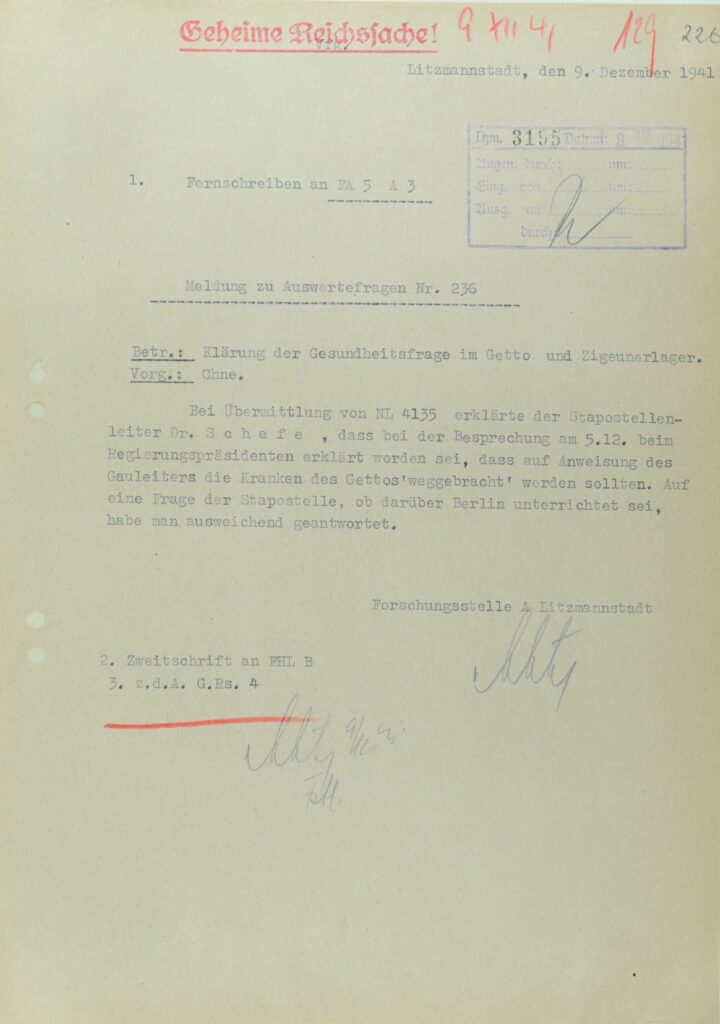

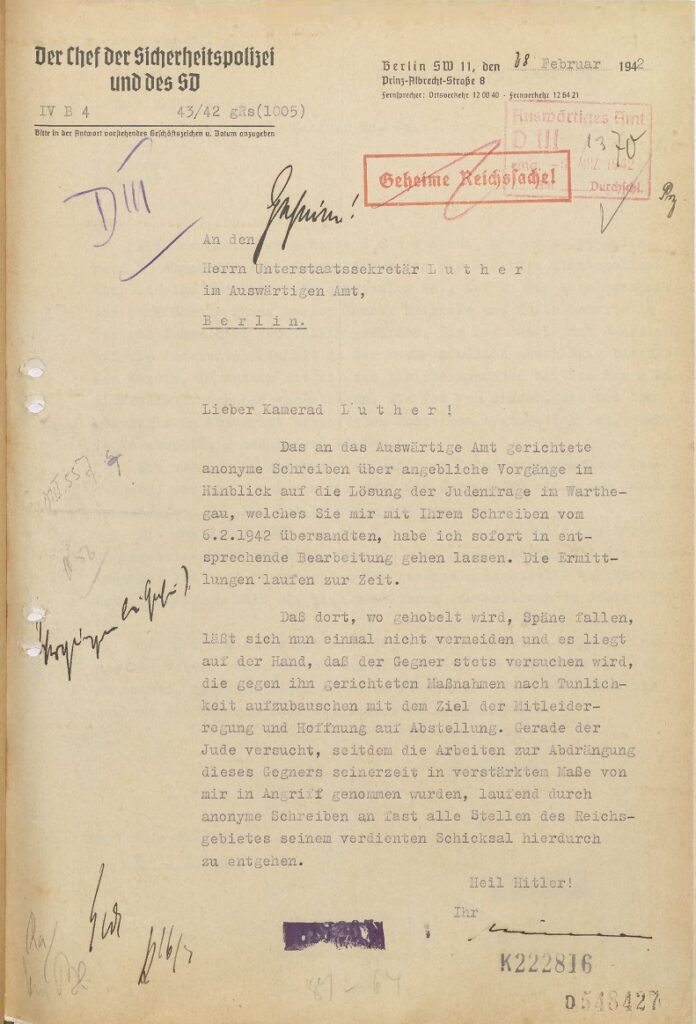

1941-12-09 Telex from Forschungsstelle A Litzmannstadt to Forschungsamt 5 A 3: “the sick from the ghetto should be “removed”. When the Stapo office asked whether Berlin had been informed about this, the response was evasive”

The telex, dated December 9, 1941, was sent from Forschungsstelle A Litzmannstadt to Forschungsamt 5 A 3, both of which were components of Hermann Göring’s Secret Service Forschungsamt of the Reich Ministry of Aviation. The message from the Litzmannstadt branch mentions a conversation involving Robert Schefe, the head of the local Stapo office that “by order of the Gauleiter, the sick from the ghetto should be ‘removed’.” Furthermore, when questions were raised about whether central authorities in Berlin had been informed of this decision, the response of the Stapo “was evasive”.

The term “removed” implies the extermination of the sick in Kulmhof extermination camp, where the operation was ramped-up at the time. The evasive answer about informing Berlin suggest a possible attempt to manage such operations discretely or independently at the local level, indicating the decentralized nature of some Nazi policies.