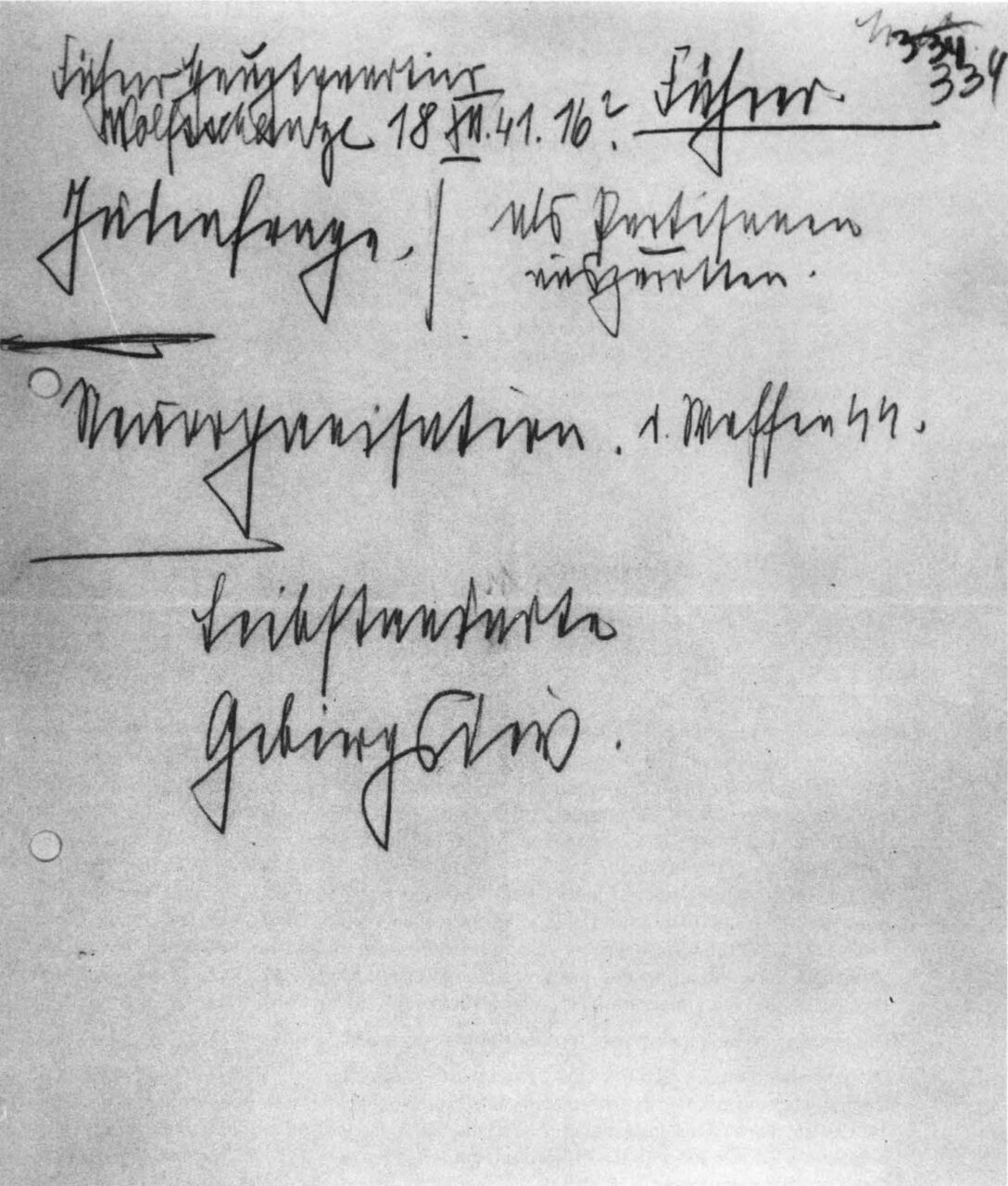

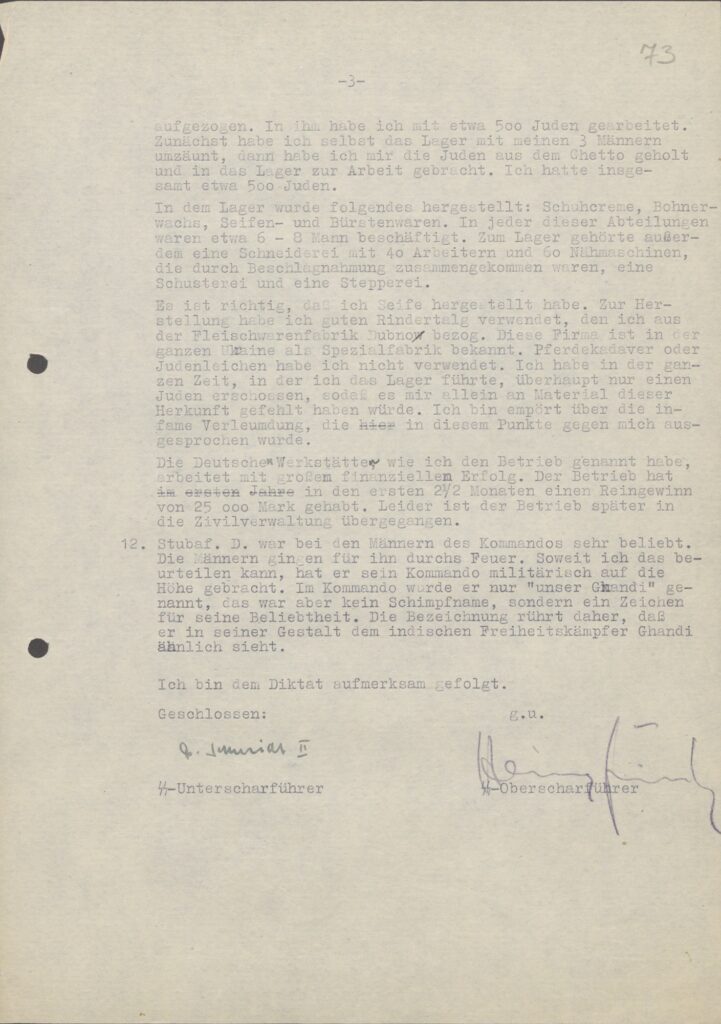

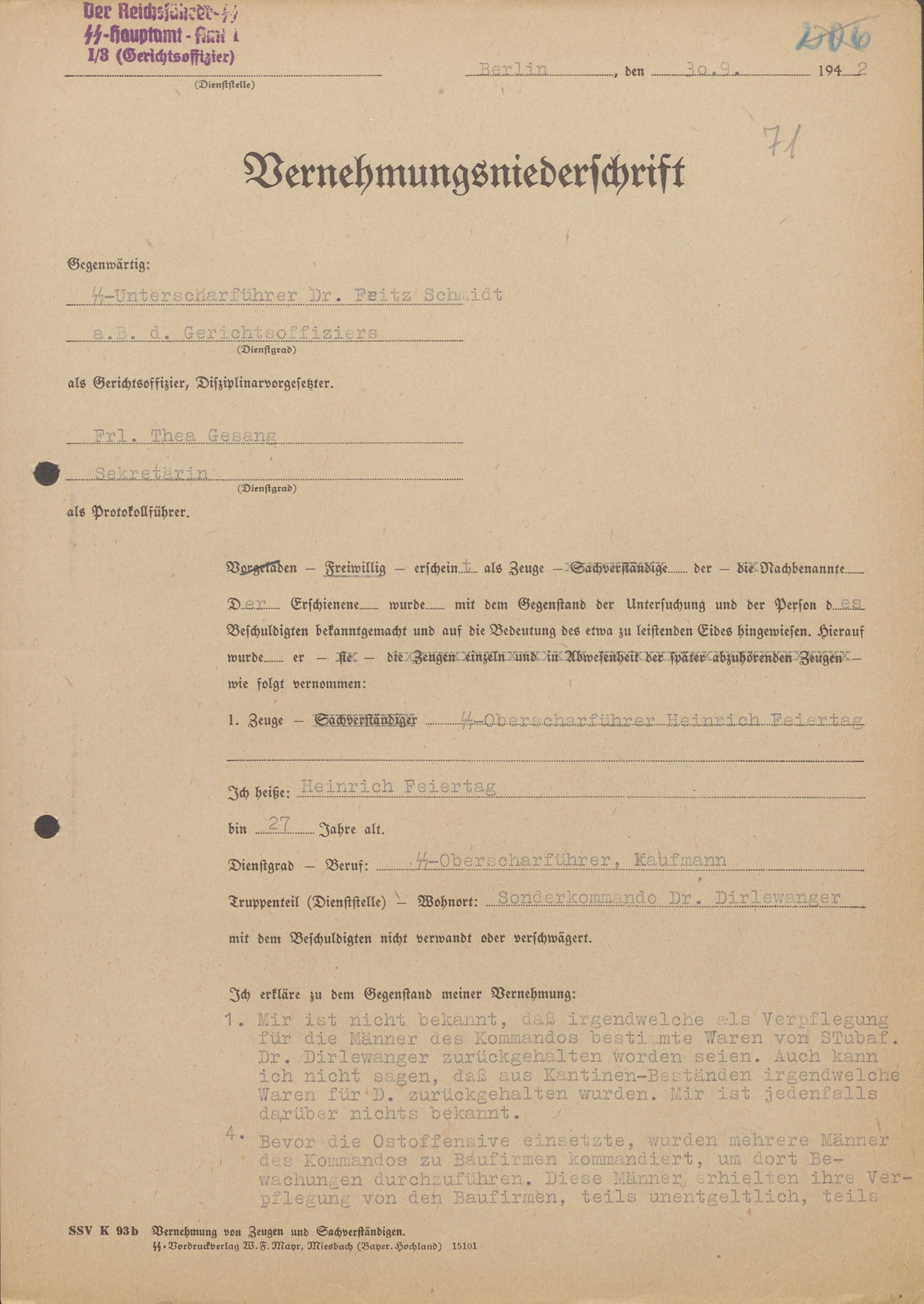

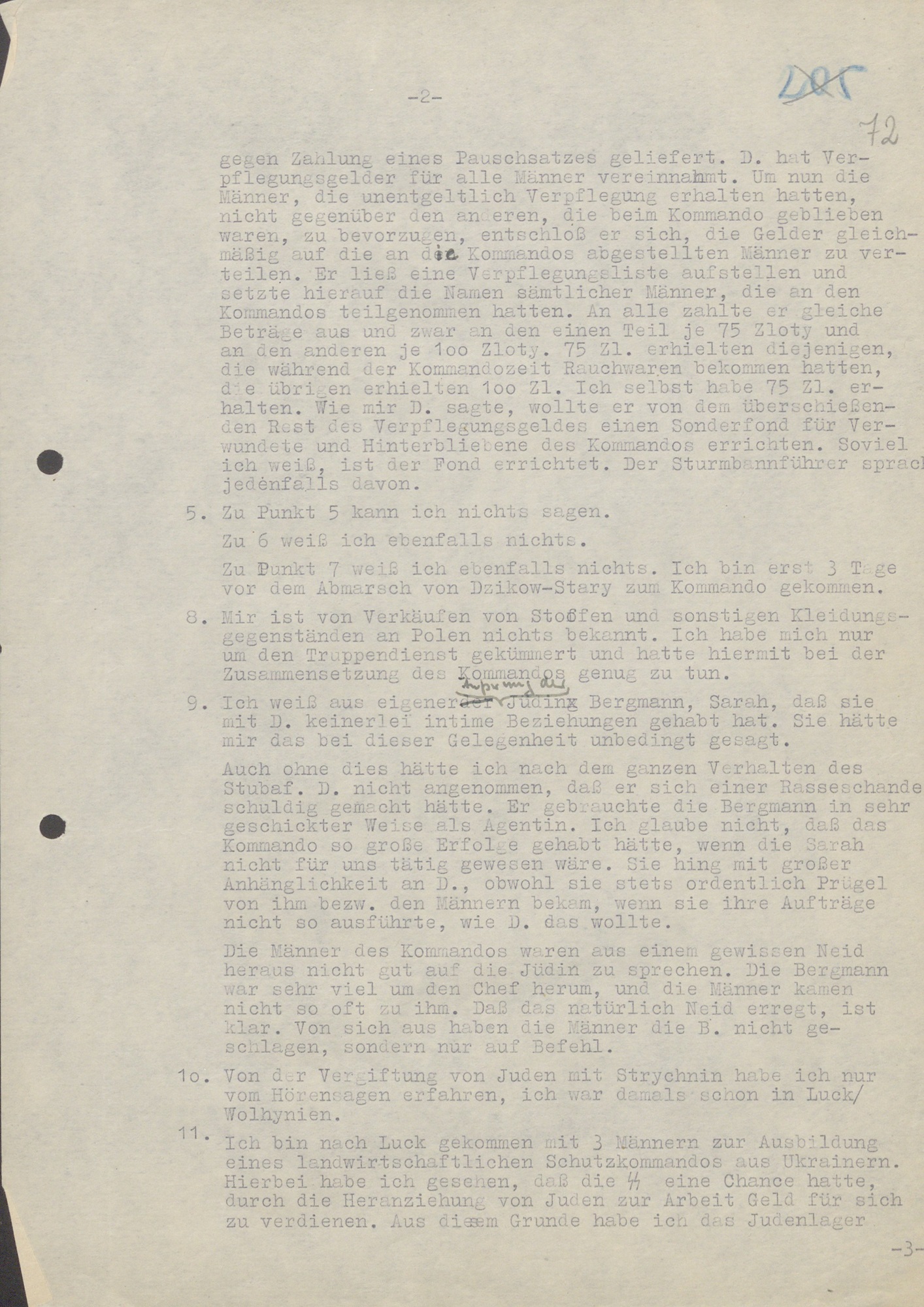

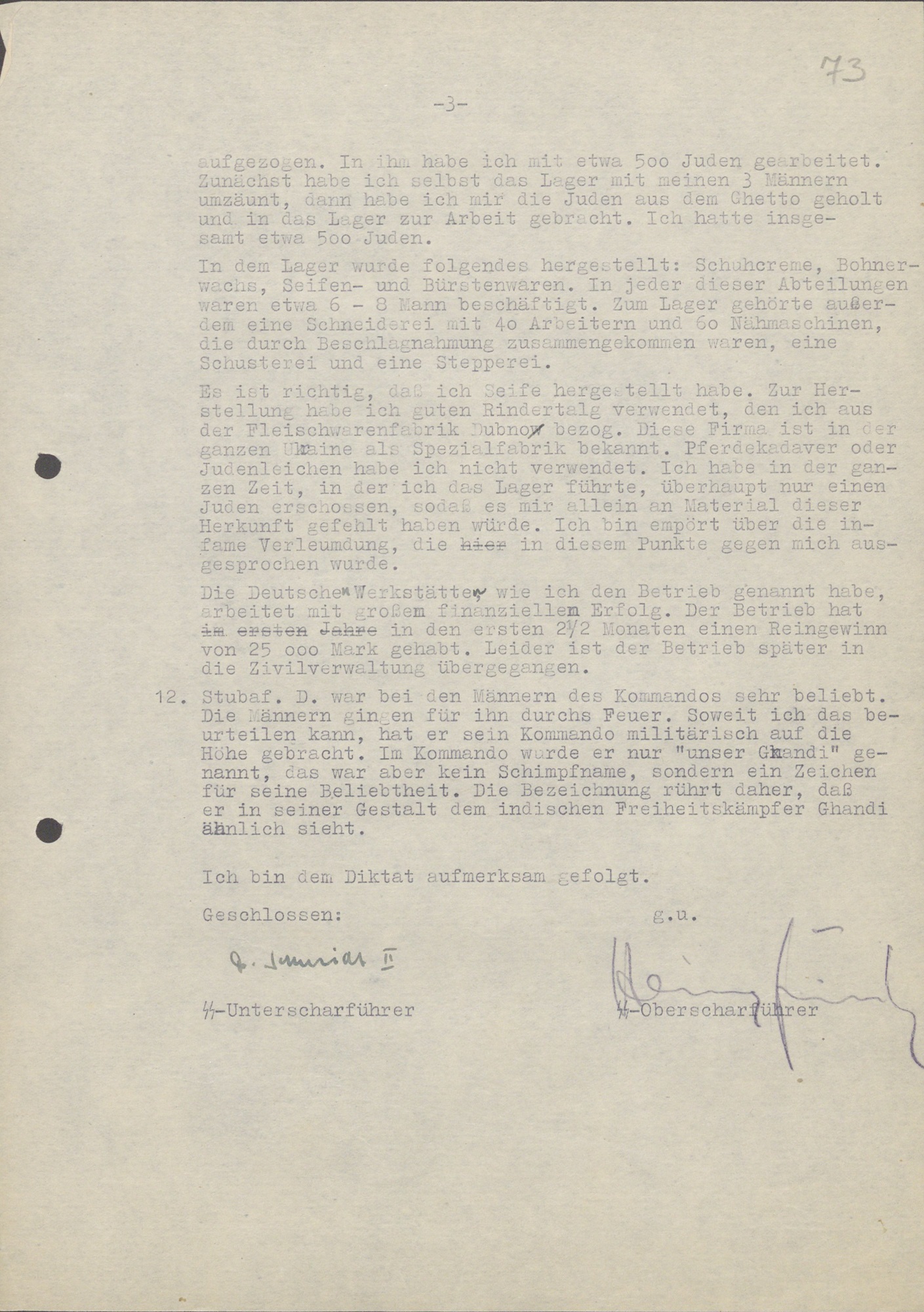

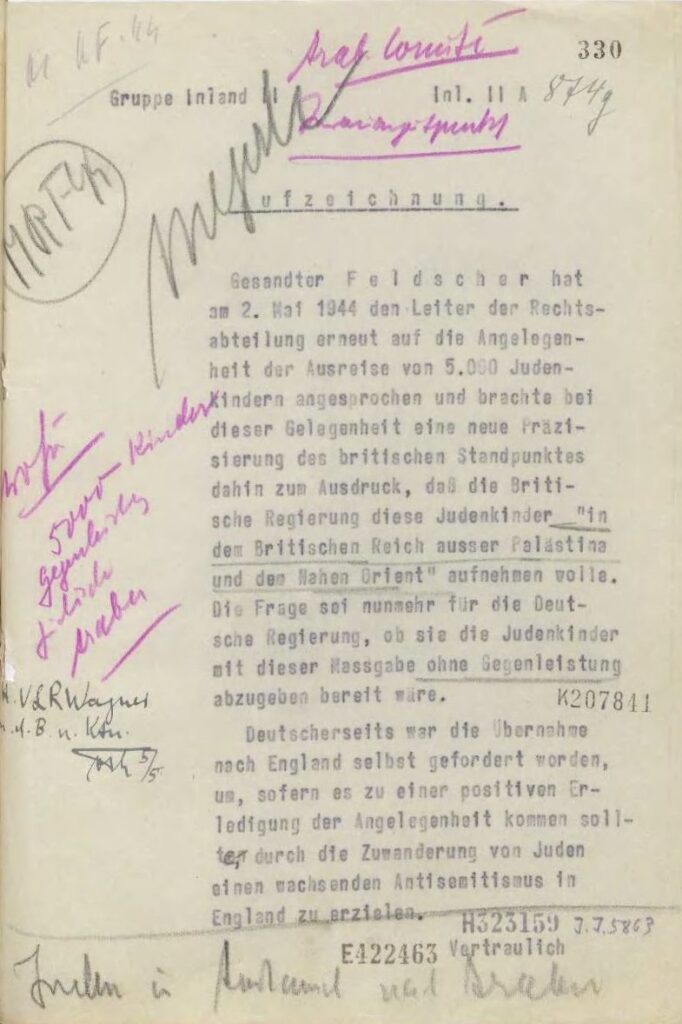

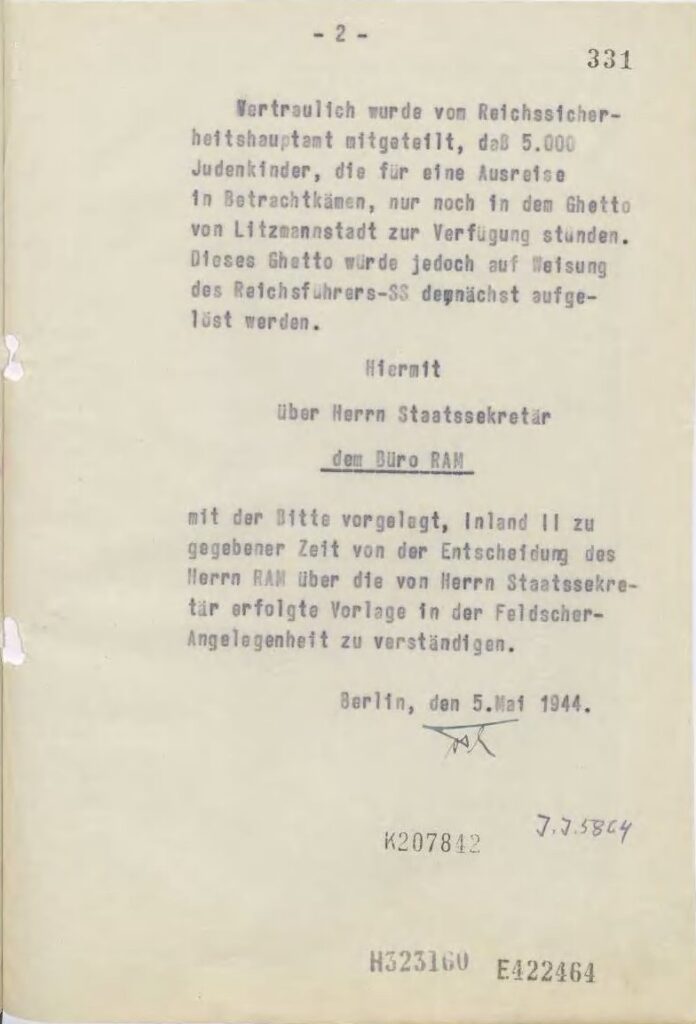

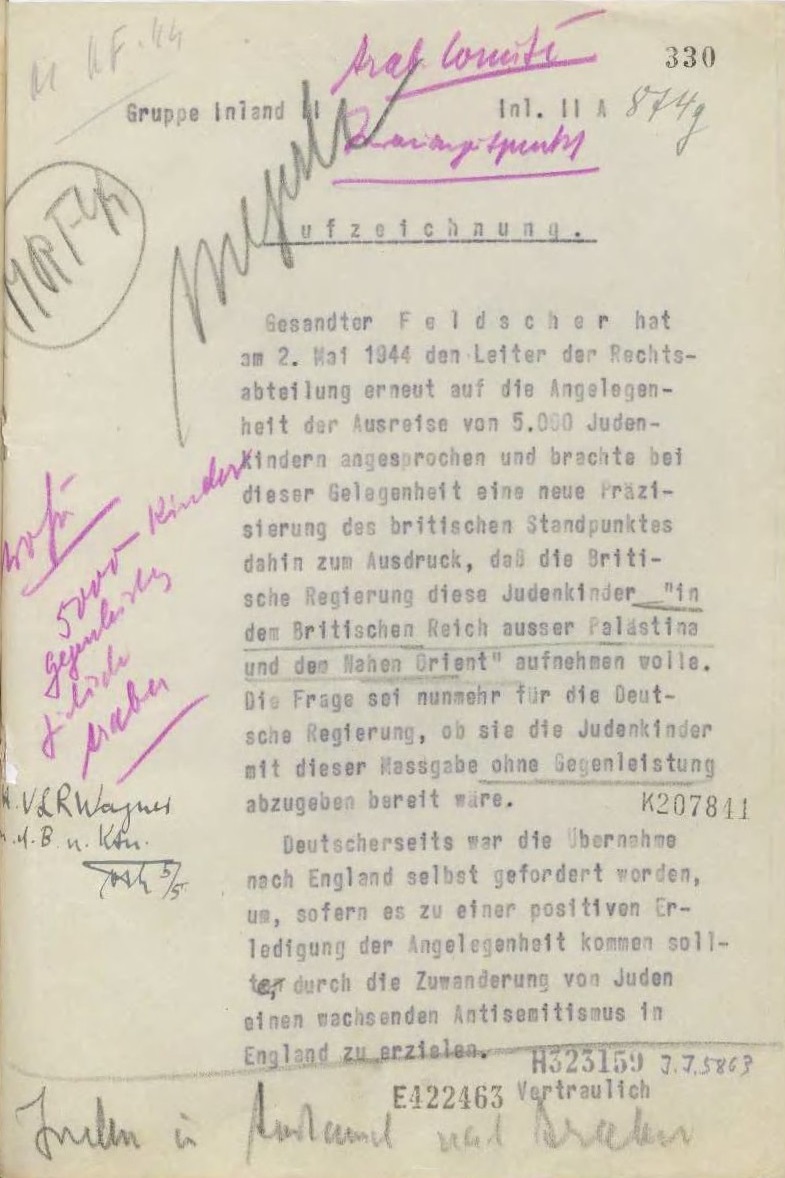

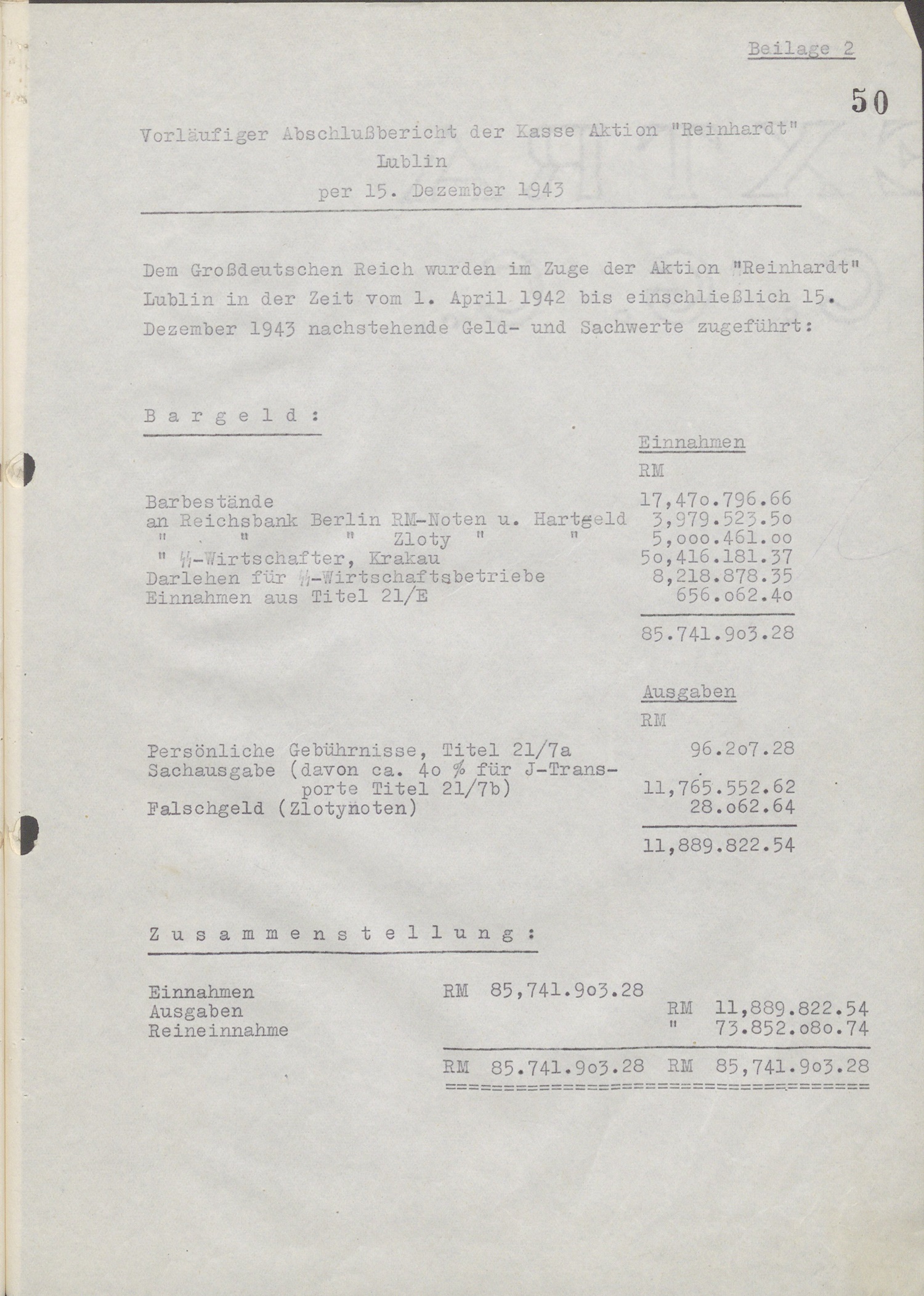

1941-12-18 Himmler’s Notes from Hitler’s HQ: “Jewish Question | To Be Exterminated as Partisans”

Introduction

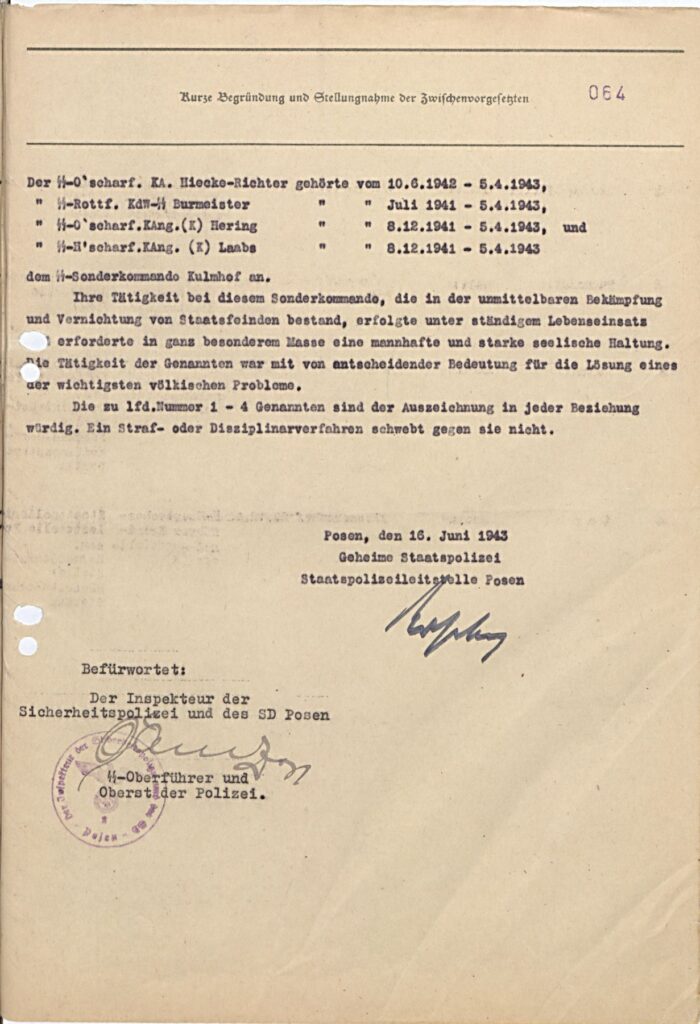

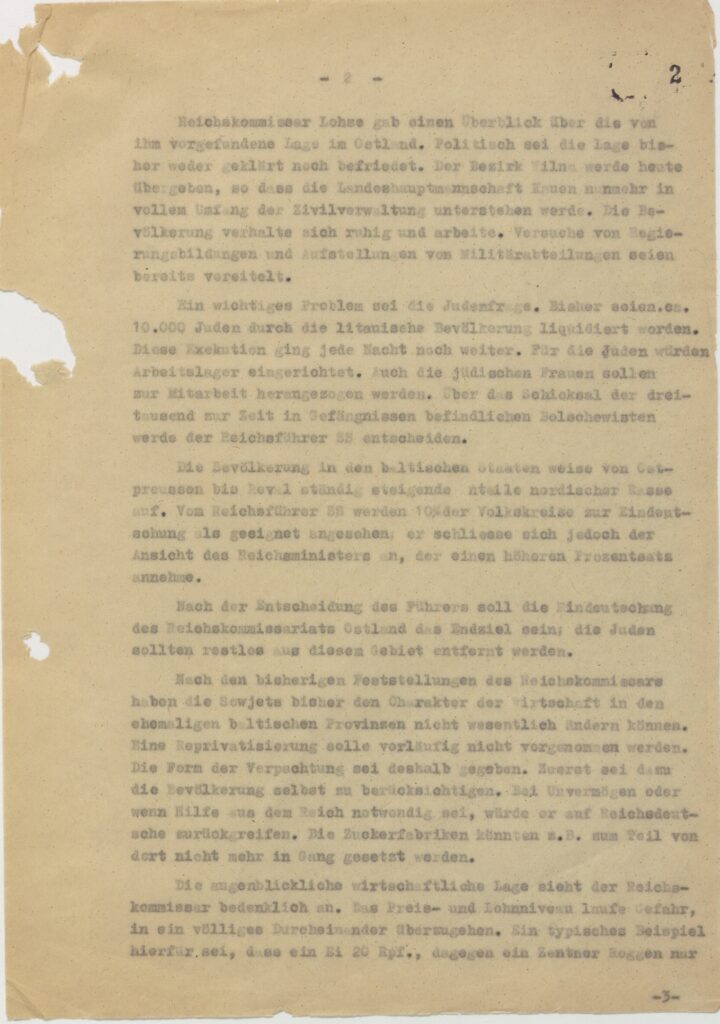

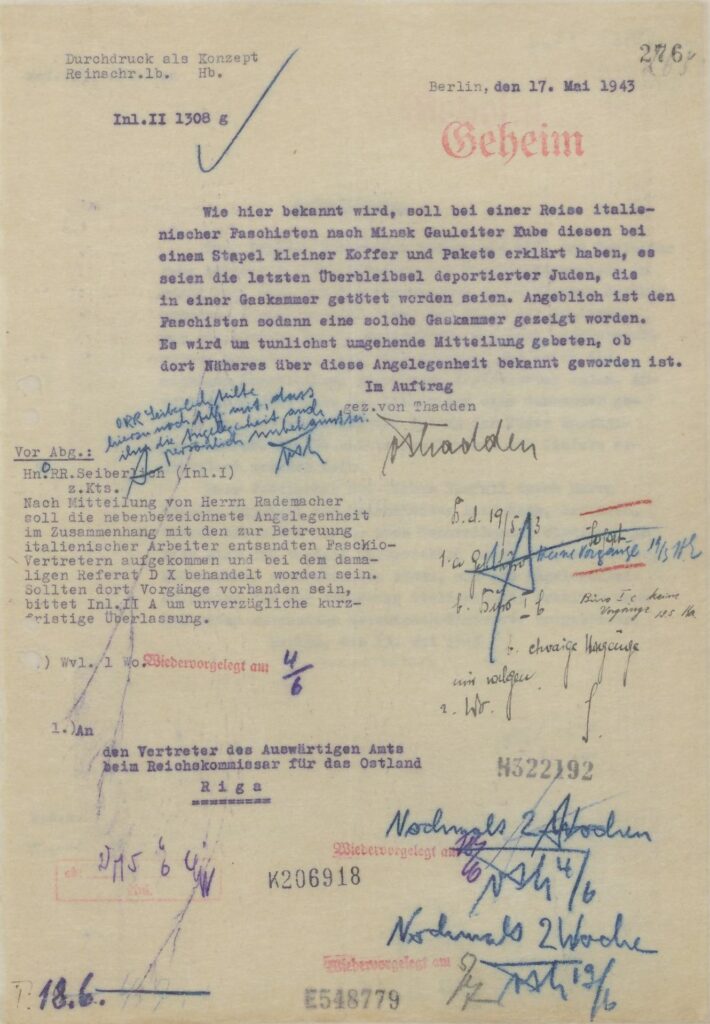

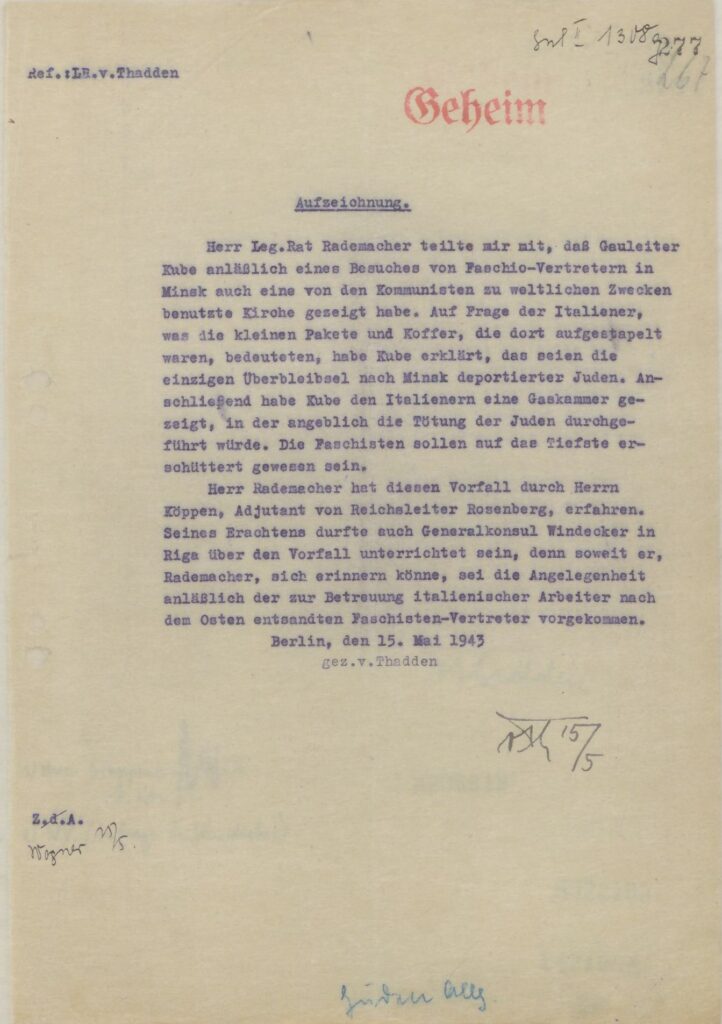

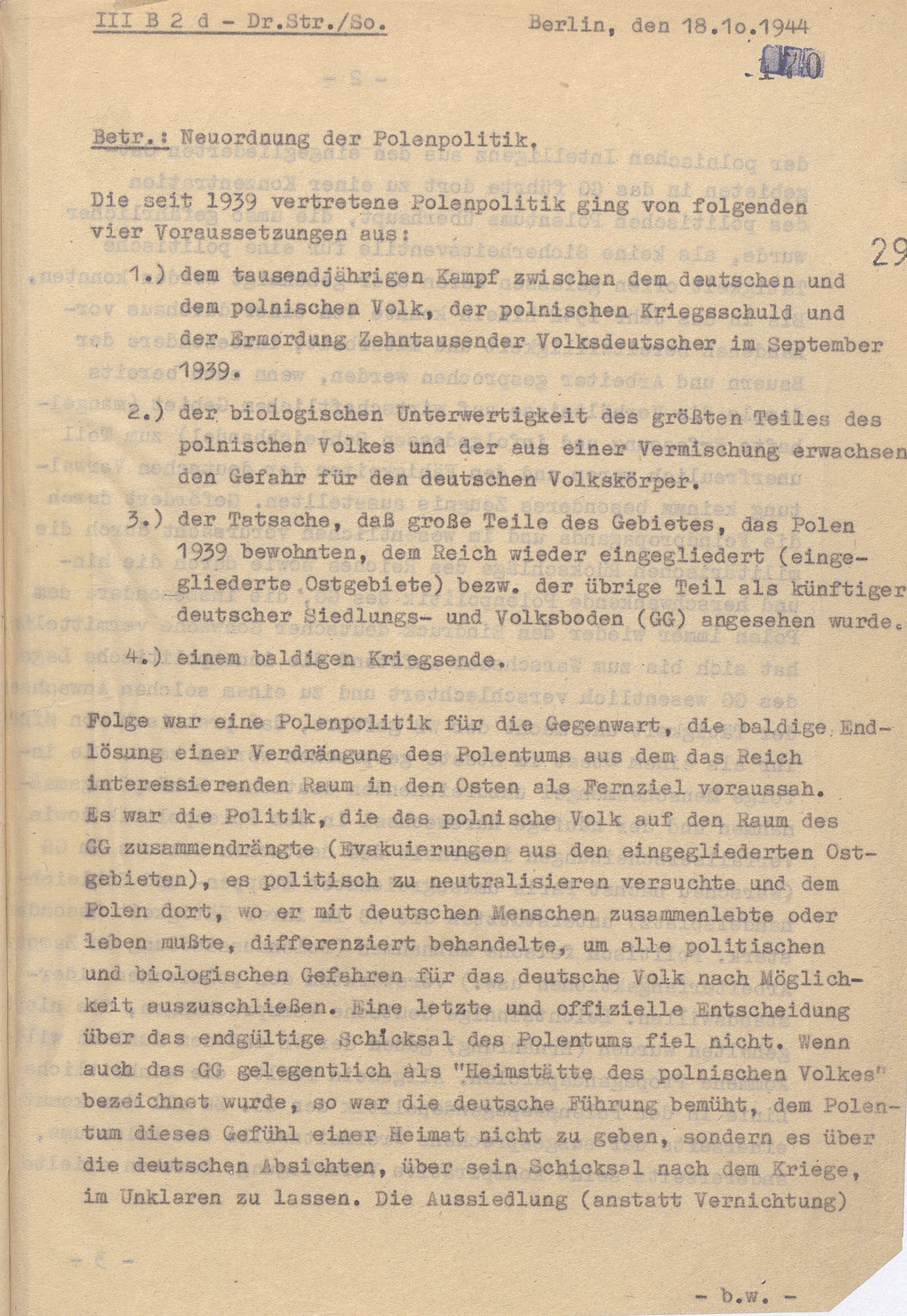

On December 18, 1941, Heinrich Himmler recorded a meeting with Adolf Hitler at the Führerhauptquartier (Wolfsschanze) in his Diensttagebuch (service diary). The brief entry reads: “Jewish Question. | To be exterminated as partisans.” The date marks a critical moment in the evolution of Nazi policy toward European Jews. Just days earlier, Hitler had announced the decision to physically exterminate the Jewish population within the Nazi sphere of influence. The phrase “To be exterminated as partisans” noted by Himmler appears to reflect an attempt to frame the genocide as a necessary wartime measure against alleged enemies and subversive elements. The general accusation was intended to justify the Jewish people’s collective destruction. 1

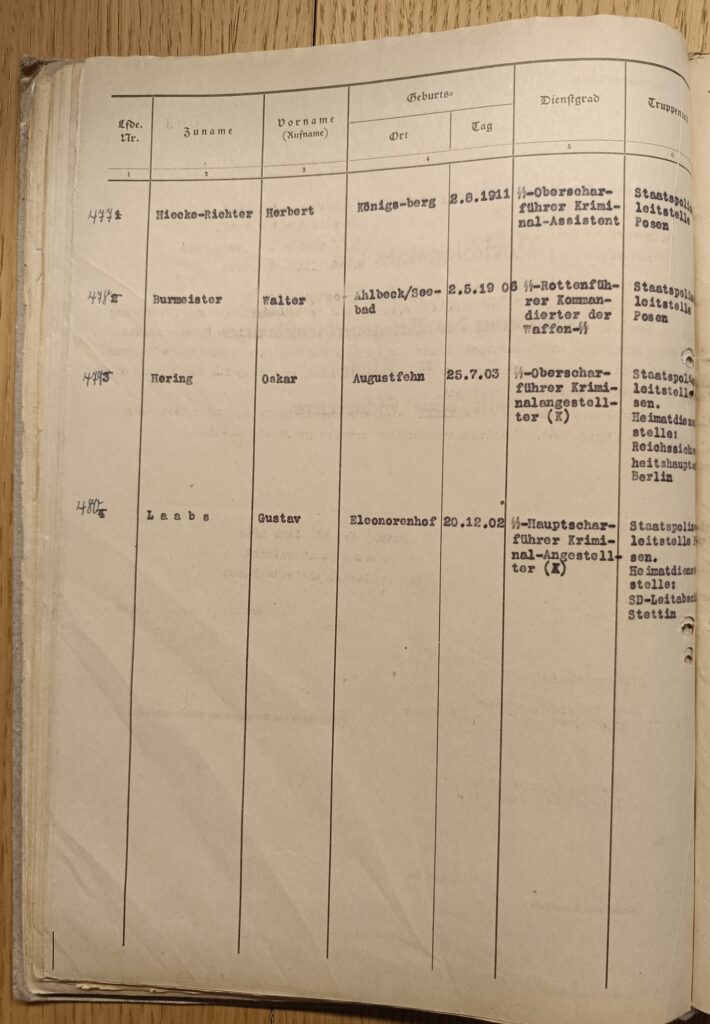

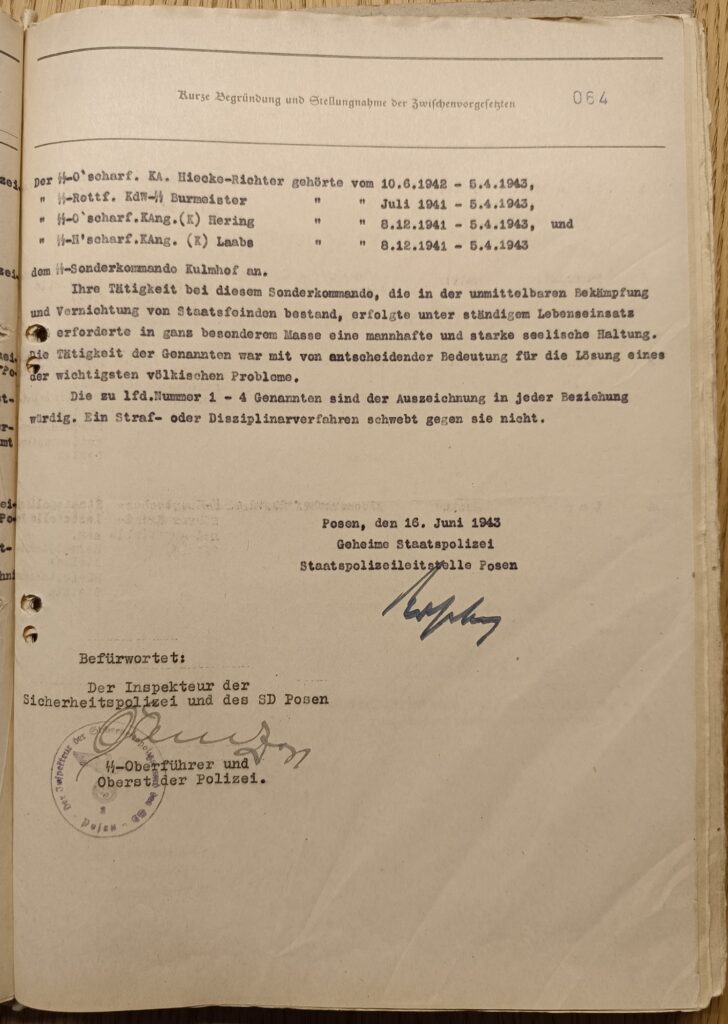

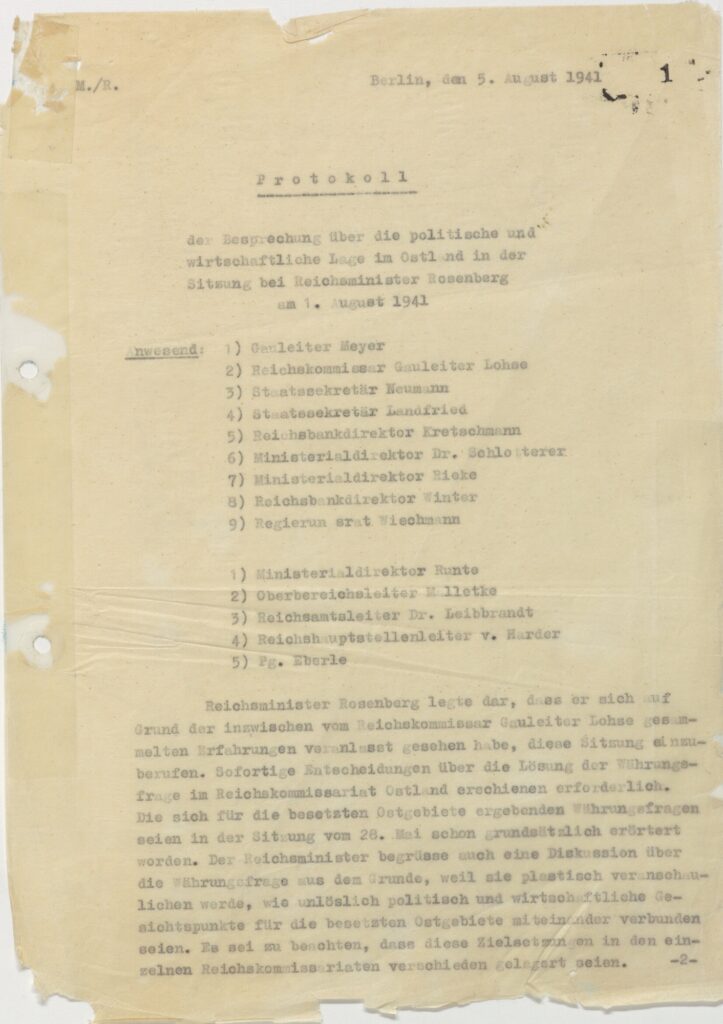

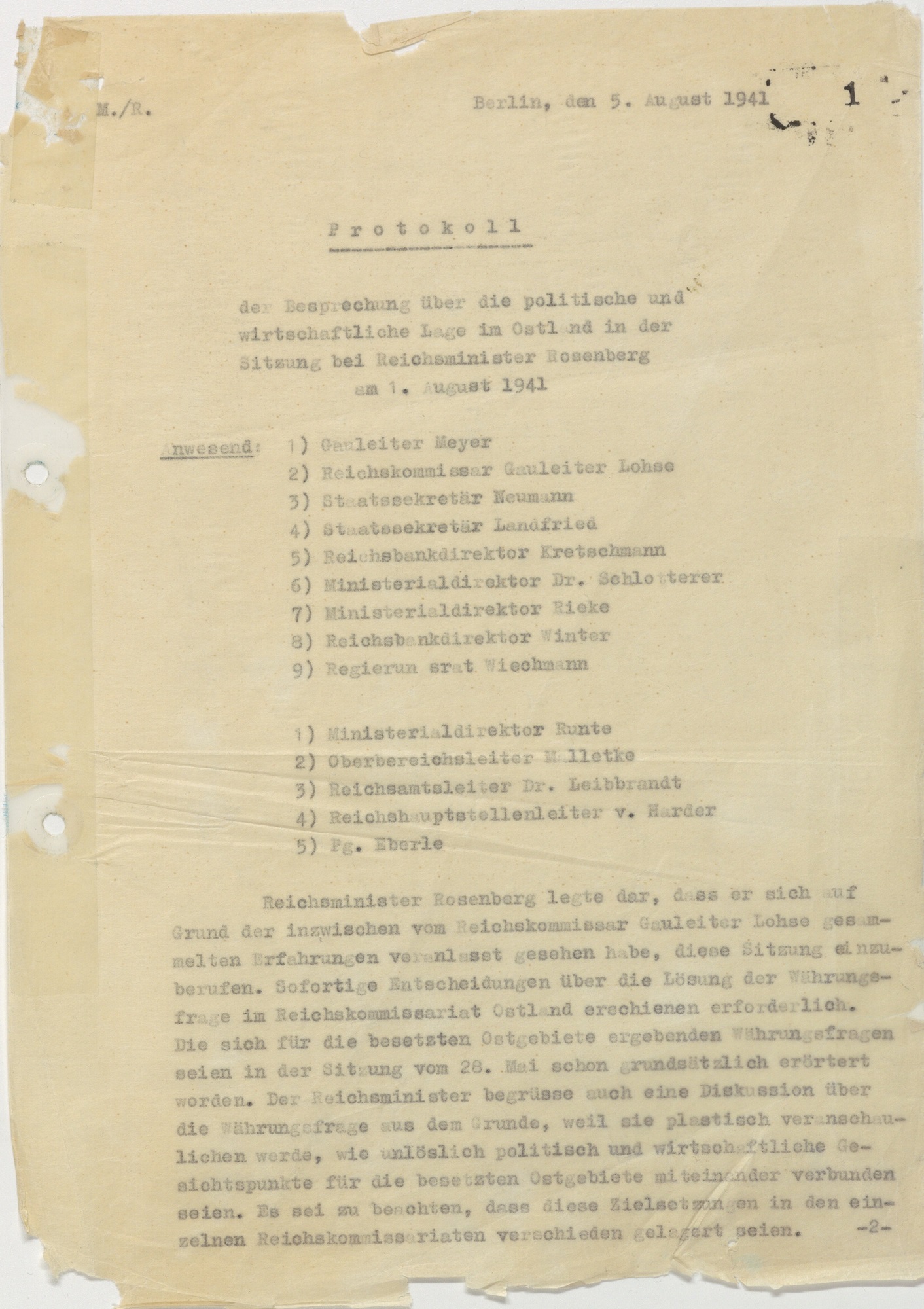

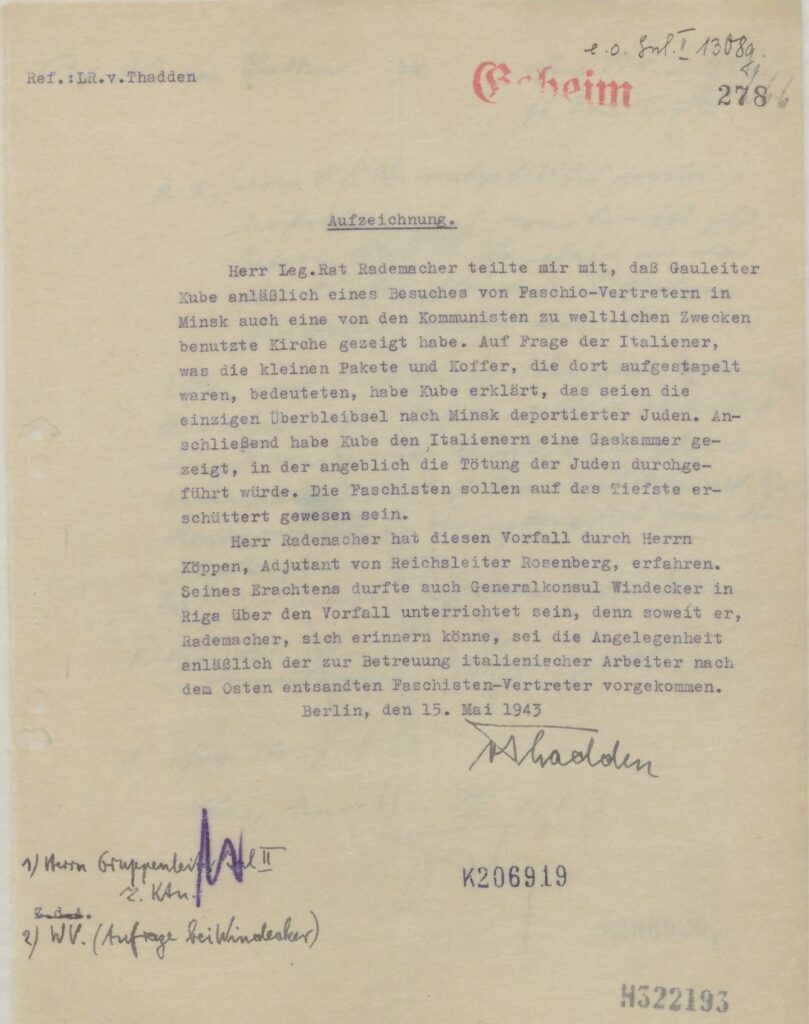

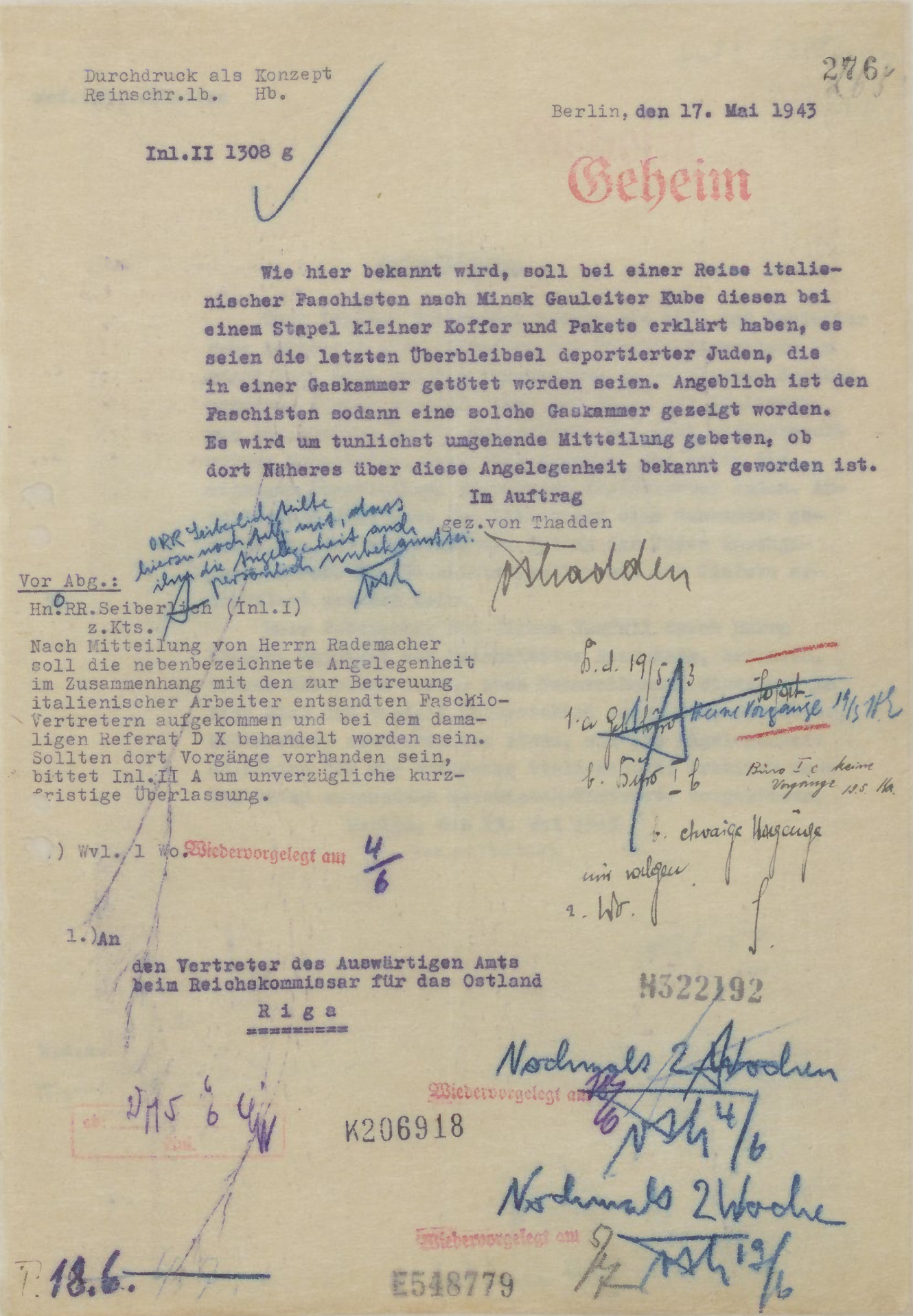

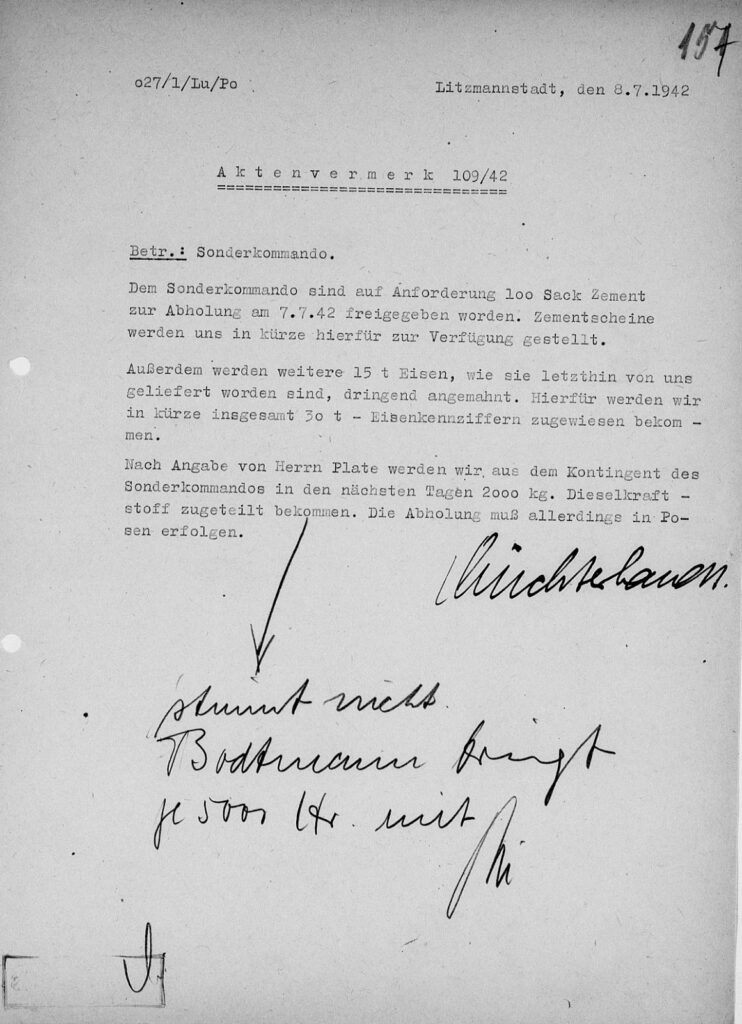

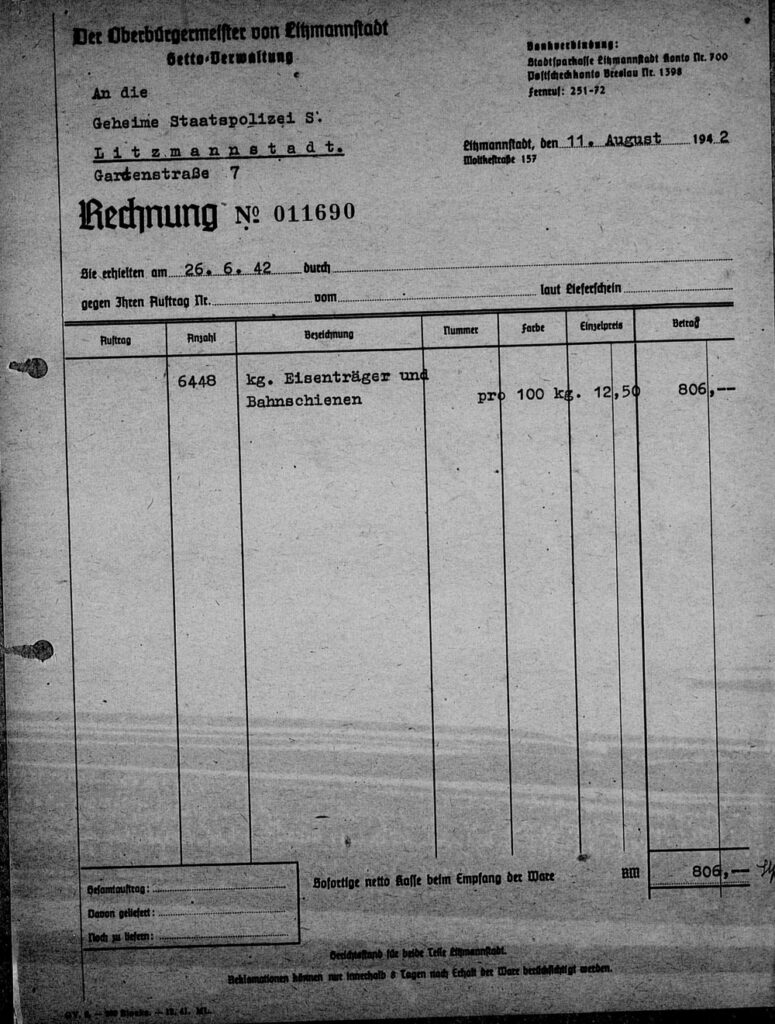

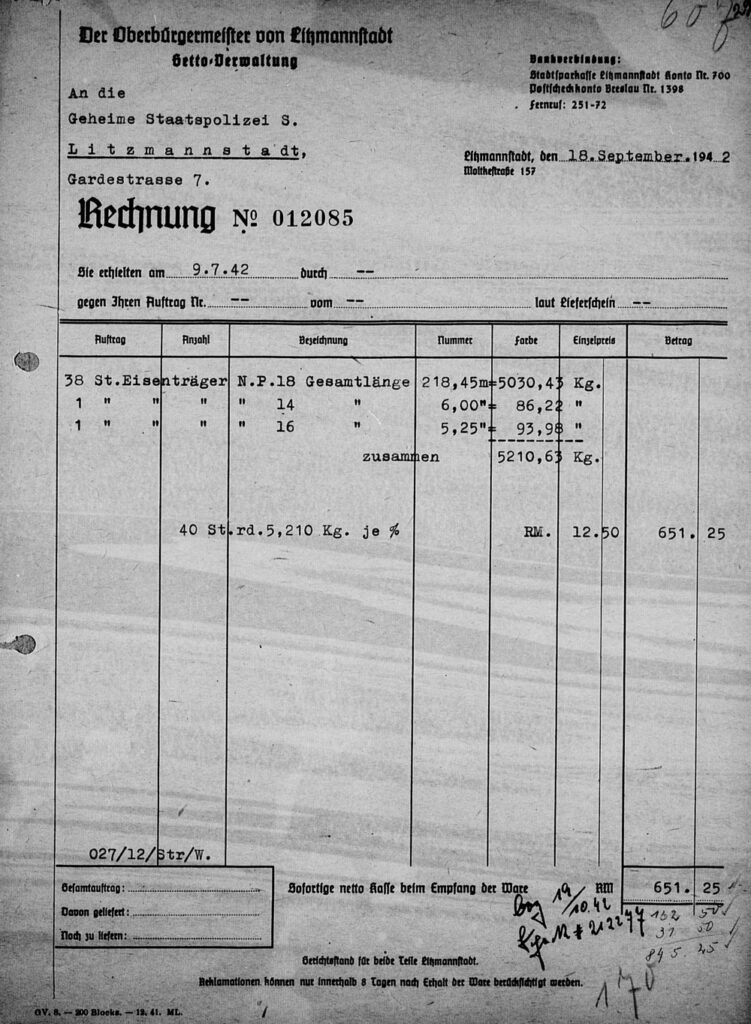

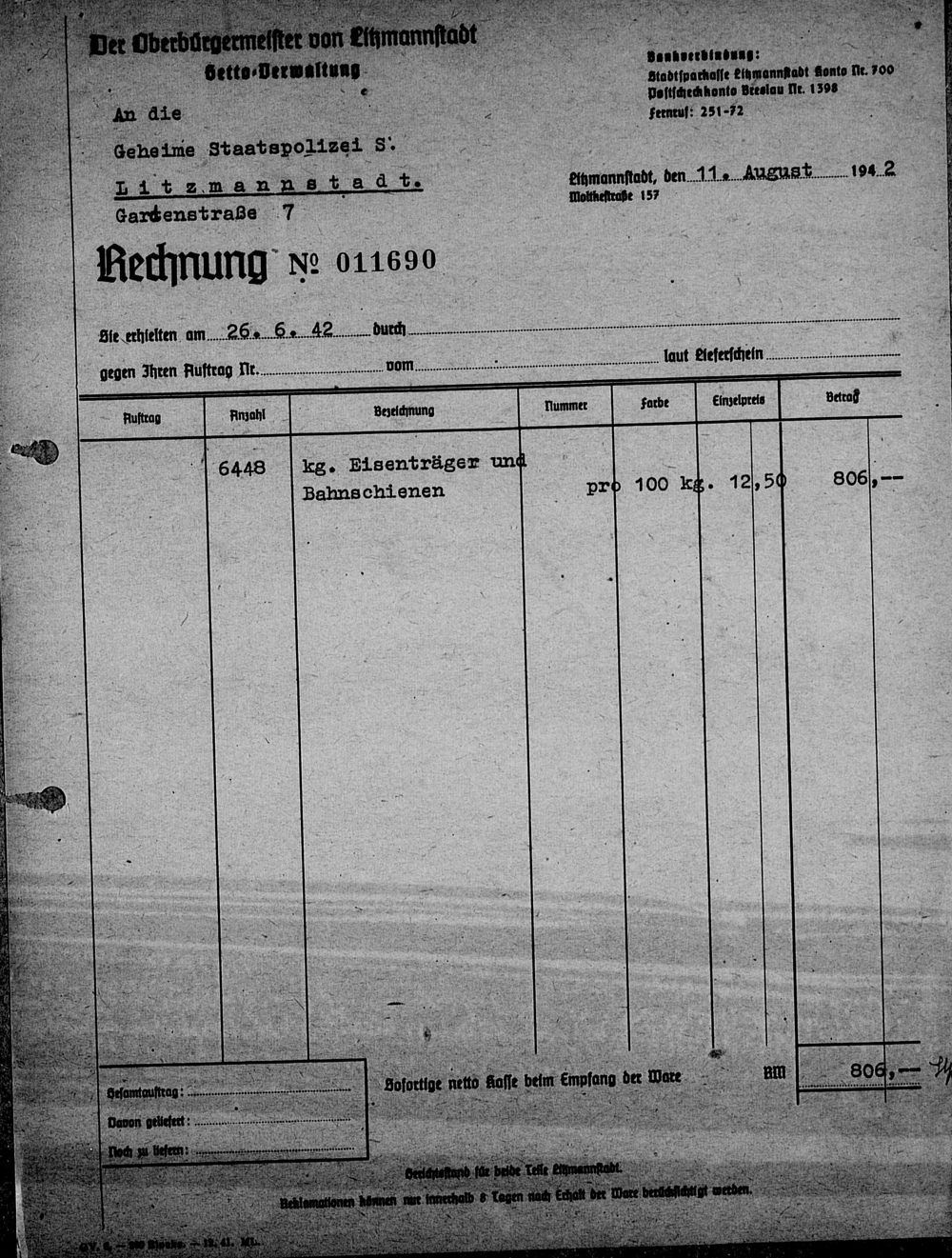

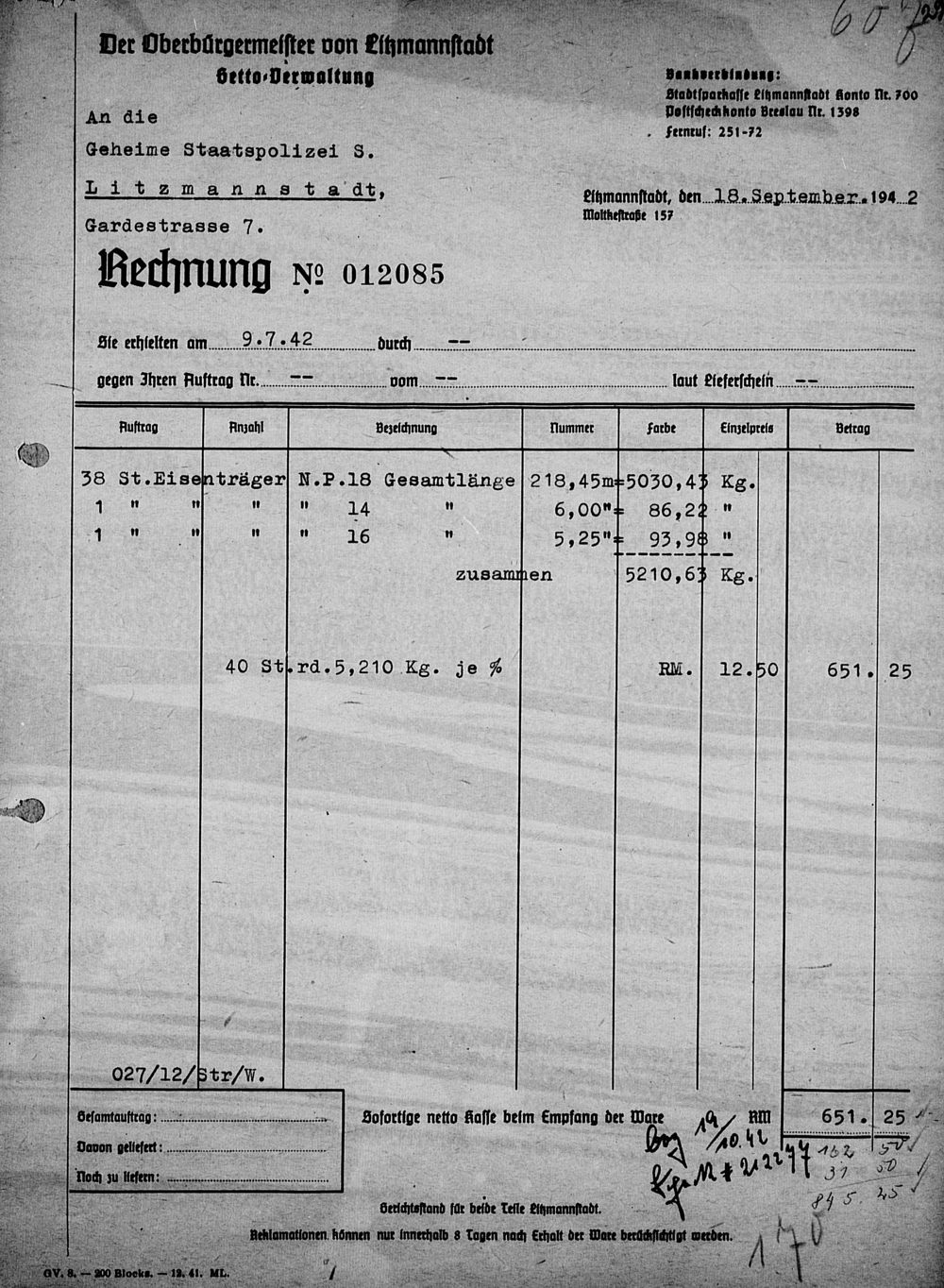

Documents

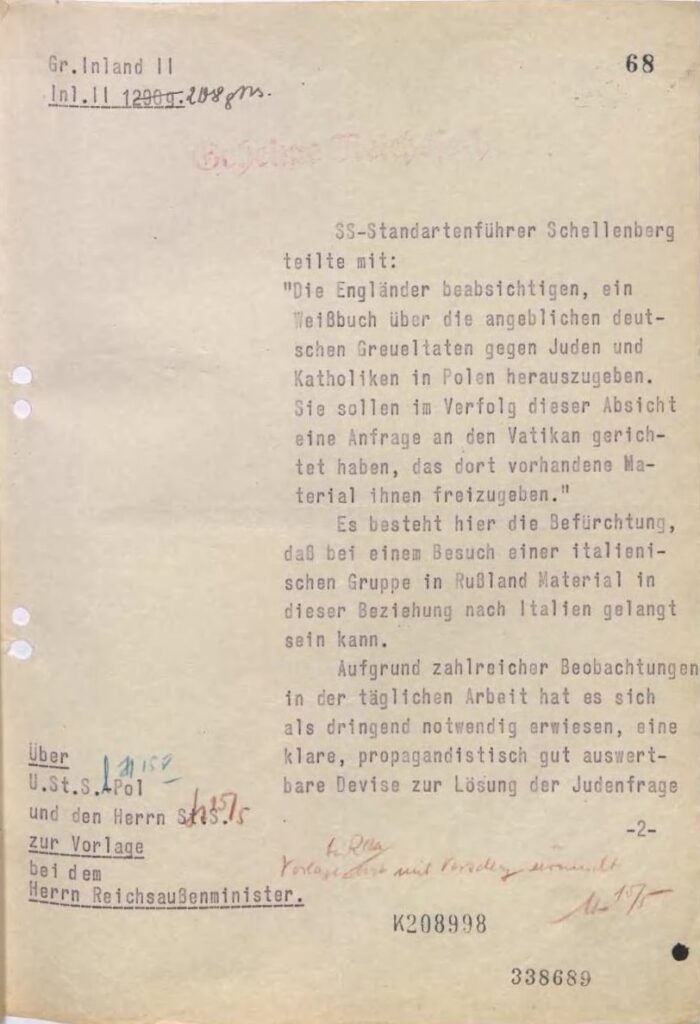

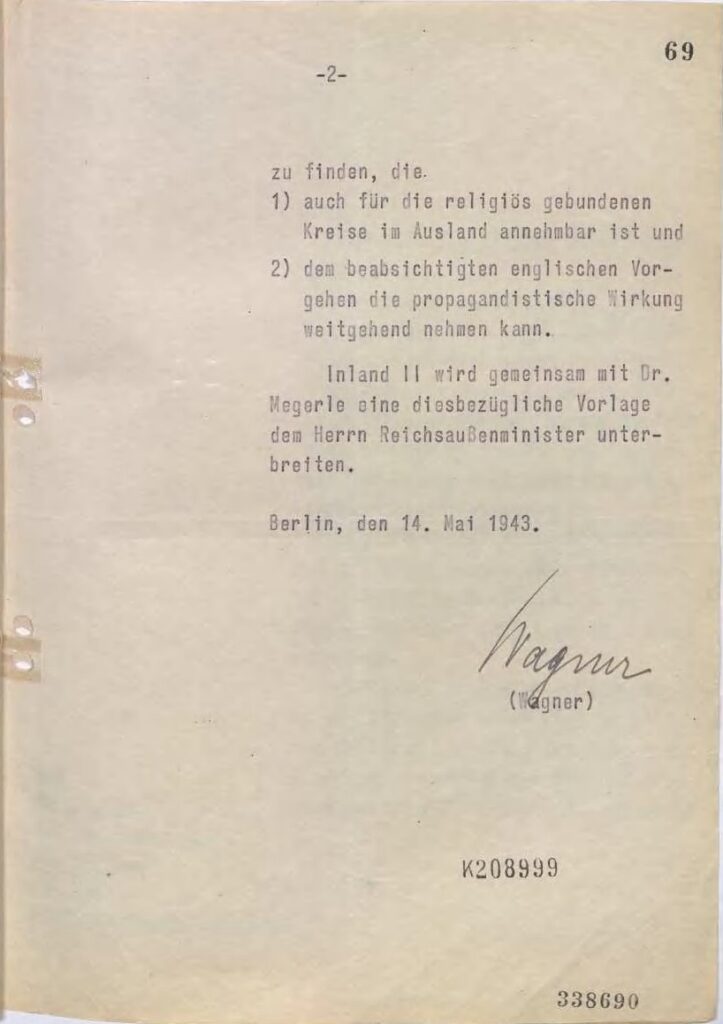

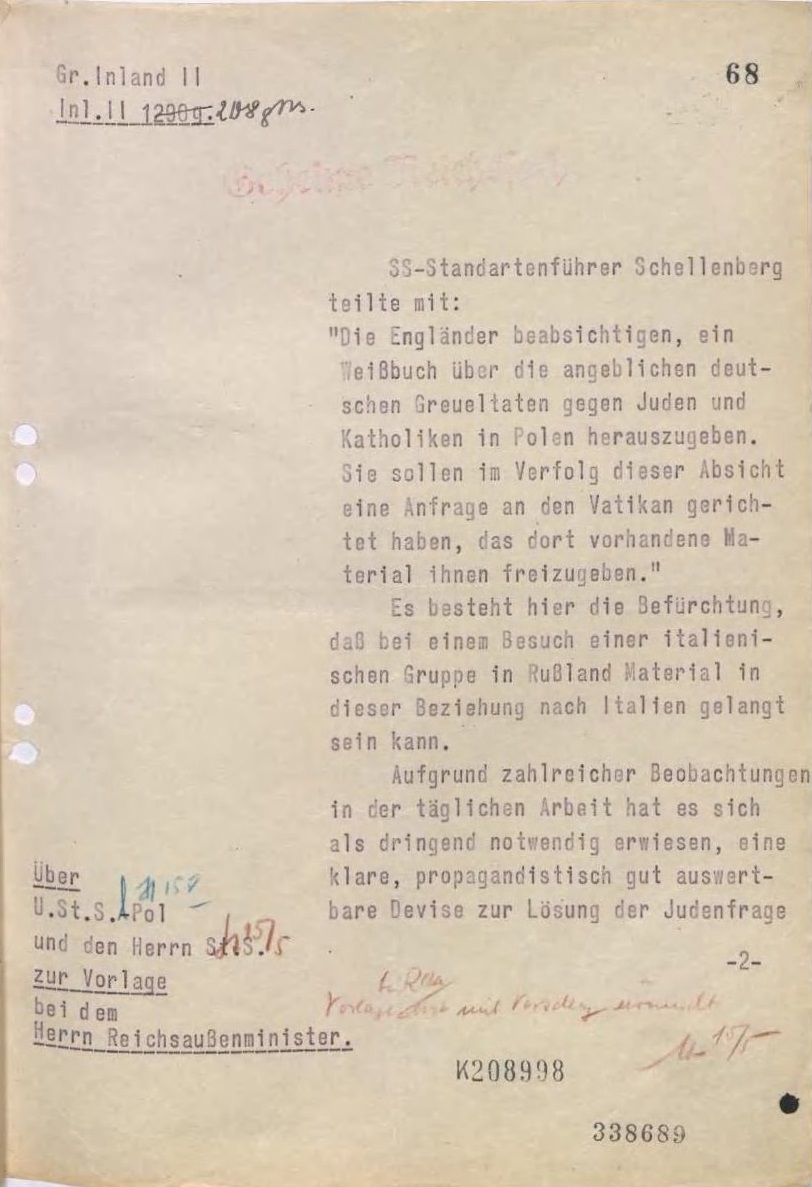

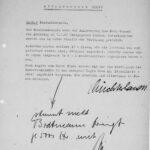

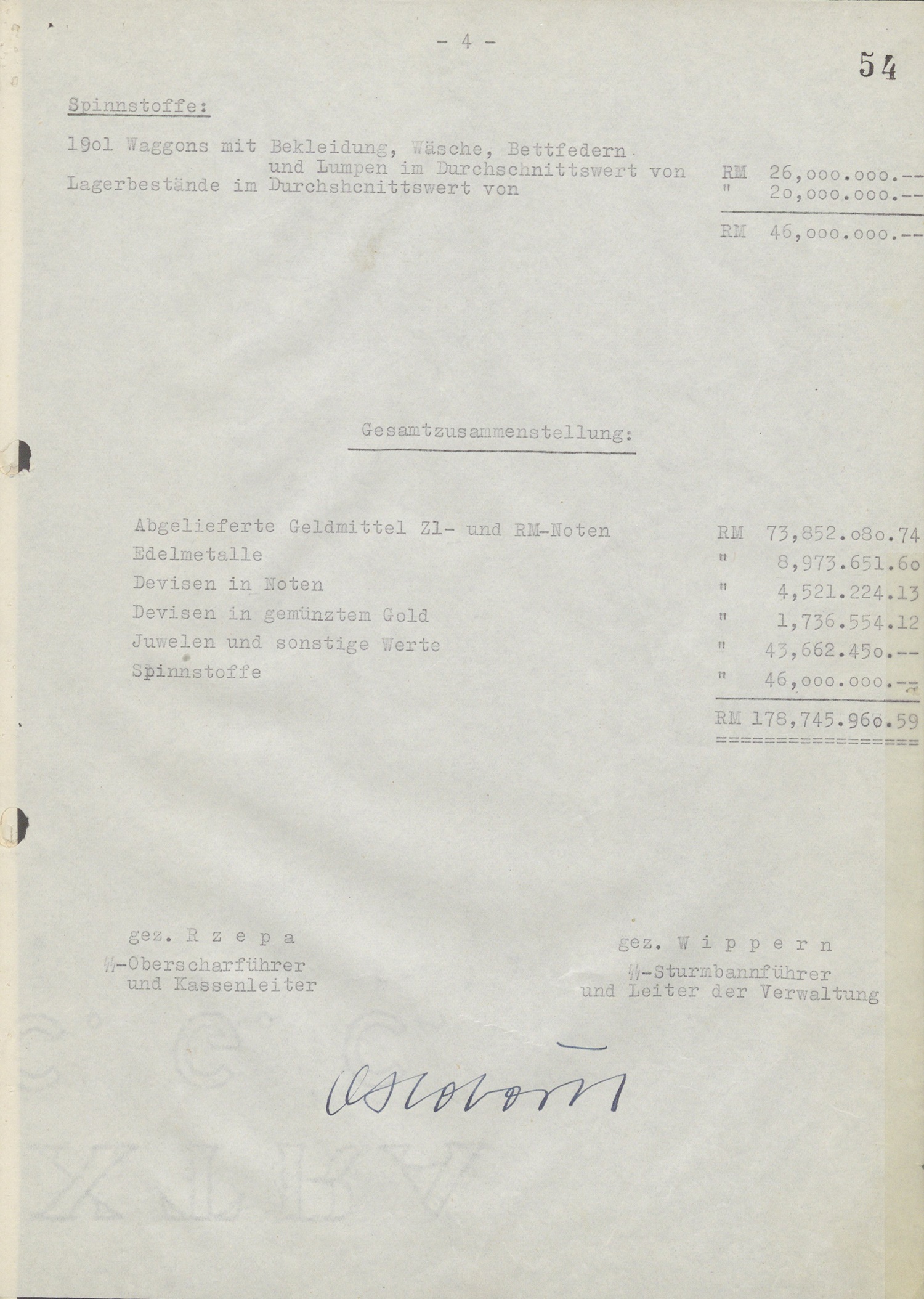

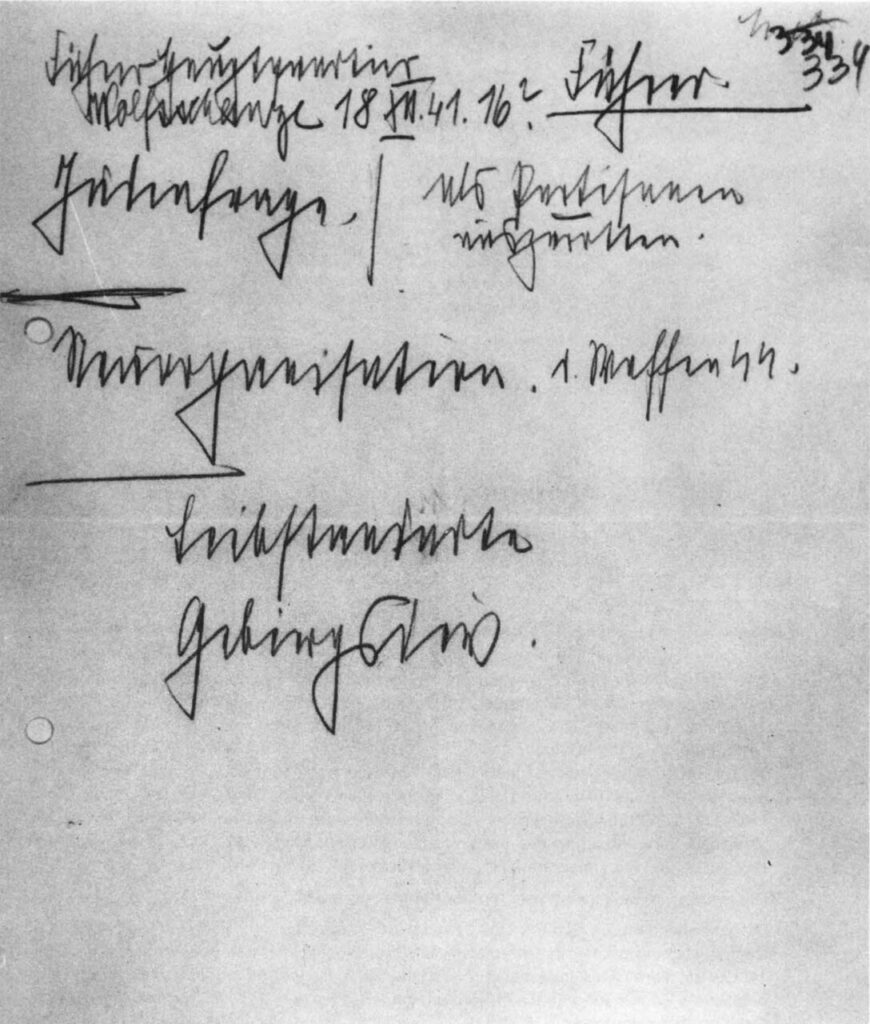

Führerhauptquartier

Wolfsschanze 18 XII.41. 16 h Führer

Judenfrage. | als Partisanen auszurotten

__________

Neuorganisation. i. Waffen SS.

__________

Leibstandarte

Gebirgsdiv.

Führer Headquarters

Wolf’s Lair, December 18, 1941, 4:00 PM Führer

Jewish Question. | To be exterminated as partisans.

___________

Reorganization in the Waffen SS.

__________

Leibstandarte

Mountain Division

Archivial reference:

Special Archives Moscow, 1372-5-23

Image reference:

Peter Witte, Der Dienstkalender Heinrich Himmlers 1941/42, Hamburg 1999, p. 293

- Christian Gerlach, The Extermination of the European Jews, p. 81 and 289. ↩︎