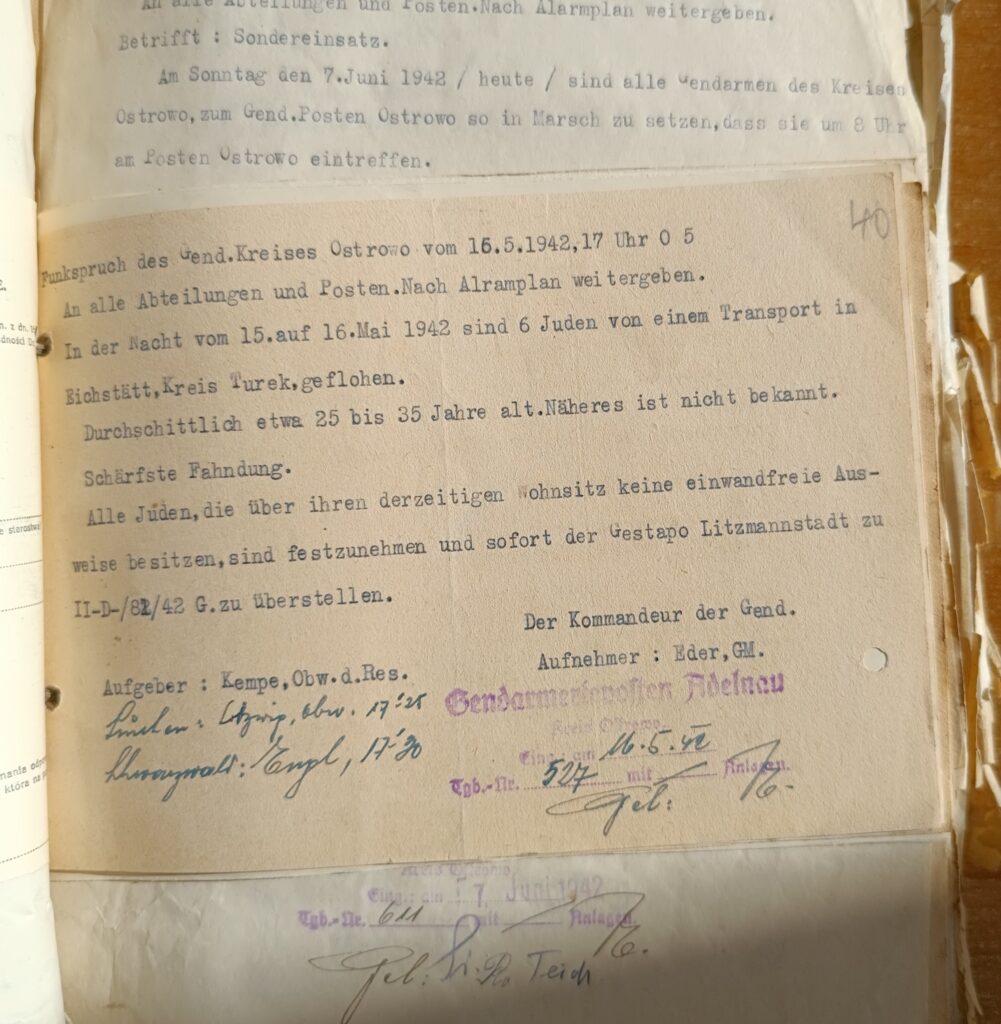

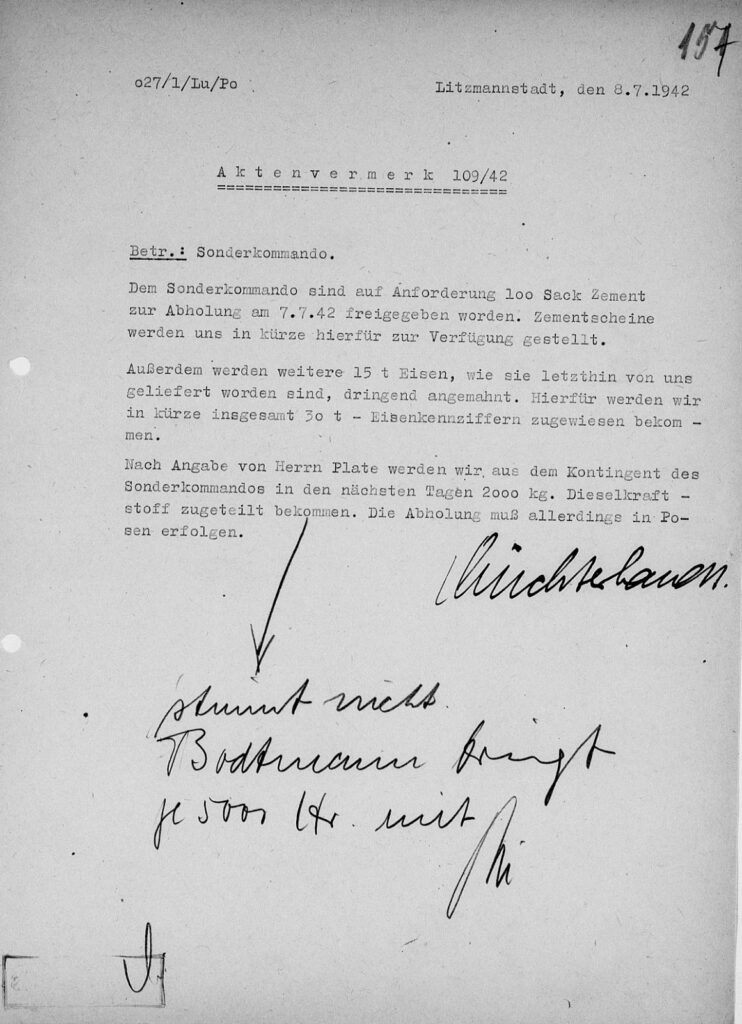

1942-05-16 Police Radio Message Reporting Escape of Six Jews Near Kulmhof (Chełmno) Extermination Camp

Radio message from the Gendarmerie District Ostrowo to the Gendarmerie post in Adelnau, dated May 16, 1942. The message reported that “six Jews escaped from a transport in Eichstätt”. Eichstätt, known in Polish as Dąbie, is the closest town to Kulmhof (Chełmno) extermination camp, approximately 6 km southeast of Chełmno nad Nerem.