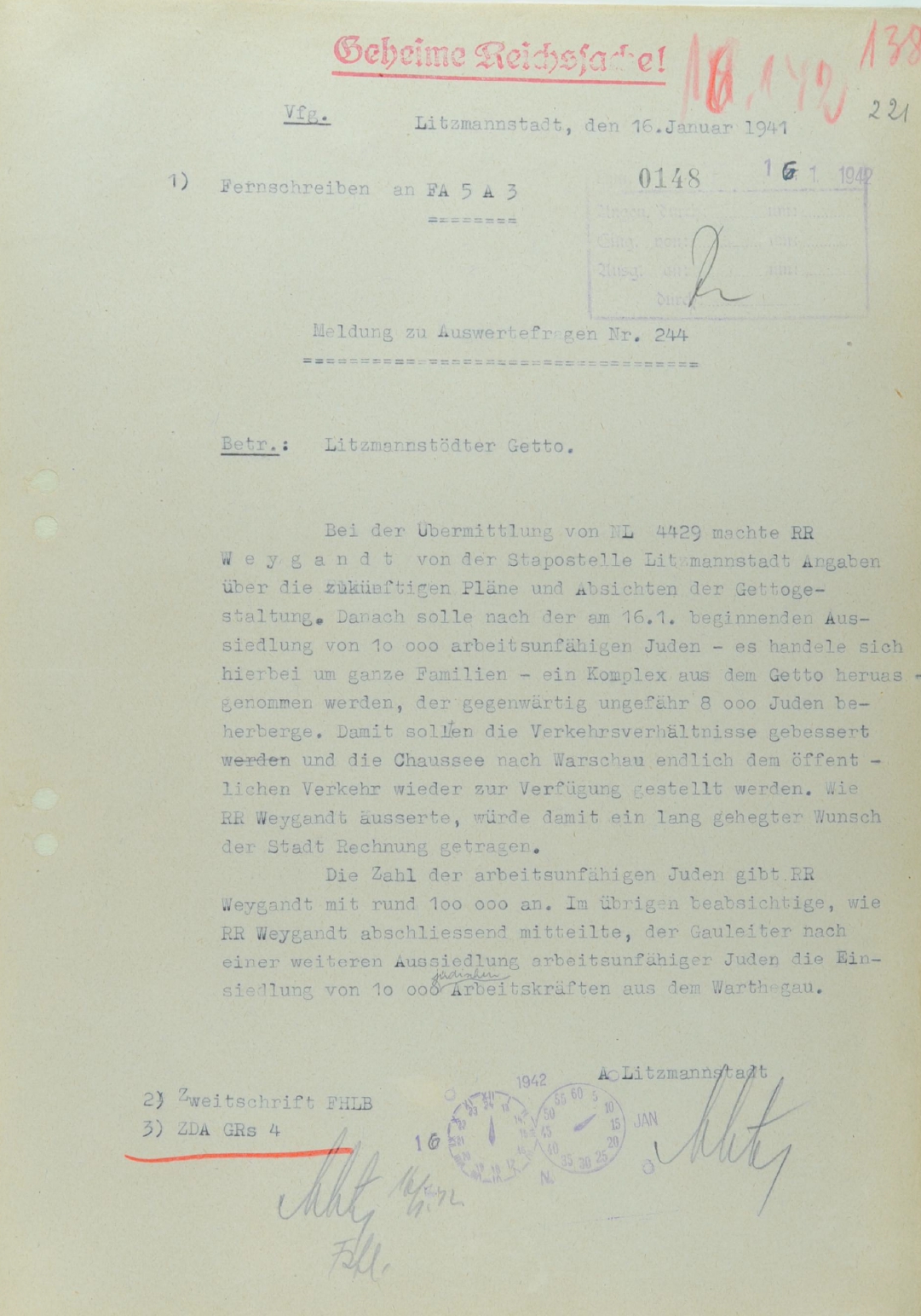

The document, dated January 16, 1941, was addressed from Forschungsstelle A in Litzmannstadt to Forschungsamt 5 A 3. Both offices

The telex, dated December 9, 1941, was sent from Forschungsstelle A Litzmannstadt to Forschungsamt 5 A 3, both of which

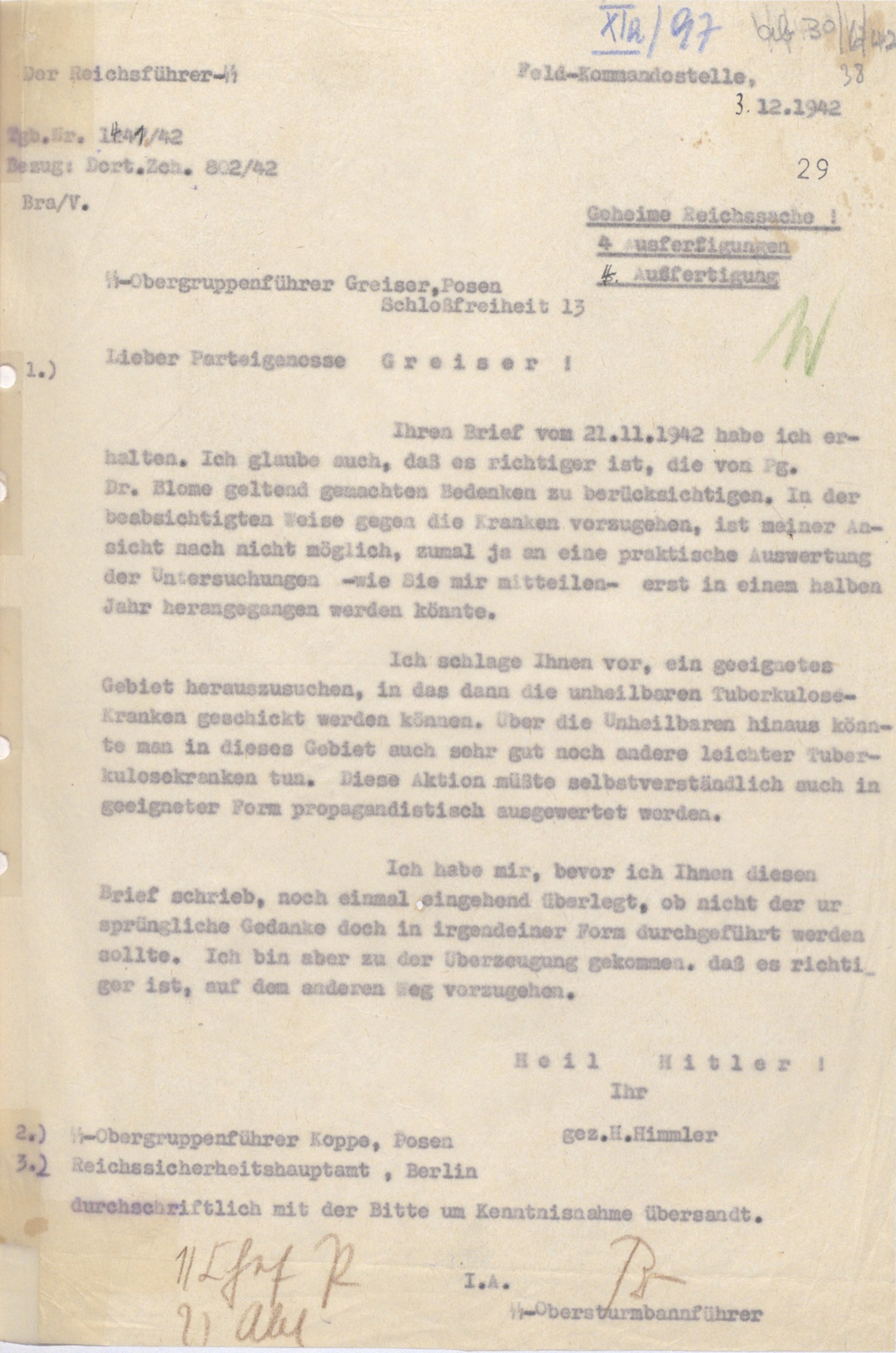

The letter, dated December 3, 1942, from Himmler to SS-Obergruppenführer Greiser, acknowledges Dr. Blome's concerns regarding the proposed plan to

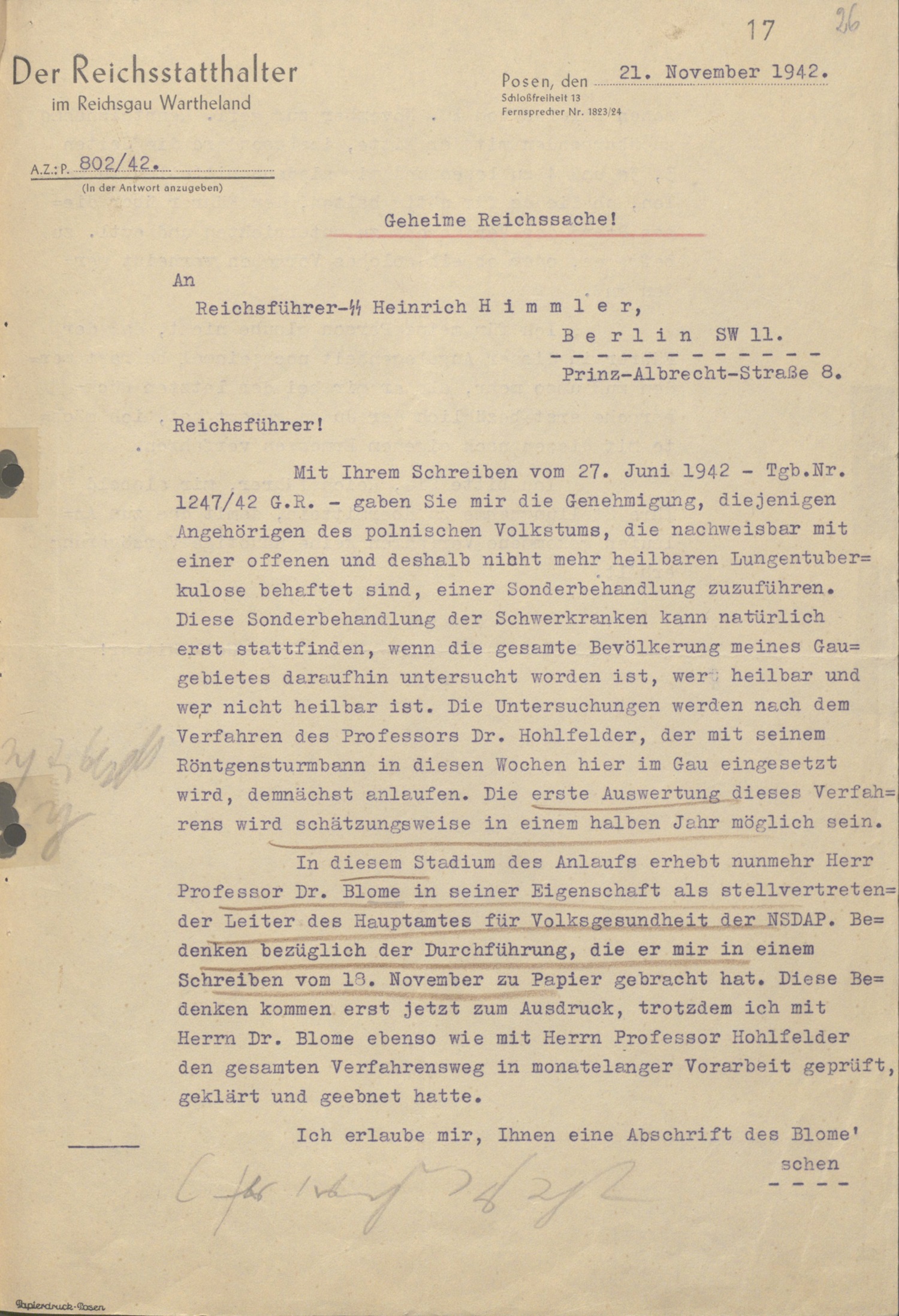

The letter, dated November 21, 1942, from the Reich Governor of the Reichsgau Wartheland Posen to Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, discusses

While the Nazi authorities in the Warthegau were already planning the killing of Polish individuals incurably afflicted with tuberculosis, concerns

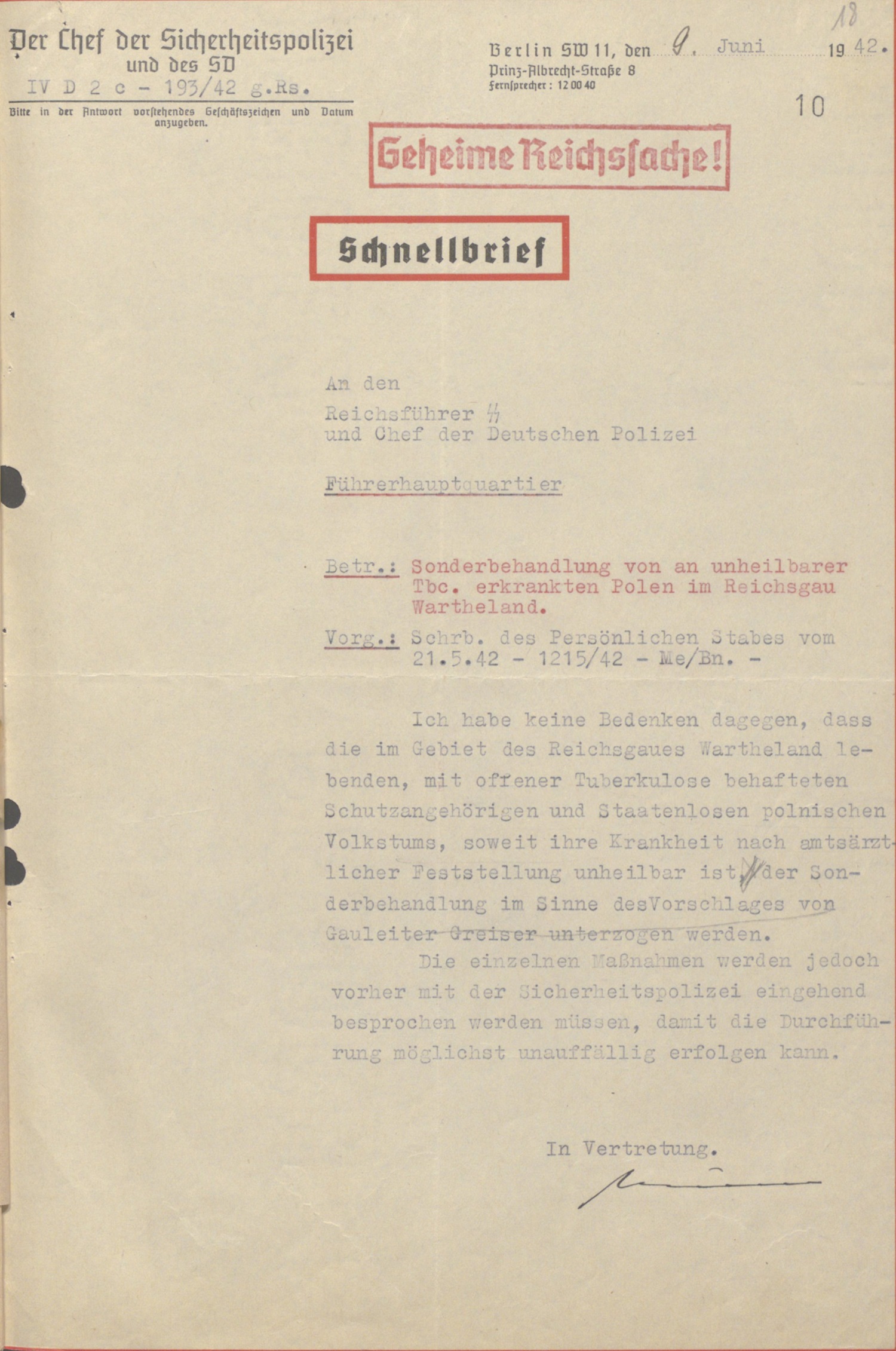

After receiving the request from the government of the Warthegau to kill Polish nationals suffering from incurable tuberculosis through the

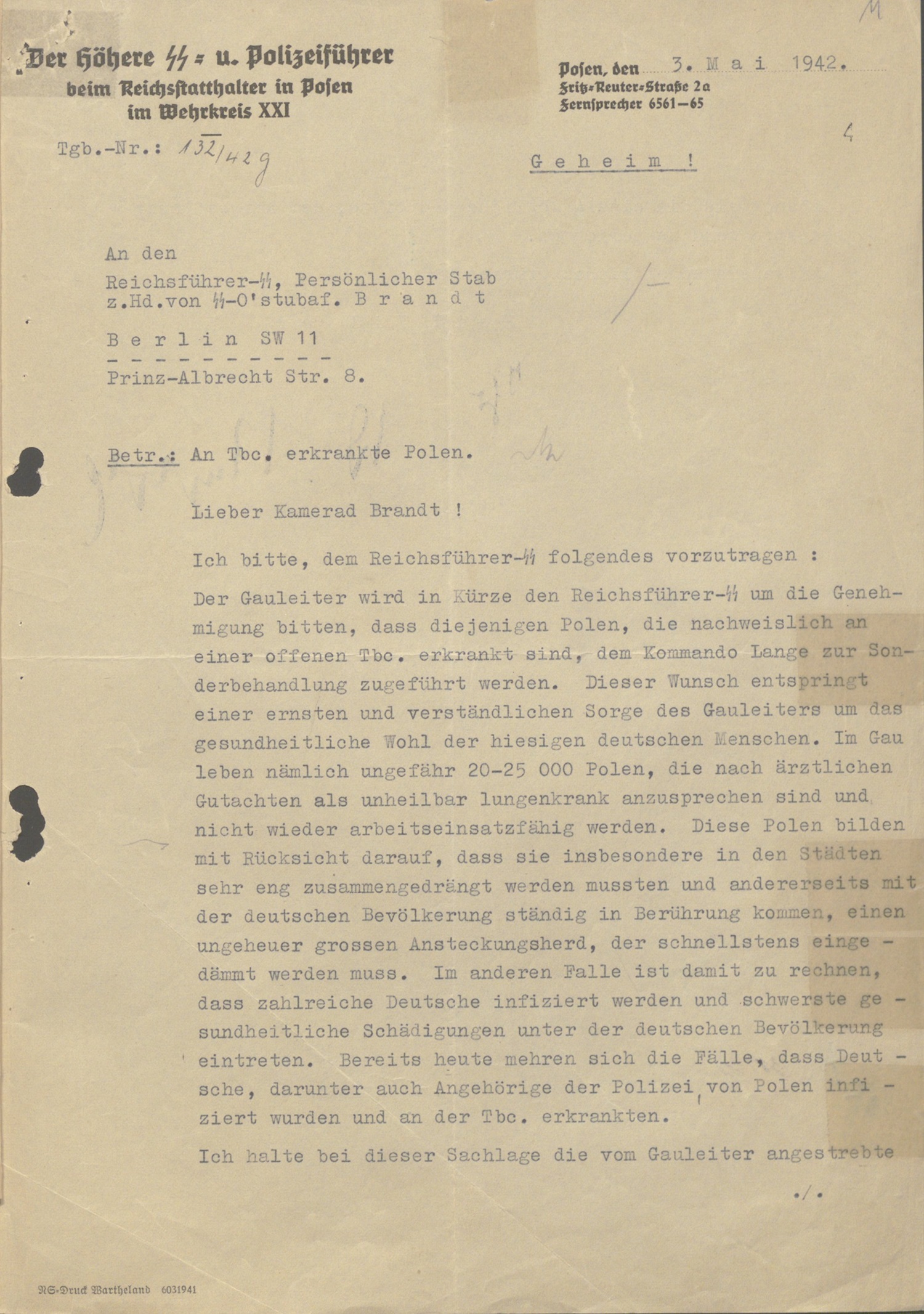

On May 3, 1942, in a coordinated action with the Reich Governor Arthur Greiser of the Reichsgau Wartheland, Wilhelm Koppe,

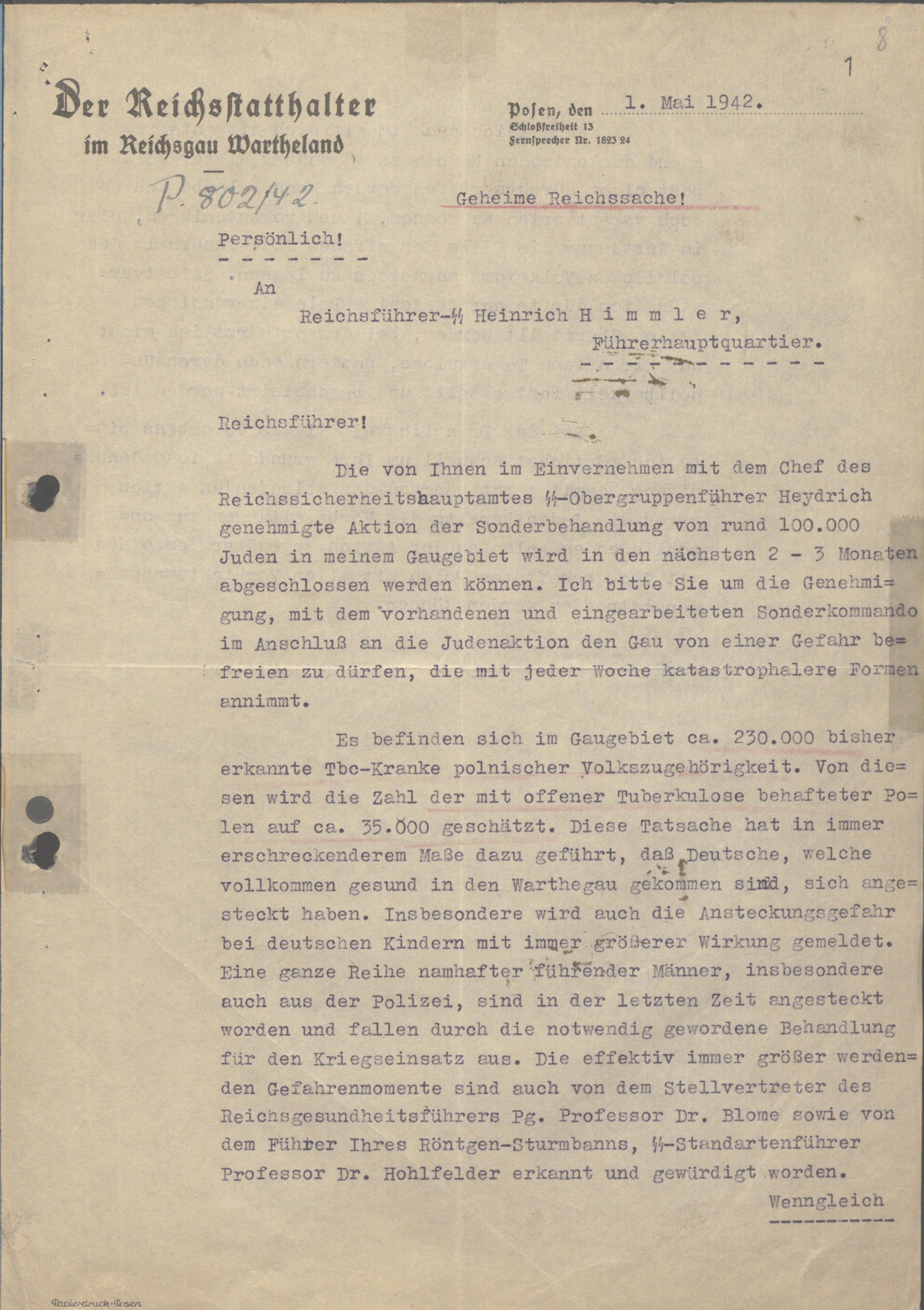

On May 1, 1942, Arthur Greiser, the Reich Governor in the Reichsgau Wartheland, relayed to Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler that "The

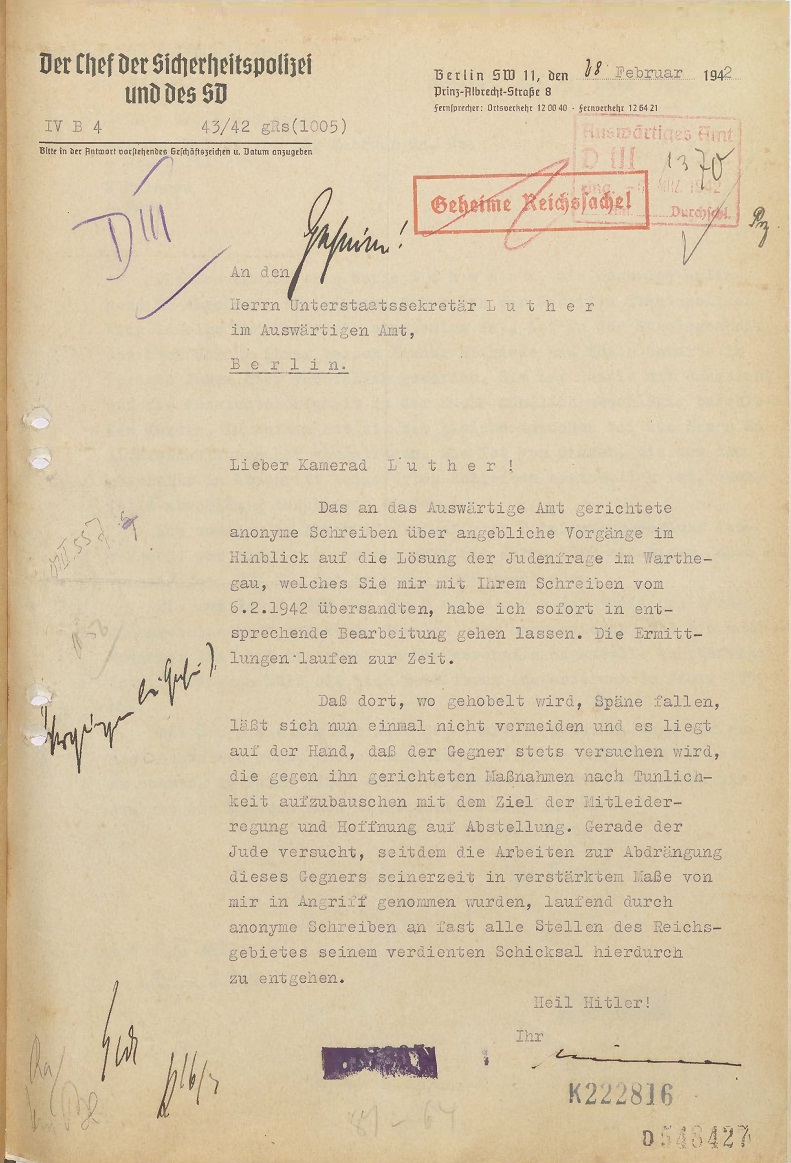

On February 6, 1942, Martin Luther of the German Foreign Office forwarded an anonymous letter to Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller.

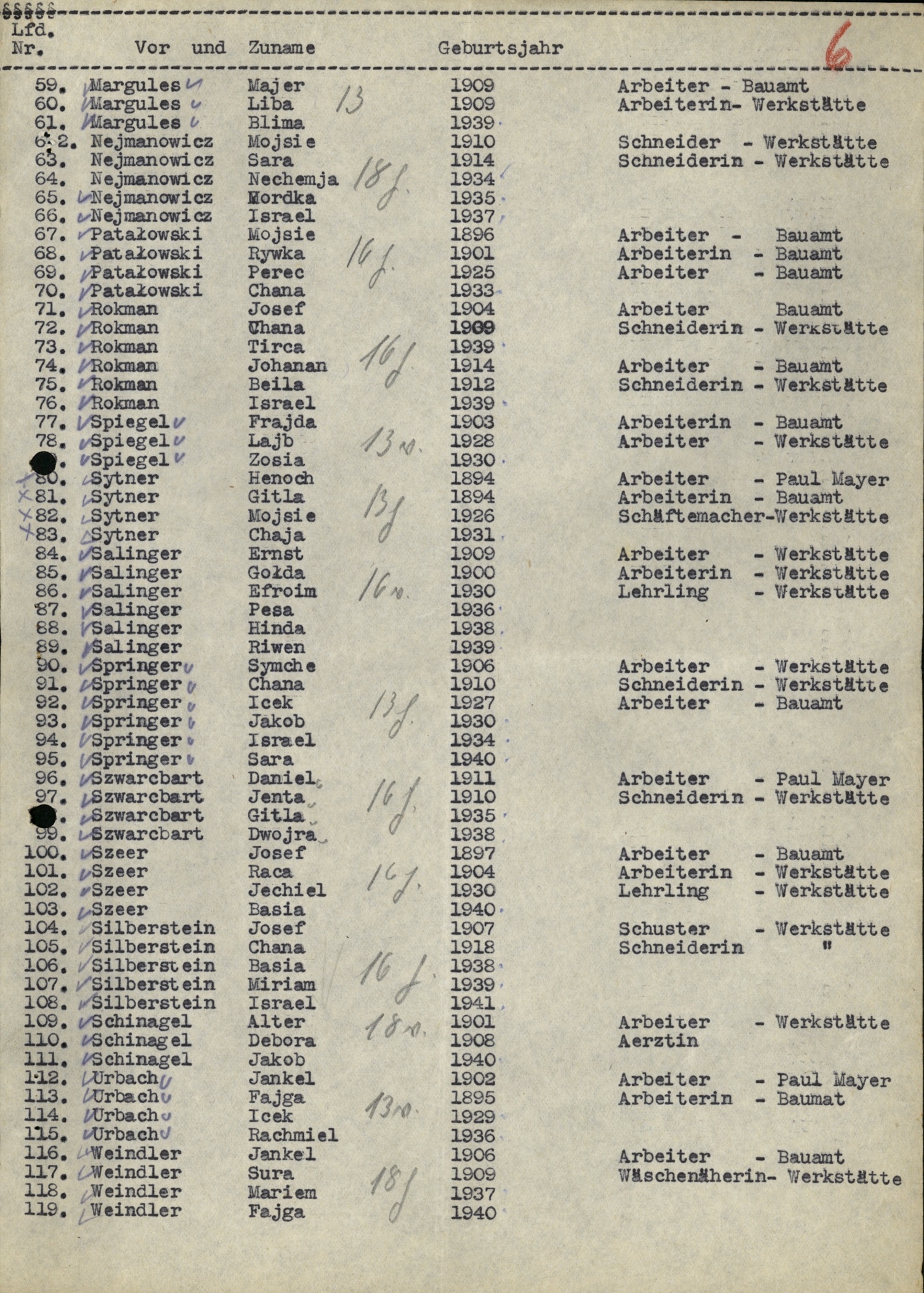

The document describes the fate of 127 individuals identified as "Jews with children under 14 years," deported from Kalisch by

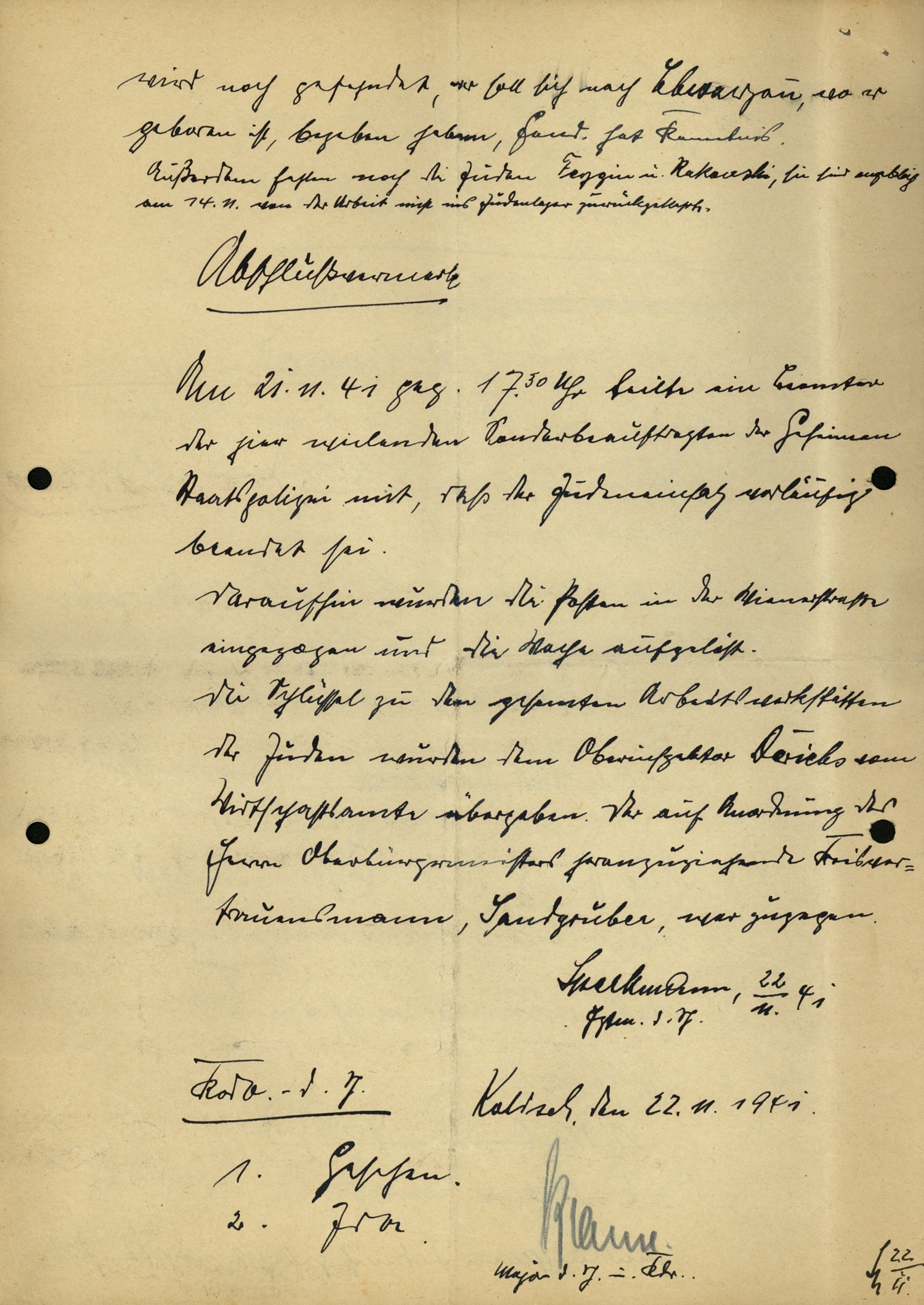

This document of November 22, 1941 was written by Hauptmann Speckmann from the regular police in Kalisch (Kalisz) and describes

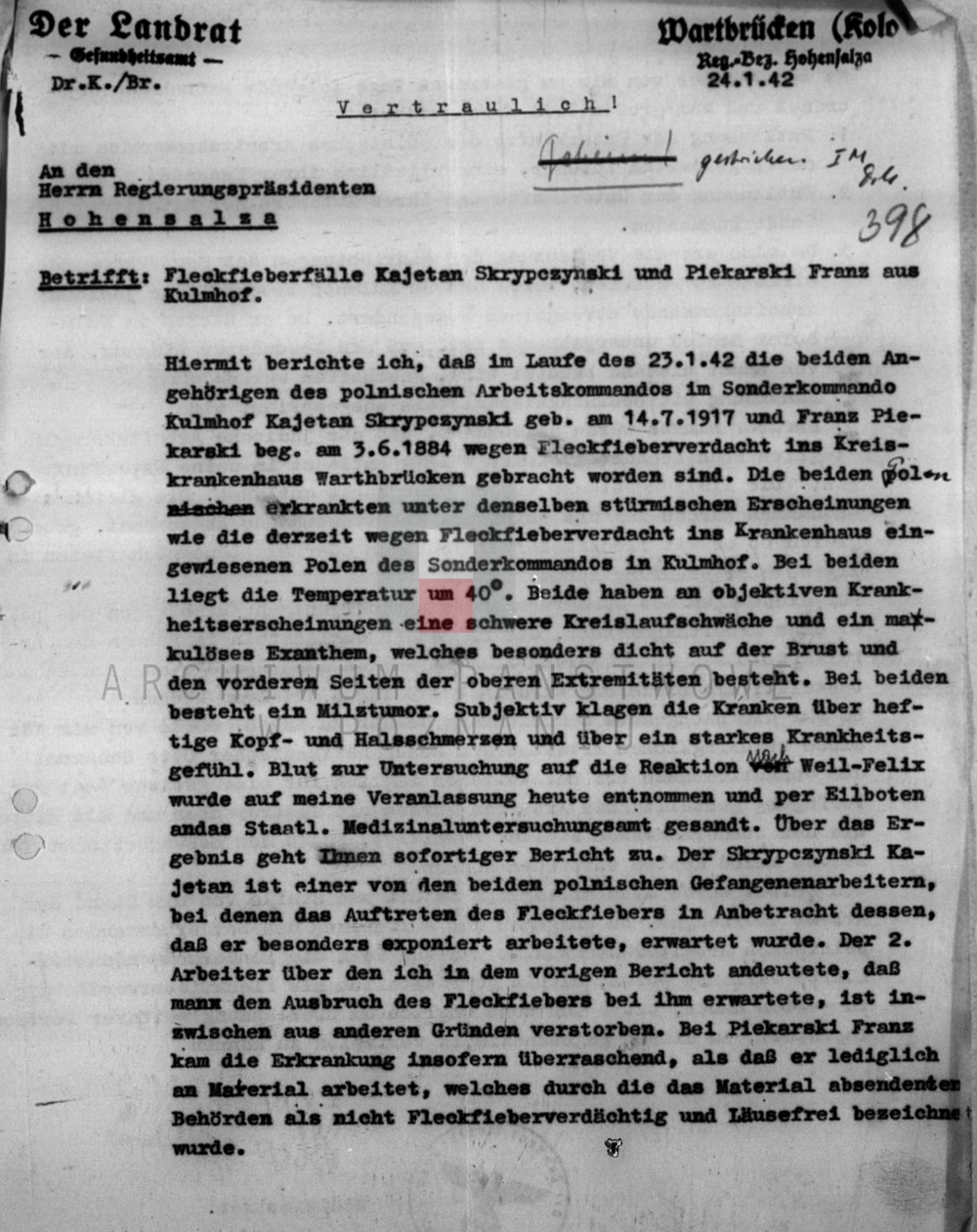

In January 1942, authorities in the Warthegau region grappled with the spread of typhus originating from Sinti and Roma victims,

On September 2, 1941, Rolf-Heinz Höppner, head of the Central Migration Office in Posen, outlined plans for reorganizing the office

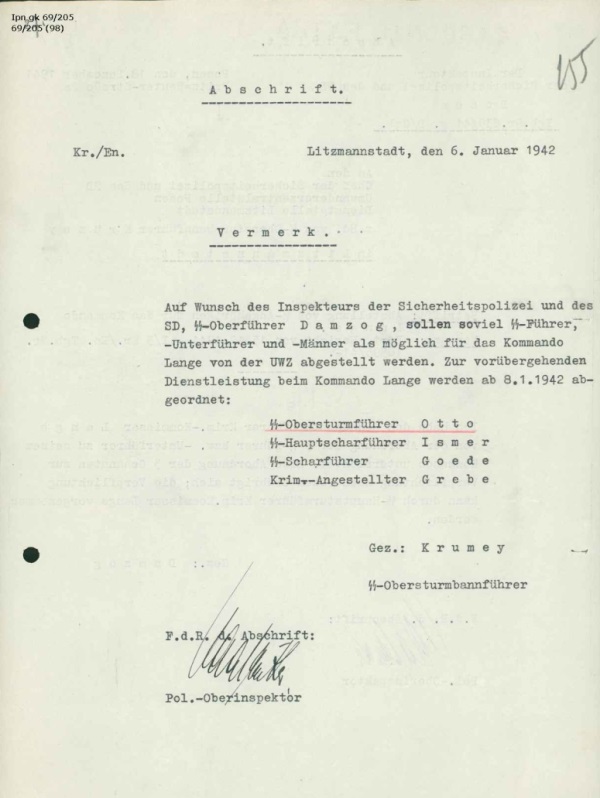

On January 6, 1942, Herman Krumey, the head of the Migration Central Office in Litzmannstadt, recorded the names of three

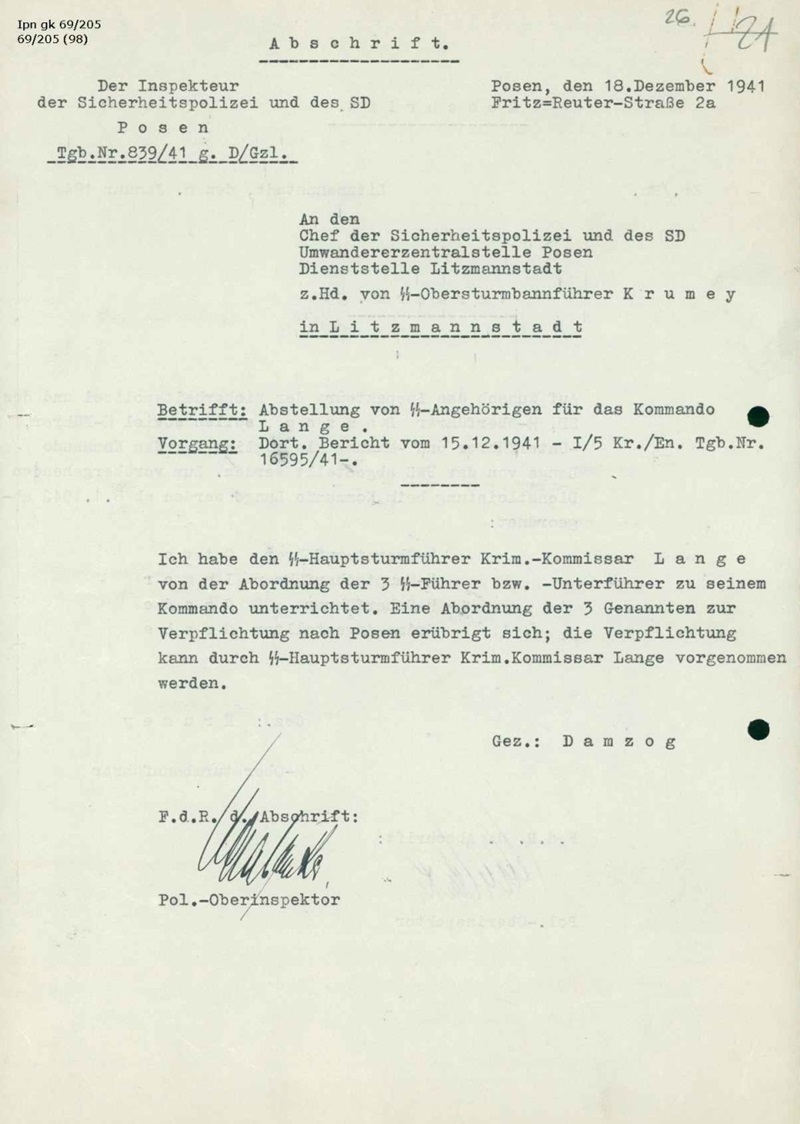

On December 18, 1941, Ernst Damzog, the Inspector of the Security Police and SD in Posen, wrote to Hermann Krumey,

Hans Staegemeir was forester of the area at Kulmhof extermination camp. He observed the activities of theSonderkommando and shared his

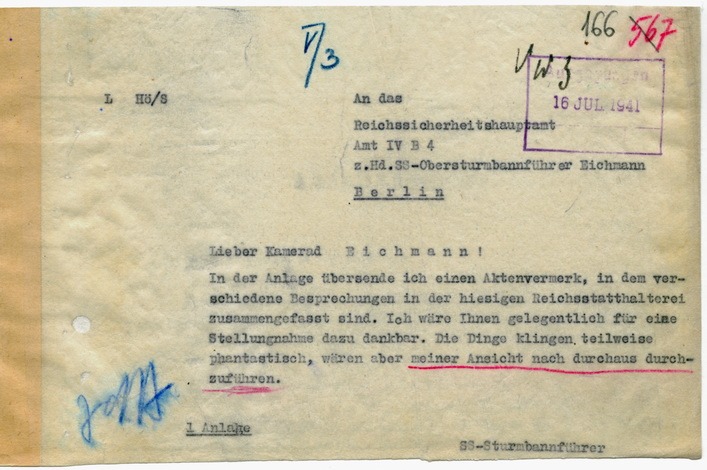

On July 16, 1941, authorities in the Reichsgau Wartheland convened to deliberate on what was euphemistically termed the "solution of

The following report, dated February 1945, was authored by Heinrich May, detailing his experience and knowledge of the Kulmhof (Chelmno)

In March 1942, Bothmann assumed the role of commander at the Kulmhof extermination camp, succeeding Herbert Lange in this position.

Heinrich May served as the head of the forestry office in Warthbrücken (now Koło) within the Warthegau region, which included

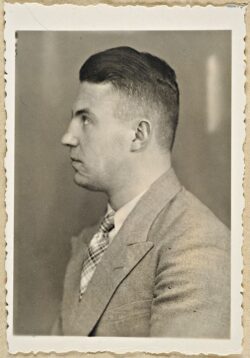

Lange oversaw the infamous Sonderkommando Lange and subsequently assumed command at the Kulmhof extermination camp. In this capacity, he bore